“The name of the game is gamesmanship”: An excerpt from Veeck—As in Wreck

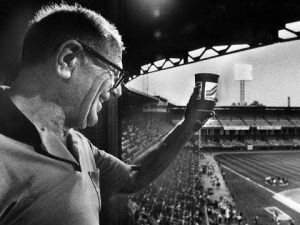

Any time you go to a baseball game today, you’re experiencing the legacy of Bill Veeck (1914–1986). Fireworks shooting from the scoreboard? Veeck. Concession stands all over the park? Veeck. T-shirt cannons and bands and on-field antics? Well, he didn’t have the tech to do that first one, but it’s definitely in a family with the latter two, and those were Veeck to a T. Oh, and when he was just a young man, working for his father, owner of the Chicago Cubs, he sold the team on growing the ivy.

In a long career as a frequently cash-strapped owner of some, well, pretty bad teams, Veeck pursued innovation like few other figures in all of baseball history. Though he’s now best known for a stunt in 1951 in which he sent a 3-foot, 7-inch man named Eddie Gaedel to the plate in a White Sox game, wearing the uniform number 7/8, Veeck’s most lasting contribution to the game was to remind everyone—but particularly owners—that it was being put on for the fans, and that meant it should always be entertaining. As Ed linn, who teamed up with Veeck in 1962 to write his classic memoir of his time in the game, “Veeck—As in Wreck”, “What Bill Veeck did, he wasn’t only the first, and he wasn’t only the best. He was the only.”

The University of Chicago Press proudly returned “Veeck—As in Wreck” to print in 2001. In the excerpt below, Veeck tells the story of one of his most risky bits of gamesmanship.

There was one final bit of gamesmanship I came very close to using, something that would have brought about rioting in Boston, a beating of editorial breasts throughout the nation and a change in the rules, all within 24 hours.

Our magnificently written rules read that “the manager of the home team shall be the sole judge as to whether a game shall not be started because of unsuitable weather conditions or the unfit conditions of the playing field.”

The manager, in this instance, means the front office.

Clubs through history have called off relatively meaningless games because of bad weather even though to the eyes of the casual observer the sun seemed to be shining brightly. Out of a decent respect for the opinion of mankind, it is customary to give such excuses as “threatening weather” or “wet field.” There is nothing in the world, though, to prevent me from saying the field is unfit because I had a nosebleed behind first base.

I had always dreamed of the day when a pennant race would come down to the last day and I would be faced with a situation where it was to my benefit not to play that final game. In 1948, that was exactly the situation confronting me.

We were one game ahead of the Red Sox and scheduled to end the season against the Detroit Tigers. The Tigers had their best pitcher, Hal Newhouser, ready to go against us. The Red Sox were playing the Yankees. If the Red Sox won and we lost, there would be a tie for first place, which would necessitate a playoff game. If we did not play, we would win the championship no matter what the Red Sox did. It had already been determined, in a special drawing, that if a playoff game became necessary it would be played at Fenway Park where the Red Sox were practically unbeatable.

In short, we had nothing to gain by playing the game and the world and all to lose. I called the weather bureau, and the forecast was “possible showers.”

I looked this situation squarely in the eye—and I quavered. A voice within me–Iet us call it, for lack of a better word, conscience—said, “You can’t do it. It isn’t fair to the players to brand them forever as the team that won the pennant by ducking out on the final game.” A contending voice within me—let us call it, for lack of a better name, Bill Veeck—answered, “Come on, you jerk, this is what you’ve been waiting for.”

I didn’t trust myself. I hastily put in a call to the league president–let us call him, for the sake of accuracy, Will Harridge—and I told him, “Under the rules, I can determine what the weather is and how the field looks. I can call off the game without giving any reason.”

“You wouldn’t do that,” Will said. Will spent the best years of his life telling me I wouldn’t do things I went right out and did.

“Will,” I said, “I have a strange feeling that if a cloud crosses the sun tomorrow morning, I am going to call off the game. I am willing to surrender my prerogative to your office. You’d better come down here or send a representative from your office.”

There was a long pause. Will was trying to figure out what my angle was. You send out a cry for help along the leased wires of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company and they sit there and wonder what your angle is.

“Come on, Bill,” he said. “You’re going to have a full house. You wouldn’t throw 80,000 people away.”

“We’ve already drawn all the people anybody could want,” I told him. “What’s another 80,000? Especially when I’m sure of at least two World Series games if I don’t play.”

Harridge sent down Tommy Connolly and Cal Hubbard to rule on the weather. It was a beautiful day and we lost the game. “You see, Veeck,” I kept muttering, “that’s what you get for being honorable.”

