John Heartfield: Agitated Images

John Heartfield (born Helmut Herzfeld, 1891–1968)—montagist, rotugravurer, shock animator, and inspiration for the song “Mittageisen” by Siouxsie and the Banshees—literally changed the face of political art in the twentieth century. For Heartfield, the montage form he famously adapted not only allowed him to maintain control of legibility—by jarring expectations of genre and content in order to solicit the gaze—but to expose fascism by harnessing images as weapons capable of disseminating information in discursive ways, on as broad a scale as possible.

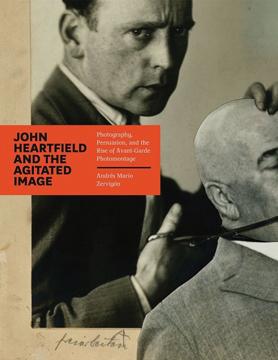

In John Heartfield and the Agitated Image: Photography, Persuasion, and the Rise of Avant-Garde Photomontage, Andrés Mario Zervigón charts the evolution of Heartfield’s photomontage from an act of antiwar resistance into one of the most important combinations of avant-garde art and politics in the twentieth century. What follows below is a short excerpt from the book, which traces then-Herzfeld’s opposition to the war to new acts of performative resistance, found in both new forms and new stakes w/r/t personal identity.

***

John Heartfield, The Performance

Perhaps not coincidentally, near this moment in June 1917, Helmut Herzfeld informally Anglicized his name as a brazen protest against the war. The first extant mention of this new moniker is in a letter from Else Lasker-Schüler to Franz Jung dated “middle of August 1917.” there she refers to her young artist friend as “J. H.” Seemingly inspired by Jung’s aggressiveness and following on the model established by Herzfelde and George Grosz, Heartfield now began the mature phase of his lifelong performance.

Heartfield’s name change constituted an act of resistance against the waves of nationalist jingoism that had washed over his countrymen since the declaration of war in August 1914. For example, Ernst Lissauer, one of the poets who had collaborated with the “hurrah patriotism” that Lasker-Schüler’s circle so earnestly despised, penned an anti-British song with the catchy refrain “We love in unity, we hate in unity, we all have but one enemy: England!” The sentiment took hold of the popular imagination and even led to a transformation of public salutation. Whereas before the war, people in Germany generally greeted each other with the familiar “guten Tag,” now they often bellowed, “God punish England!” The expected response was “He’ll do so.” This everyday exchange saw Lissauer’s lyric “we hate in unity” realized in the country’s streets, stores, and parks. In expecting or even demanding a suitable response to this aggressive greeting, the average patriot could coerce those he greeted to participate in the general discourse of martial unity.

With the last issue of Die neue Jugend and Heartfield’s dramatic—but still informal—name change, we can see that the most accurate reflection of the moment came in the compositional-cum-performative force that we today recognize in the broadest sense as montage, a process of appropriation, juxtaposition, and transformation normally made at the level of spectacle. Exactly which medium was subjected to this assault seemed unimportant. Language, the written word, visual art, and photography had all failed to convey the moment’s harsh reality and instead had been used to distract Germany’s civilians with sweet and boastful visions. All of these media now demanded reinvention. The most important aspect of montage’s assault on each was the impact of the slicing itself, the snipping and jumbling that conveyed what the moment’s retrieved and transformed detritus obscured.

In this regard, Heartfield and Grosz’s postcards seem to have showcased photography’s failure, demonstrating that the medium could approximate reality only if torn from its initial context and subjected to the brutal physical conditions of the moment. The postcards had thus marked the advent of montage as a formal strategy that as not yet specific to one medium. Heartfield’s typographic inventions then realized this operation as a public gesture that seemingly reflected the moment’s chaos as a harried visual and syntactical jumble.

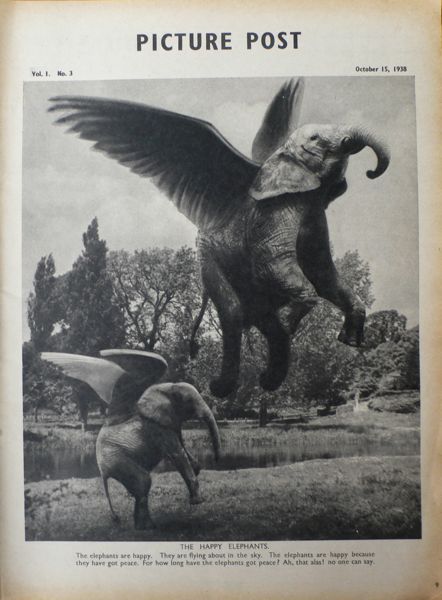

The situation would soon change, but not in a manner we might anticipate. In 1918 Heartfield decided that photography had become so complicit in ameliorative misrepresentation that even montage could no longer salvage it, at least in the context of Wilhelmine censorship. Thus, he turned to animated film, where the age’s extreme violence could finally find its most shocking realization in exploding moving images.