To celebrate Native American Heritage Month, we’ve put together a reading list highlighting books by and about Indigenous individuals and communities. With these books from

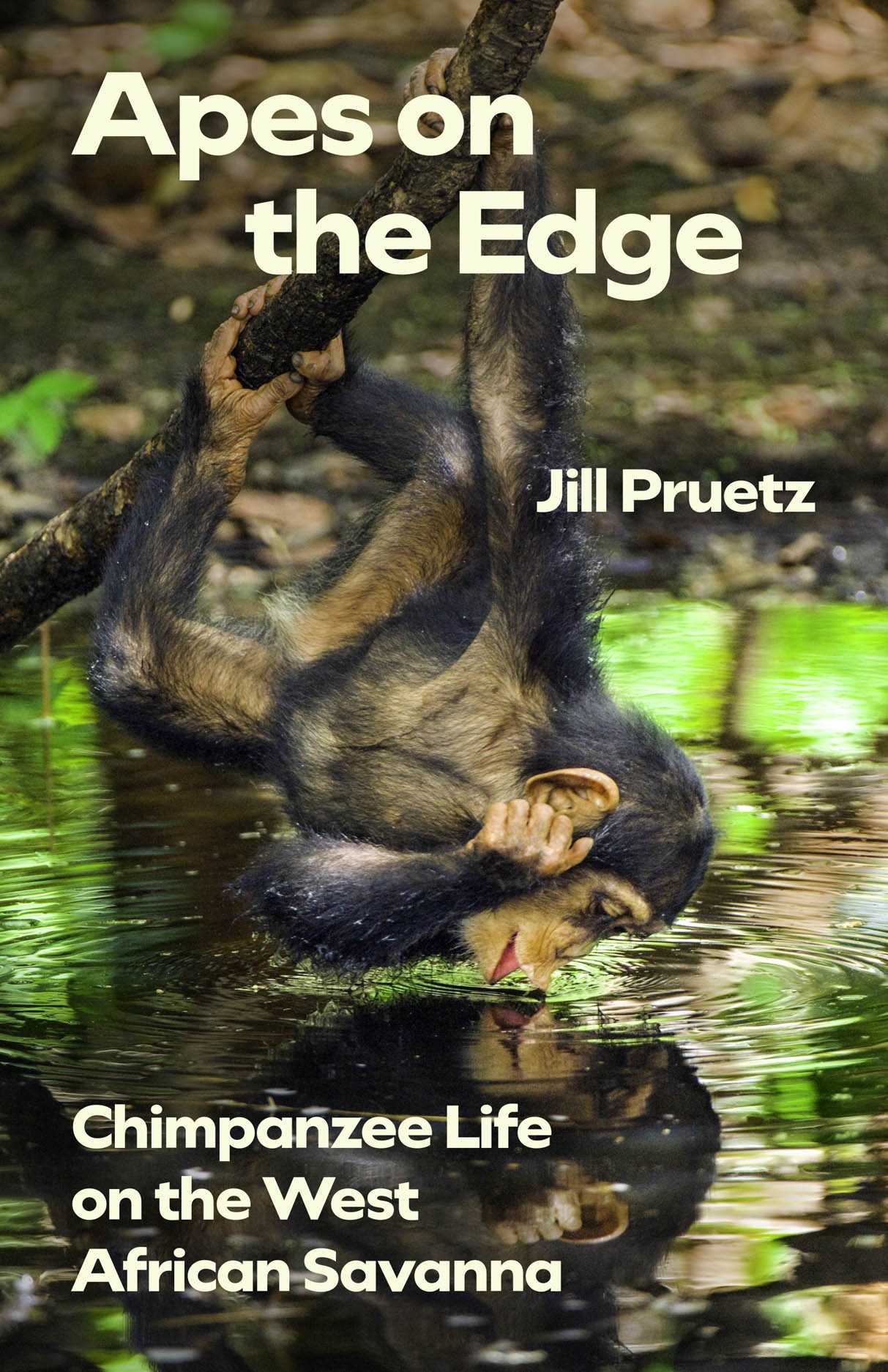

Fongoli chimpanzees are unique for many reasons. Their female hunters are the only apes that regularly hunt with tools, seeking out tiny bush babies with

In The Pandemic Workplace, anthropologist Ilana Gershon turns her attention to the US workplace and how it changed—and changed us—during the pandemic. In this excerpt, we

In the abstract, trust in both “expertise” and “the science” has been touted as panaceas to our ongoing crisis of misinformation and outright lies, but

To celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day, we’ve assembled a reading list highlighting the lives of Indigenous individuals and the history of their communities that have lived

With the current war in Sudan unleashing even more violence and suffering in the West Darfur region, it’s more important than ever to bring attention

Minoritarian Liberalism is a mesmerizing ethnography of the largest favela in Rio, where residents articulate their own politics of freedom against the backdrop of multiple

The music of the Ethiopian diaspora rings around the world, testifying to the experiences of those exiled from their homeland and serving as a keystone

Marshall Sahlins, a giant in the field of anthropology and a celebrated Press author, died earlier this week at his home in Hyde Park. Best

To celebrate the release of our exciting new translation of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s iconic work, La Pensée sauvage, we’re sharing a sneak peek at the translators’ intro.