The University of Chicago Press is celebrating Pride Month with a reading list of recent books from Chicago and our client publishers that help illuminate

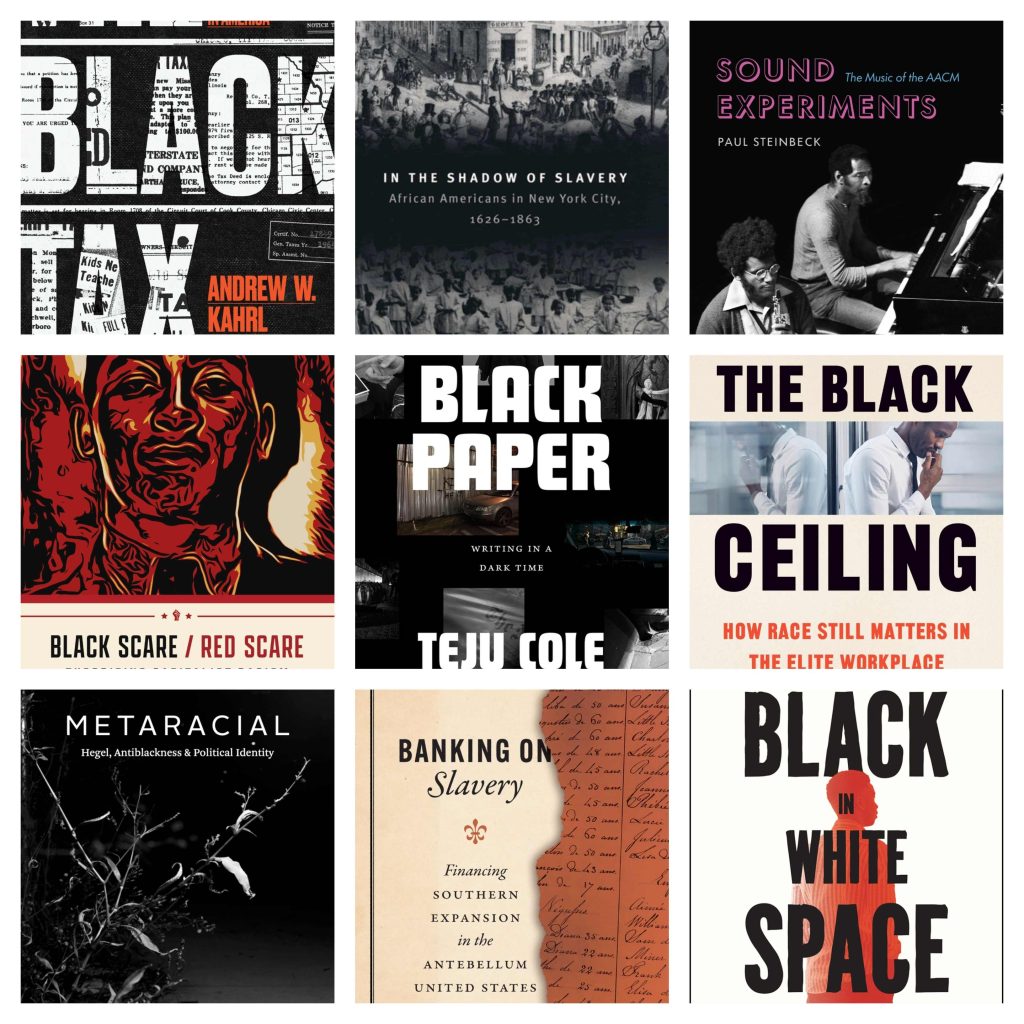

As we take time to celebrate Juneteenth, we have assembled a collection of works highlighting the lives of Black individuals and the history of African

The Journal of African American History is seeking submissions for a 2027 special issue titled “Black Women’s History in the Twenty-First Century: Engaging the Future.”

