Scott Esposito on Wayne Booth

Why do university presses matter? That’s what’s at stake for AAUP’s University Press Week, a celebration of the Association of American University Presses’ 75 years of commitment to promoting the work and interests of nonprofit scholarly publishers. At some point, the answer to that question was more or less obvious; in 1937, when the AAUP was founded, it’s mission was inferred from a decade’s worth of cooperative activities—a joint catalog, shared direct mailing lists, cooperative ads, and an educational directory. Since then, scholarly publishing has become tantamount to the production of knowledge it chooses to disseminate—it’s diverse in its platforms; complex in its shepherding and inclusion of disciplines; rich in its roster of scholars, critics, editors, and translators; and acute in its responses to the shifting parameters of technology, the auspices of funding, and the risk of institutionalization. No static thing, this.

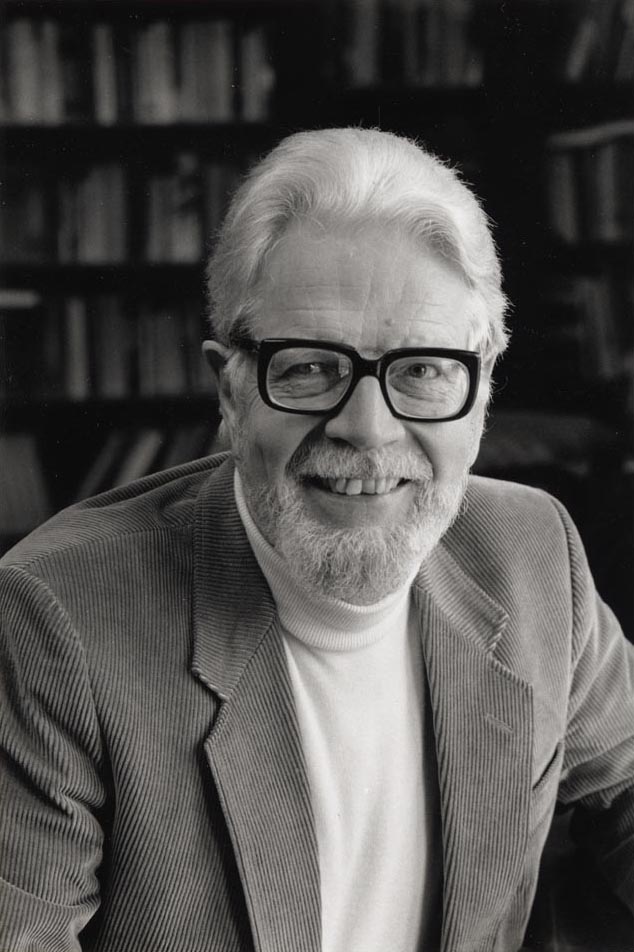

We asked editor, writer, and literary critic Scott Esposito, whose online journal the Quarterly Conversation bears significant responsibility for the discovery of Sergio De La Pava’s self-published debut novel A Naked Singularity (republished by the University of Chicago Press in 2012), to help us fly our flag. Over conversation at a dim, happy-hour bar in San Francisco’s financial district, we asked Esposito: if given the choice, is there a particular work we’ve published that you feel has contributed to your own engagement with criticism? Esposito’s answer was swift and definitive. When you read his riff on Wayne C. Booth’s Modernist Dogma and the Rhetoric of Assent below, you’ll be illuminated as to how this “philosophy of good reasons,” first published in October 1974, continues to assert the formidable and irreplaceably eloquent role Booth held as both a literary critic and scholar of rhetoric in the twentieth century. It suffices to say that he wrote some of the most influential criticism of our times, and we couldn’t think of a better reason for why university presses matter than their continued commitment to foster thinkers like Booth and to take pride in watching their ideas blossom for another generation.

***

I find it impossible to read Wayne C. Booth and not come away illuminated. Though he’s generally classified as a literary critic, Booth was really much more than that. He was an amazingly well-read, dedicated thinker who showed how questions about literature were really questions about human perception and the philosophies with which we approach life.

As a writer, Booth was never showy, and his style is anything but ostentatious. One imagines that, instead of trying to produce catchy one-liners, he strove most of all for clarity in his writing, trusting in the depth of his thoughts and originality of his arguments to provide that added zing that so many lesser thinkers attempt to contrive through cloying prose and overzealous forms. Reading Booth, one feels in the presence of a mind whose remarkable honesty and humility is rewarded with great rigor—just try and read him and not feel that your own reading has been dwarfed by his. (As an added treat, many of Booth’s footnotes feel more like miniature essays than extended parentheticals. They are paragons of the form.)

Booth turned his mind to some of the biggest questions in literature—how it works, whether or not it is moral, why irony had gained such ascendance over it by the middle of the twentieth century—and I feel that he made lasting contributions. Reading his books as much as fifty years later, they still feel relevant, their thought capable of shaking you out of complacency. Though it is not uncommon to find critics who can give erudite, nuanced readings of texts, it is almost impossible to find critics who can credibly do what Booth did, again and again: take literature and make it feel essential to life’s big questions.

For a while now, I have felt that Booth’s Modernist Dogma and the Rhetoric of Assent (one thing Booth lacked was a gift for titles) was extraordinarily ahead of its time. Booth published it in 1974, just as it seemed US politics and society were reaching a nadir of cynicism and irony, and the book is an all-out assault on the doctrine of doubt, which he associated with the teachings of modernism that he argued were predominant in Western society. In the book Booth himself admits to having once been in thrall to doubt (his conversion toward, and then away from, Bertrand Russell is documented here), and his explanation of why he changed his mind forms the cornerstone of an edifice of belief. Though history proved that Western culture could fall to far greater depths of cynicism and irony than was possible even in 1974, I would argue that the turn toward belief that Booth hoped for in this book is now underway. His reasons for believing, as well as his advocacy of the American pragmatist philosophers’ thoughts on those matters, are now hugely relevant.

Of course, as a student of Kafka, Beckett, Mann, Bernhard, and so many others, I understand the allure of doubt and, indeed, its relevance to a world still very much built on individualism, spiritual uncertainty, and political misdirection. Yet Booth’s book is one of a few key reads that have oriented my mind toward belief and, I think, shown me ways to take the next step beyond what Booth called the “modernist dogmas.”

Wayne Booth should most definitely continue to be read. To be blunt, his thoughts are simply indispensable to any serious student of literature. And anyone who is curious about the world and seeks to live an examined life will find his thoughts almost equally necessary.

Scott Esposito is the editor of the Quarterly Conversation, a web journal of literary reviews and essays, and the coauthor (with Lauren Elkin) of The End of Oulipo?, available from Zero Books in January 2013.

***

Up next? Jason Weidemann, senior acquisitions editor in sociology and media studies at the University of Minnesota Press, on a recent trip to Cape Town—and the implications for scholarly publishing. For additional information about #UPWeek and to see the full schedule for its associated blog tour, click here.