Microbes from Hell in Nature

From a sterling write-up of Patrick Forterre’s pursuit of the single-celled archaea, via a review of Microbes from Hell in Nature:

Forterre was fascinated by the ideas of microbiologist Carl Woese. In the 1970s, Woese realized that ‘archaebacteria’ were distinct from bacteria, for instance in the sequences of their ribosomal RNA. In 1990, Woese and his colleagues proposed to divide life into three domains: bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes. The concept has gradually been accepted, but Forterre — with microbiologists Wolfram Zillig and Otto Kandler, among others — was an early ‘believer.’

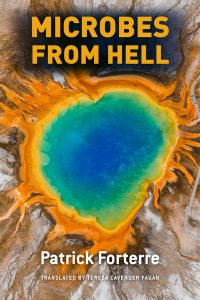

As he relates, most of the archaea that had then been isolated were extremophiles. These include hyperthermophilic microbes that thrive above 80 °C and are typically found in habitats such as deep-ocean vents. Up to the 1970s, the consensus had been that most such habitats were hostile to life, but a handful of groundbreaking microbiologists changed that. Thomas Brock, for instance, began to isolate hyperthermophilic archaea, including the genus Sulfolobus, from hot springs in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. Later, German microbiologist Karl Stetter showed that many surprising habitats, even oil fields, teemed with microbial life.

In the 1980s, Forterre began to analyse the hyperthermophilic archaea isolated by Stetter and Zillig, looking for reverse gyrase. The enzyme causes the DNA double helix to cross over on itself (supercoiling), and Forterre discovered that hyperthermophiles contain a form of it that induces positive supercoiling — adding extra twists. This enzyme, also found in hyperthermophilic bacteria, has not yet been seen in organisms growing at lower temperatures, leading to speculation that it might be one reason that hyperthermophiles can grow at such high temperatures. One theory is that the enzyme is important in sensing unpaired regions in hyperthermophile genomes, then initiating repair.

In 1999, Forterre and his technician (later wife) Évelyne Marguet joined the AMISTAD expedition of the French National Center for Scientific Research and the French Research Institute for Exploration of the Sea. Its aim was to isolate hyperthermophilic archaea from the deep eastern Pacific Ocean. Marguet gives a rousing account of her 2,600-metre dive in the submersible Nautile to gather samples from ‘smokers’. These rock chimneys form at geologically active sites on the sea floor, where superheated, metal-laden water is funnelled from vents.

Back on the ship Atalante, Marguet was enthralled to see cells growing in cultures from her samples, and isolated several Thermococcus species. She also tried to isolate the first viruses from these archaea, using methods established by Zillig. She and Forterre discovered no viruses, but they did find that Thermococcus strains produced a vast amount of membrane vesicles from cells containing plasmid DNA. Since then, large quantities of membrane vesicles have been found, particularly in ocean water, and produced by eukaryotes and bacteria. They are thought to contribute to DNA transfer between species, so they may have a role in evolution.

Ever since Forterre read Woese’s work on the identification of the archaea and its implications for the tree of life, he has wondered about a last universal common ancestor of all life. His book walks the reader through his fascinating journey to understand how life evolved. Today, Forterre believes that viruses played a vital part. Microbes from Hell, in interweaving a scientific life with the grand discovery of the archaea, is a wonderful homage to this exciting field, which continues to challenge our view of life’s origins.

To read the Nature review in full, click here.

To read more about Microbes from Hell, click here.