Five Questions with Sam Stephenson and Alan Thomas about the Work of W. Eugene Smith

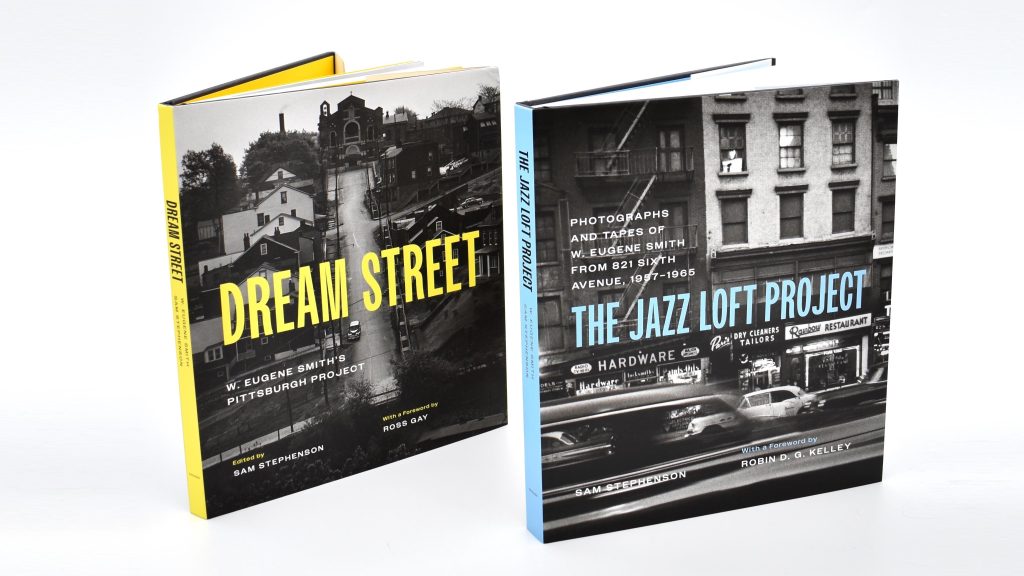

This year, the University of Chicago Press is publishing new editions of two stunning photography collections by famed American photographer W. Eugene Smith. We sat down with the author and editor of the books, Sam Stephenson, along with the Press’s editorial director, Alan Thomas, who brought these two books to the Press. Sam and Alan discuss how these projects formed and why the work of Gene Smith is still important to photography today. Alongside insights from Sam and Alan, we’re highlighting a selection of just a few of the gorgeous photographs included in the books.

How did this project come to Chicago—when did this relationship form?

Sam Stephenson: The University of Chicago Press is a natural home for these two books, because my research on these two books was supported by Chicago’s Reva and David Logan Foundation since 1999. The Foundation’s offspring foundations, the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation and the Revada Foundation, supported these new editions, as well. Plus, Chicago is widely considered to be one of the best and smartest publishers in the business.

Alan Thomas: There were also compelling editorial reasons for us to pursue these books. In addition to the Press’s interest in the history of photography, we have a tradition of publishing books about jazz and about urban life. The Jazz Loft Project resonates, for example, with Benjamin Cawthra’s excellent Blue Notes in Black and White: Photography and Jazz, which we published in 2011, and Dream Street with our many books on the transformation of American cities. I should mention that Sam and I were first put in touch by Jeff Posternak of the Wylie Agency, who shares our passion for photography.

Jazz Loft images: © 1957–1965, 2023 by the Heirs of W. Eugene Smith

Why bring these books back into print now?

SS: It’s the right time. Dream Street was originally published by Norton in 2001 and the Jazz Loft Project by Knopf in 2009. Both publishers let those books go out of print over time. These new editions really sparkle, benefitting from the press’s ace design staff and also new technology. It is the right time to freshen up these books.

AT: In the photography world more generally, there is a surge of interest in the history of photography books, with publishers reissuing classic works for which there is a new demand. Often these new editions are augmented in one way or another. In this case, we’re thrilled to have new forewords to the books, from Robin D. G. Kelley and Ross Gay.

What’s the importance of W. Eugene Smith and his legacy today?

SS: Smith had a feverish style of old-fashioned darkroom printing. In the age of digital photography, in which every person has a very good camera in their pocket at all times, his very slow methods are an important legacy. There is evidence that darkroom printing is returning, in the same way that vinyl records are returning. The reproductions in these two books were made almost entirely from his original prints, not from his negatives, so his printing legacy is extended. Beyond his technique, his legacy concerns showing the world something they wouldn’t have seen if he hadn’t captured it.

AT: Smith also lived a high-risk creative life that holds intrinsic fascination today, and the open-ended, incomplete nature of these two projects is a testimony to that. I recommend Sam’s earlier book, Gene Smith’s Sink, as a compelling inquiry into Smith’s life.

Dream Street images: © 1955–1957, 2023 by the Heirs of W. Eugene Smith

What, for you, are some of the most exciting aspects of these two photography collections?

SS: In these two bodies of work, Smith’s audacity is profound. He went to Pittsburgh for a two-week assignment to produce one hundred photographs and he spent four years on the project, won two successive Guggenheim awards, and amassed tens of thousands of photographs. Then, in the throes of trying to finish that project he moved into a dilapidated loft in Manhattan and proceeded to wire the building and make thousands of photographs and thousands of hours of surreptitious tape recordings. What were his goals? I’m still not sure. There was no reasonable way to finish either project. They were unfinishable. I find that exciting. We’re lucky today that he did it. What he achieved in both projects is like urban fieldwork of mid-century America, two very different ways of doing it. My job as a writer and editor was to provide context and scaffolding for Smith’s materials to come alive.

AT: I will add only that Sam’s work in transforming these unfinished projects into book form is one of the great editorial feats in the history of photography.

Sam, let us give you the last word. Anything else you’d like to share about this project?

I’d just like to stress my gratitude to the Logan family for their support over all these years. Jon Logan in particular was instrumental in supporting these two new editions. And I’d like to thank the press for their tremendous care and craft in putting the books together so beautifully.

Sam Stephenson is the author of a biography of W. Eugene Smith, Gene Smith’s Sink, as well as Dream Street: W. Eugene Smith’s Pittsburgh Project and The Jazz Loft Project: The Photographs and Tapes of W. Eugene Smith from 821 Sixth Avenue. He is also the ghost writer of Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You, a memoir by Lucinda Williams. In 2019, he won a Guggenheim Fellowship for his work in progress about the band Jane’s Addiction. He can be found on Twitter at @SamStephenson12.

Alan Thomas is the editorial director of the University of Chicago Press.

Dream Street and The Jazz Loft Project are now available from our website or your favorite bookseller.