On November 4th, residents of New York City will be casting their votes for mayor. It is an election that many in the United States

Does today’s political moment have you asking “How did we get here?” If so, we have a reading list that includes histories of American commerce

In today’s never-ending news cycle, it can be hard to stay grounded and make sense of the flood of information. So, we offer here a

Ahead of the 2024 Presidential Election, today’s politics reflect one of the most polarized ideological landscapes in US history and, as a result, America’s democratic

As Americans digest the first—and possibly last—Presidential Debate, many questions now loom even larger than before concerning the future of American democracy. Today’s politics reflect

In The Lost Promise: American Universities in the 1960s, Ellen Schrecker illuminates how American universities’ explosive growth intersected with the turmoil of the 1960s, fomenting

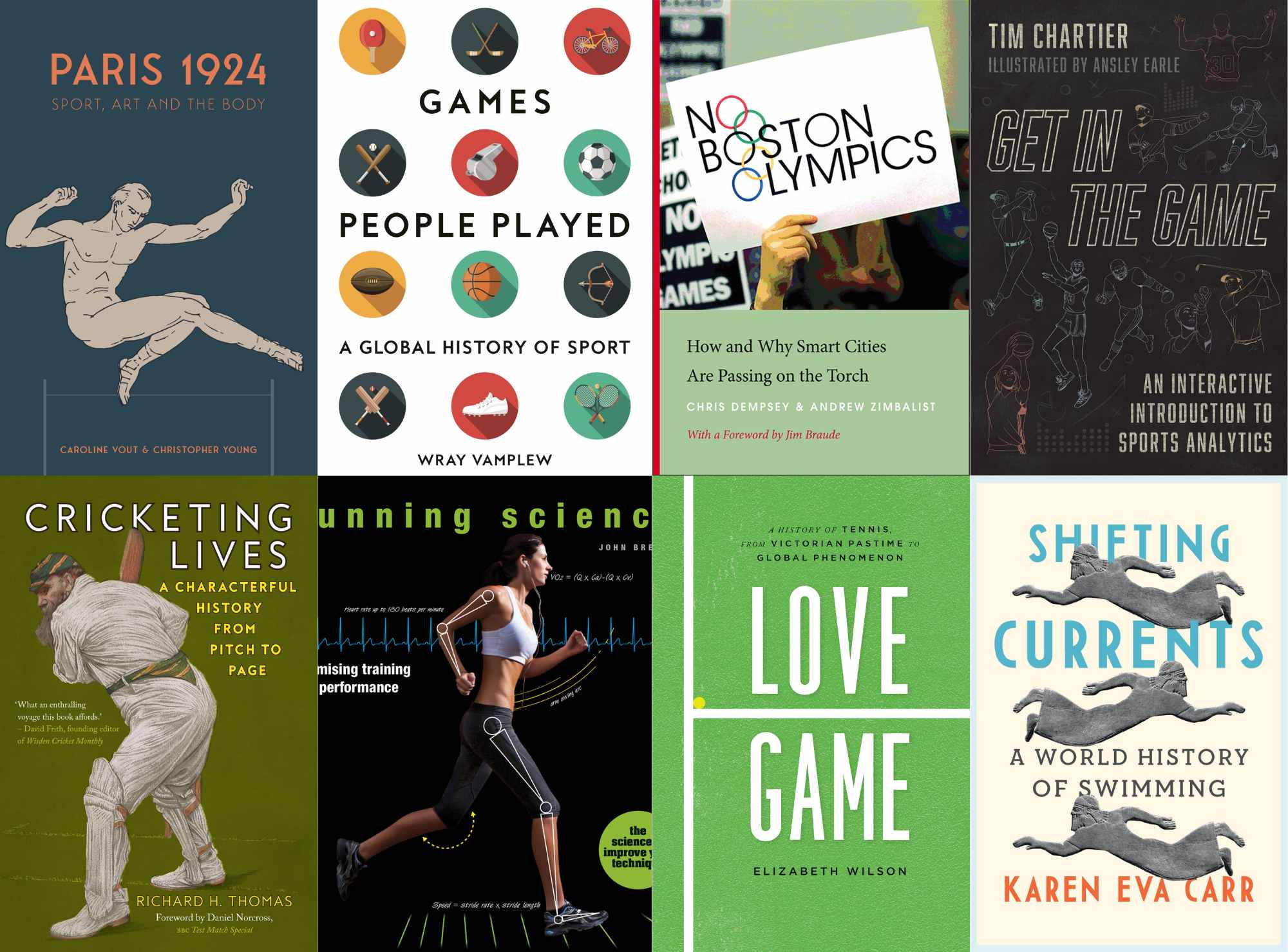

In honor of the 2024 Olympic Games, kicking off tomorrow in Paris, we’ve put together a list of our favorite books on sports history and

In honor of Women’s History Month, we’re sharing a collection of books that have a special focus on the issues and history surrounding women’s health.

When Kansas City and San Francisco take the field for Super Bowl LVIII, they will play in a competition that has been revolutionized by data

To honor Black History Month, we have assembled a collection of works highlighting the lives of Black individuals and the history of African American communities