In recognition of Black History Month, we’ve curated a reading list spotlighting the rich voices of Black poets and literary authors. These works delve into

To honor Black History Month, we have assembled a collection of works highlighting the lives of Black individuals and the history of African American communities

Founded on Chicago’s South Side in 1965 and still thriving today, the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) is the most influential collective

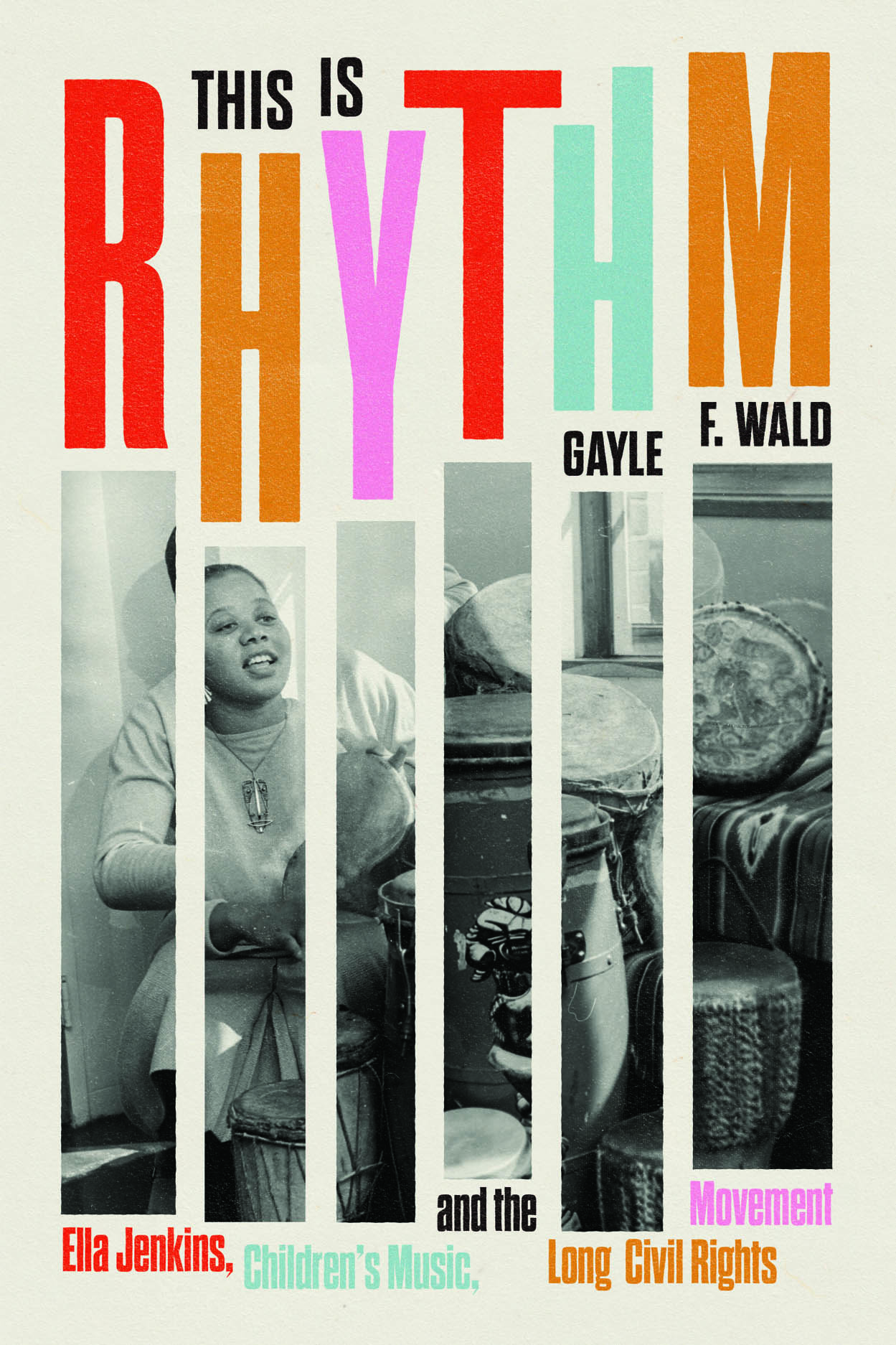

This June, we invite you to pick up a book that celebrates African American creativity, culture, and history. We’ve selected a new study that highlights

In Street Scriptures: Between God and Hip-Hop Alejandro Nava explores an important aspect of hip-hop that is rarely considered: its deep entanglement with spiritual life.