_______

In all my years in baseball, there has been only one game I have been sure–absolutely sure–of winning. That was the playoff game in Boston. All through the year, Lou Boudreau had given us the play we needed to stay alive or the hit we needed to win. I knew absolutely that, whatever had to be done to win this one, Lou would do it. Before the game, crossing from the third-base dugout to our first-base box, I asked Larry Atkins to make arrangements for a victory party at the Kenmore.

Lou had called Hank Greenberg and me down to the dugout before the game to ask our advice on his lineup, something he had never done before. He wanted to know if it was all right with us if he played Allie Clark, a utility outfielder, at first base. I said, “Louie, you’ve managed the ball club without aid all year. I’m certainly not going to be looking over your shoulder in the most important game of all.”

It was a daring move. With the Red Sox starting Denny Galehouse, an old-timer who had control but no particular speed or breaking stuff, Lou had decided to forego the lefty-righty percentage. Instead, he was playing the other percentage, Fenway Park’s looming left-field wall, by packing his lineup with right-handers from top to bottom. Including Clark. The only thing about it was that Clark had never played an inning of first base in the major leagues.

First base is not the most difficult position in the world. But if Clark made an error which cost us the game and the pennant, Lou would be attacked from coast to coast for taking that kind of a chance in such a climactic game. If, on the other hand, Allie won the game for us with a dramatic home run, Lou would be hailed nationally for his courage, his imagination and his intellectual honesty.

As it was, Allie Clark was the most inconspicuous player on the field. He was the only man in our lineup who failed to get a base hit. Not a ball was hit anywhere near him all day. Boudreau’s great gamble went unmarked and unremarked upon. It was as if the South had fired on Fort Sumter and missed.

The victory party was an action party aimed, among other things, at releasing the tension that had been building up through the season. There was another reason. I like parties. This one was restricted to our players and our writers. The only outsider was a little fellow who had come down from Cleveland for the game and had been invited, on the spur of the moment, by Keltner and Tipton. As the evening wore on and tempers began to flow . . . I mean flare, either Tipton or Keltner–things were getting a bit kaleidoscopic at that point–decided their guest was really an intruder so he picked up the little guy and threw him out. The other, feeling his duties as a host more keenly, ran out to the hall, picked him up and threw him back in. Joe Gordon, finding the situation of interest, was willing to lend them both a hand. It was almost like calisthenics with the poor guy being heaved in and out by the numbers. One thing led to another-with Gordon perhaps doing the leading-until Tipton and Keltner pulled off their jackets to have at each other. Over to break it up ran Hank Greenberg and myself. Hank, showing the quick reactions that were to gain him election into the Hall of Fame, arrived in time to almost get belted in the nose with the only punch thrown. Kenny and Joe, apparently feeling that their point had been made, put their jackets back on and became buddies again.

The party ended, for me, wandering around Boston with Joe Gordon until about seven in the morning. At noon, I was awakened by the sound of somebody beating upon either my head or the door. It was a fellow from Sport Magazine, and he seemed to be in some trouble. What had happened was that Sport was holding a luncheon downstairs to announce the launching of its first issue, and Ted Williams, booked as the principal speaker, had failed to show up. Good Ole Will, as everybody knows, is always available.

“I’ll stand under the shower for a couple of hours,” I told him, “and be down.”

“You can’t,” he said. “You’ve got to come down in the next fifteen or twenty minutes.”

“I’ll stand under a cold shower for fifteen or twenty minutes,” I said, “and be down.”

So I stood under a cold shower and went down and delivered one of my brilliant addresses. It couldn’t have been too bad. The next year, at Sport‘s first annual banquet, I was invited to be the featured speaker.

After the luncheon was over, I was informed that one of our troop was still missing. Gene Bearden, who had pitched the playoff victory, was apparently still celebrating somewhere in Boston, in midaftemoon. We organized a search party and finally found him. Three days later, he shut out the Braves in the third game of the World Series.

In Cleveland–and again in Chicago–I can say, without fear of contradiction by my worst enemy, I did my darnedest to get the World Series tickets to the fans who had supported us through the year.

As soon as we got the go-ahead to accept World Series orders, which was before we had the pennant clinched, I told Larry Atkins to take care of any of “our” people who wanted tickets: busboys, bartenders, men’s-room attendants, cabdrivers, waitresses, shoeshine boys and the telephone operators at the hotel and at the hospital.

“Anybody?” he said. “You’re crazy. It will be everybody!”

Anybody or everybody, I told him. These were the people who had supported us from the beginning and had helped us from day to day and they deserved to be in on the victory. I gave away 250 sets of tickets to that strata of Cleveland society and I paid for them all myself.