Bon anniversaire to two literary legands

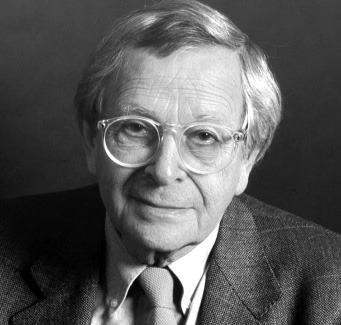

September 19th marked two major birthdays for twentieth-century (and beyond) letters—and lucky are we to share in their celebration. The celebrated figures in question couldn’t be more distinct—Roger Grenier, a writer and champion of fine arts and culture, a former student of Gaston Bachelard, whose editorial finesse helped shape French publisher Gallimard into a global force, once described by the Guardian as possessing, “the best backlist in the world”; and Mike Royko (1932–97), Pulitzer Prize–winning Chicago newspaper columnist and author whose local-boy-does-good commentaries and investigative journalism became the mouthpiece of the city he called home.

September 19th marked two major birthdays for twentieth-century (and beyond) letters—and lucky are we to share in their celebration. The celebrated figures in question couldn’t be more distinct—Roger Grenier, a writer and champion of fine arts and culture, a former student of Gaston Bachelard, whose editorial finesse helped shape French publisher Gallimard into a global force, once described by the Guardian as possessing, “the best backlist in the world”; and Mike Royko (1932–97), Pulitzer Prize–winning Chicago newspaper columnist and author whose local-boy-does-good commentaries and investigative journalism became the mouthpiece of the city he called home.

Grenier turned 93 on Wednesday, the same day his new collection of short stories Brefs récits pour une longue histoire was published in his native France. The author of more than thirty works of fiction, essay collections, and prose, Grenier is perhaps best known in the United States for the iconic vignettes on offer in The Difficulty of Being a Dog, translated by Alice Kaplan and published by the University of Chicago Press in 2000. This spring will usher in the publication of Grenier’s A Box of Photographs, and with it, his candid reflections on the history of photography. The depth and breadth of his output should be no surprise to those familiar with his work, among them the Académie française, who awarded Grenier the Grand prix de l’Académie française (1985) for his collected works.

An excerpt from The Difficulty of Being a Dog follows below. Read more here.

For years I used to walk Ulysses in our neighborhood, so we ended up knowing a lot of people. Dogs are like Emmanuel Kant, who always wanted to take the same walk. The less it changes, the happier they are. Leaving the house, we would turn left. Unless, inadvertently, I uttered the word “Tuileries,” in which case there was nothing to be done; Ulysses would turn right and I had to follow him. We would march across the rue de Varenne under the surveillance of the policemen who guard the intersection in front of the Matignon, the official residence of the prime minister. These security police, many of them from rural areas, would compliment the Saint-Germain pointer on his beauty or ask me about his hunting skills. Depending on the day, I would lie or tell the truth, the truth being that he didn’t hunt.

A little farther on, Dora, the big black dog that guarded the Catholic Rescue Mission, would have smelled our arrival. She would start to cry with emotion, with desire. She would thrust her muzzle through the bars of the gate to kiss her beloved. Dora, the black sinner in a pious community of bishops, priests, saintly women.

The next house belonged to the writer Romain Gary. On our first outing at 7:30 in the morning, we would often meet him strolling down the street, going to buy the newspaper or to have a cup of coffee across the way. Gary said that the rue du Bac was his country. Tartar, Jew, Russian, Pole: he was a mix of so many things that he had no desire to be a citizen of the world, a European, or even a Frenchman. What he required was membership in a tiny province or someplace even smaller. Hence the rue du Bac. “Come here, you jerk,” he would say to Ulysses, who would advance immediately, stretch his hind legs, and rub up against him.

One day in September 1980, we met Gary near the front of his building. As usual he said, “Come here, you jerk!” We approached. I said to Romain: “I’m afraid this is the last time you’ll see Ulysses. He’s going to be put to sleep.”

Romain let out a violent sob and hid in his entryway.

Ulysses died September 23; Gary died December 2.

In one year, Gary’s former wife (the actress Jean Seberg), Gary himself, and Ulysses all died, and the street was empty. I might as well speak of all three in the same breath, since we loved one another.

***

Columnist Mike Royko would have turned 80 earlier this week—at the height of his career, his work for the Chicago Daily News, Chicago Sun-Times, and Chicago Tribune was syndicated in more than 600 newspapers across the country. His place among the citizen-journalists that defined twentieth-century Chicago is unparalleled at best, and irreplaceable at worst. An Air Force veteran who grew up the son of Polish–Ukrainian immigrants, Royko never turned his back on his blue-collar background, which inflected the series of fictitious personas central to his commentaries (Slats Grobnik, the most famous among them). Perhaps most widely known for Boss, his 1971 unauthorized biography of Richard J. Daley, Royko is also the author of several other works, among them One More Time: The Best of Mike Royko; For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko; and Early Royko: Up Against It in Chicago. In 2010, Royko’s son David added another selection to all things Rokyo, editing Royko in Love: Mike’s Letters to Carol, which chronicled the then-young airman’s fledgling affections for his childhood sweetheart and first wife, Carol Duckman.

