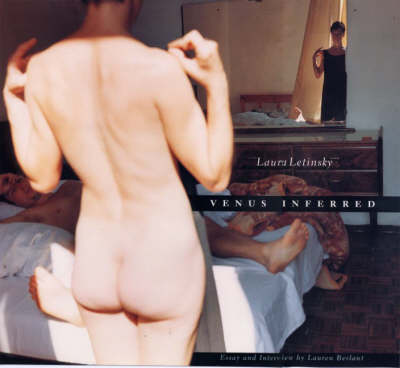

Laura Letinsky: Venus Inferred

Laura Letinsky, Untitled #54, 2002. © Laura Letinsky

“People want perfection, even if it’s a falsehood,” is the observation proffered by photographer Laura Letinsky in a recent New York Times overview of her work, establishing the stakes her images subtlely, and often intimately overturn. The article goes on to consider Letinsky’s assignments for a variety of glossy magazines—Bon Appétit, Brides, and Martha Stewart Living, among them—that would seemingly eschew her favored aesthetic: the banal objects of our everyday (foods, bodies) in states of disarray, consuming and consumptive, half-eaten, leg-locked, caught mid-meal or in flagrante delicto.

But instead of rejecting Letinsky’s painstakingly detailed dis-compositions, these otherwise static, commodity-infused, well-coiffed periodicals have embraced the “tiny details” of her “chaos.” If there is room in late-capitalist culture for a movement like slow food, with its preservation of traditional cuisines and pursuit of sustainability, it might be worth asking if Letinsky’s work responds to a virtual slow cultural hegemony—here the dominant worldview, with its norms that sustain our existence (how we view the rules of eating, sleeping, sexing) still impinges its implications upon us, but our resistance is to strip them bare and backward. Letinsky’s photographs show the world as it is—contextualization isn’t lost, but for a moment it seems profoundly deferred by the immediacy of legs intertwined or a cantaloupe slowly (though not yet visibly) rotting, once glasses have clinked, and bodies have left the table.

In 2000, we published Letinsky’s Venus Inferred, a selection of 46 photographs of lovers in their inhabited domestic spaces, a realm some theorists call “the intimate public sphere.” The images are instantly recognizable as “ordinary,” in that what they portray is the version of these lovers as seen by themselves, were the camera substituted with a mirror: private/public, slightly undone, discomfited in their creature comforts, imperfectly absorbed by their human skin, parts, bodies. Like Letinsky’s food series, they might jolt us with a particular kind of vulnerability, as the most animate kind of still life.

In her essay accompanying the images “The Sublime and the Pretty,” scholar Lauren Berlant writes:

“What ensues is a kind of fetishism. The body, the scene of the a desire to cultivate civic personhood, nonetheless overwhelms the principles of education that become associated with it. This links the crisis of politico-aesthetic form to the ontology of the photograph. Walter Benjamin suggests that photography always enacts violence on its object, but not only because it rips objects from their original reality. His bigger concern is in the way that the object’s meaning then leans heavily on the caption and the captioner. Likewise it could be said that the body at the center of the aesthetic training in subjectivity becomes socially intelligible by being trained to photograph itself, to zone itself like, again, the couples who pose themselves to be witnessed by Letinsky’s work. Their bodies become meaningful insofar as they get captioned, clothed, or contextualized within the syntax of propriety. The hierarchies of value that caption in order to normalize sensual self-understanding become then, one way or another, names for what the human expresses in his encounters with beautiful and painful or sublime processes or experiences. At this juncture any debate that opposes cultural and materialism politics seems to miss the point—that they collaborate, even when in apparent antinomy.”

Laura Letinsky, Untitled (Adrienne and Stephan), 1992. © Laura Letinsky

Later, in the interview between Berlant and Letinsky that closes the collection, Letinsky’s attention to our ability to supersede the norms of our human experiences gets drawn out:

LB: So on the one hand, you’re like some ethnographer of the normal, and on the other hand, you feel like you’re encountering and picturing the enchantment of love that lifts the normal from itself, to what feels like a unique space?

LL: Right, it’s about the relationship between privacy and particularity. At first I had a sense of being a scientist or an explorer going into people’s private space. Then I wondered whether it was a private space, since its conventionality works against that. Not only in love’s promise, but in the singularity of the spaces, the sheets, the pajamas, the coffee cups. These details evaded the generic and particularized the couples. I became interested in the desire to be normal, and how people tried to live that dream out. And I saw how people could never quite do this, and yet still tried.

Sex is normal as shit; sex is un-normal as shit. Sex is the hounds of hell, and intimacy—those feelings cauterized around bodies enmeshed and ideas enabled—is a never ceasing bark, yipping, chasing, trying.