The late Chicagoan George Nesbitt could perhaps best be described as an ordinary man with an extraordinary gift for storytelling. In his newly uncovered memoir—written

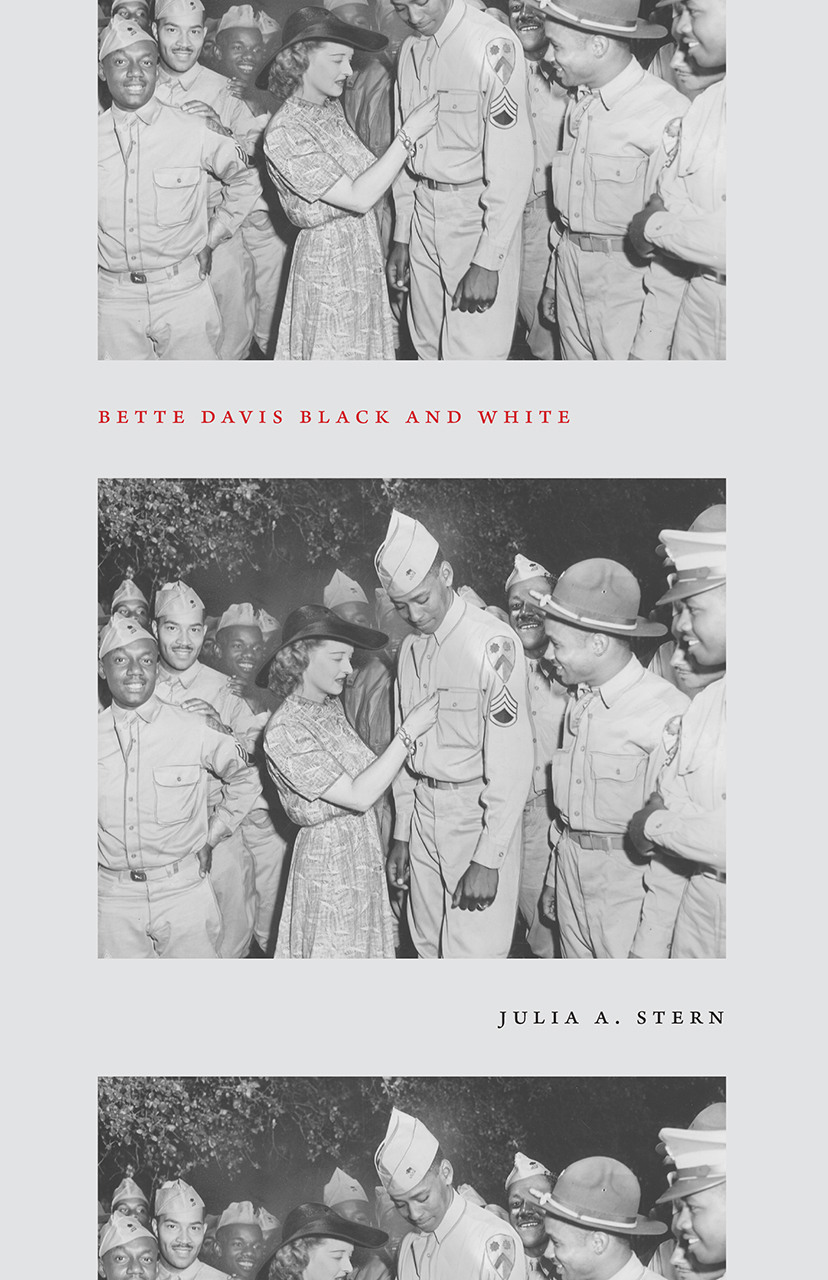

Bette Davis was not only one of Hollywood’s brightest stars, but also one of its most outspoken advocates on matters of race. In Bette Davis Black