Columnist Mike Royko would have turned 80 earlier this week—at the height of his career, his work for the Chicago Daily News, Chicago Sun-Times, and Chicago Tribune was syndicated in more than 600 newspapers across the country. His place among the citizen-journalists that defined twentieth-century Chicago is unparalleled at best, and irreplaceable at worst. An Air Force veteran who grew up the son of Polish–Ukrainian immigrants, Royko never turned his back on his blue-collar background, which inflected the series of fictitious personas central to his commentaries (Slats Grobnik, the most famous among them). Perhaps most widely known for Boss, his 1971 unauthorized biography of Richard J. Daley, Royko is also the author of several other works, among them One More Time: The Best of Mike Royko; For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko; and Early Royko: Up Against It in Chicago. In 2010, Royko’s son David added another selection to all things Rokyo, editing Royko in Love: Mike’s Letters to Carol, which chronicled the then-young airman’s fledgling affections for his childhood sweetheart and first wife, Carol Duckman.

Below follows a prototypical column Royko wrote on October 15, 1972, the day Jackie Robinson died. To read more, go here and here.

***

“Jackie’s Debut a Unique Day”

All that Saturday, the wise men of the neighborhood, who sat in chairs on the sidewalk outside the tavern, had talked about what it would do to baseball.

I hung around and listened because baseball was about the most important thing in the world, and if anything was going to ruin it, I was worried.

Most of the things they said, I didn’t understand, although it all sounded terrible. But could one man bring such ruin?

They said he could and would. And the next day he was going to be in Wrigley Field for the first time, on the same diamond as Hack, Nicholson, Cavarretta, Schmitz, Pafko, and all my other idols.

I had to see Jackie Robinson, the man who was going to somehow wreck everything. So the next day, another kid and I started walking to the ballpark early.

We always walked to save the streetcar fare. It was five or six miles, but I felt about baseball the way Abe Lincoln felt about education.

Usually, we could get there just at noon, find a seat in the grandstand, and watch some batting practice. But not that Sunday, May 18, 1947.

By noon, Wrigley Field was almost filled. The crowd outside spilled off the sidewalk and into the streets. Scalpers were asking top dollar for box seats and getting it.

I had never seen anything like it. Not just the size, although it was a new record, more than 47,000. But this was twenty-five years ago, and in 1947 few blacks were seen in the Loop, much less up on the white North Side at a Cub game.

That day, they came by the thousands, pouring off the northbound Ls and out of their cars.

They didn’t wear baseball-game clothes. They had on church clothes and funeral clothes·suits, white shirts, ties, gleaming shoes, and straw hats. I’ve never seen so many straw hats.

As big as it was, the crowd was orderly. Almost unnaturally so. People didn’t jostle each other.

The whites tried to look as if nothing unusual was happening, while the blacks tried to look casual and dignified. So everybody looked slightly ill at ease.

For most, it was probably the first time they had been that close to each other in such great numbers.

We managed to get in, scramble up a ramp, and find a place to stand behind the last row of grandstand seats. Then they shut the gates. No place remained to stand.

Robinson came up in the first inning. I remember the sound. It wasn’t the shrill, teenage cry you now hear, or an excited gut roar.

They applauded, long, rolling applause. A tall, middle-aged black man stood next to me, a smile of almost painful joy on his face, beating his palms together so hard they must have hurt.

When Robinson stepped into the batter’s box, it was as if someone had flicked a switch. The place went silent.

He swung at the first pitch and they erupted as if he had knocked it over the wall. But it was only a high foul that dropped into the box seats. I remember thinking it was strange that a foul could make that many people happy. When he struck out, the low moan was genuine.

I’ve forgotten most of the details of the game, other than that the Dodgers won and Robinson didn’t get a hit or do anything special, although he was cheered on every swing and every routine play.

But two things happened I’ll never forget. Robinson played first, and early in the game a Cub star hit a grounder and it was a close play.

Just before the Cub reached first, he swerved to his left. And as he got to the bag, he seemed to slam his foot down hard at Robinson’s foot.

It was obvious to everyone that he was trying to run into him or spike him. Robinson took the throw and got clear at the last instant.

I was shocked. That Cub, a hometown boy, was my biggest hero. It was not only an unheroic stunt, but it seemed a rude thing to do in front of people who would cheer for a foul ball. I didn’t understand why he had done it. It wasn’t at all big league.

I didn’t know that while the white fans were relatively polite, the Cubs and most other teams kept up a steady stream of racial abuse from the dugout. I thought that all they did down there was talk about how good Wheaties are.

Late in the game, Robinson was up again, and he hit another foul ball. This time it came into the stands low and fast, in our direction. Somebody in the seats grabbed for it, but it caromed off his hand and kept coming. There was a flurry of arms as the ball kept bouncing, and suddenly it was between me and my pal. We both grabbed. I had a baseball.

The two of us stood there examining it and chortling. A genuine major-league baseball that had actually been gripped and thrown by a Cub pitcher, hit by a Dodger batter. What a possession.

Then I heard the voice say: “Would you consider selling that?”

It was the black man who had applauded so fiercely.

I mumbled something. I didn’t want to sell it.

“I’ll give you ten dollars for it,” he said.

Ten dollars. I couldn’t believe it. I didn’t know what ten dollars could buy because I’d never had that much money. But I knew that a lot of men in the neighborhood considered sixty dollars a week to be good pay.

I handed it to him, and he paid me with ten $1 bills.

When I left the ball park, with that much money in my pocket, I was sure that Jackie Robinson wasn’t bad for the game.

Since then, I’ve regretted a few times that I didn’t keep the ball. Or that I hadn’t given it to him free. I didn’t know, then, how hard he probably had to work for that ten dollars.

But Tuesday I was glad I had sold it to him. And if that man is still around, and has that baseball, I’m sure he thinks it was worth every cent.