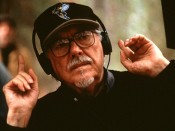

In memory of Robert Altman

Robert Altman died yesterday at the age of 81. To mark his passing and his profound influence on contemporary film, we reprint Roger Ebert’s interview of Altman as published in Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert.

Robert Altman died yesterday at the age of 81. To mark his passing and his profound influence on contemporary film, we reprint Roger Ebert’s interview of Altman as published in Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert.

Introduction

I think I’ve interviewed Robert Altman more often than anybody else in the movie business. That has something to do with his method of making a movie, which is to assemble large groups of people and set them all in motion at once. There are always visitors on the set. Altman presides as an impresario or host. He likes to introduce people. I wonder if he dislikes being alone. Kathryn, his wife of forty years, is always somewhere nearby, a coconspirator.

Once we both found ourselves at a film festival in Iowa City that was held only once. We both thought Pauline Kael was going to be there, which was why we’d agreed to come. Pauline later said she’d never been invited. Bob and I sat on a desk in a classroom and discussed the delicately moody Thieves Like Us, one of his most neglected films. Other times, I visited the sets of Health, A Wedding, and Gosford Park, and watched him rehearse the Lyric Opera adaptation of A Wedding years later.

He marched to his own drummer. After the Sundance premiere of his Gingerbread Man, he sat at a reception for a thousand people in Salt Lake City, contentedly smoking a joint. In his screening room at his original Lions Gate in Westwood, he screened rough cuts for just about anyone who wanted to come. Twice Chaz and I joined the Altmans for dinner in Chicago with mayor Richard M. and Maggie Daley; the mayor likes movies and can talk about them, and the two men had an easy rapport. Entering the restaurant on a winter night after he’d wrapped The Company, Robert swept in with him the snowy air and the aroma of marijuana. Daley looked at me and lifted an eyebrow not more than an eighth of an inch, and smiled so slyly you had to be looking for it.

Altman told me once he didn’t mind a bad review, “because without them, what does a good review mean?” He added that in my case all of my negative reviews of his work had been wrong.

CANNES, France—Yes, it was very pleasant. We sat on the stern of Robert Altman’s rented yacht in the Cannes harbor, and looked across at the city and the flags and the hills. There was a scotch and soda with lots of ice, and an efficient young man dressed all in white who came on quiet shoes to fill the glasses when it was necessary.

Altman wore a knit sport shirt with the legend of the Chicago Bears over the left pocket: a souvenir, no doubt, from his trips to Chicago to scout locations for A Wedding. He was in a benign mood, and it was a day to savor. The night before, his film 3 Women had played as an official entry in the Cannes festival, and had received a genuinely warm standing ovation, the most enthusiastic of the festival.

Because his M*A*S*H had won the Grand Prix in 1970, Altman could have shown this film out of competition. But he wasn’t having any: “If you don’t want to be in competition,” he was saying, “that means you’re either too arrogant, or too scared. So you might lose? I’ve lost before; there’s nothing wrong with losing.”

He was, as it turned out, only being halfway prophetic: three days later the jury would award the Grand Prix to an Italian film, giving 3 Women the best actress award for Shelley Duvall’s performance. But on this afternoon it was still possible to speculate about the grand prize, with the boat rocking gently and nothing on the immediate horizon except, of course, the necessity to be in Chicago in June to begin a $4 million movie with forty-eight actors, most of whom would be on the set every day for two months.

“I’d be back supervising the preparation,” Altman said, “except I’m lazy. Also, my staff knows what I want better than I do. If I’m there, they feel like they have to check with me, and that only slows them down.”

Lauren Hutton drifted down from the upper deck. She’ll play a wedding photographer making a sixteen-millimeter documentary film-within-a-film in A Wedding, and Altman’s counting on her character to help keep the other characters straight. “With forty-eight people at the wedding party, we have to be sure the audience can tell them apart. The bridesmaids will all be dressed the same, for example. So Lauren will be armed with a book of Polaroids of everybody, as a guide for herself, and we can fall back on her confusion when we think the audience might be confused.”

Fresh drinks arrived. Altman sipped his and found it good. His wife, Kathryn, returning from a tour of the yacht harbor, walked up the gangplank and said she had some calls to make. Altman sipped again.

“It’s lovely sitting on this yacht,” he said after a moment. “Beats any hotel in town.”

The boat is called Pakcha? I asked.

“Yeah,” said Altman. “Outta South Hampton. It’s been around the world twice. Got its name in one of those South Sea Islands. Pakcha is a Pacific dialect word for ‘traveling white businessman.’”

He shrugged, as if to say, how can I deny it? He sipped his drink again, and I asked if that story was really true about how he got the idea for A Wedding.

“Yeah, that’s how it came about, all right. We were shooting 3 Women out in the desert, and it was a really hot day and we were in a hotel room that was like a furnace, and I wasn’t feeling too well on account of having felt too well the night before, and this girl was down from L.A. to do some in-depth gossip and asked me what my next movie was going to be. At that moment, I didn’t even feel like doing this movie, so I told her I was gonna shoot a wedding next. A wedding? Yeah, a wedding.

“So a few moments later my production assistant comes up and she says, ‘Bob, did you hear yourself just then?’ Yeah, I say, I did. ‘That’s not a bad idea, is it?’ She says. Not a bad idea at all, I say; and that night we started on the outline.”

3 Women itself had an equally unlikely genesis, Altman recalled: “I dreamed it. I dreamed of the desert, and these three women, and I remember every once in a while I’d dream that I was waking up and sending out people to scout locations and cast the thing. And when I woke up in the morning, it was like I’d done the picture. What’s more, I liked it. So, what the hell, I decided to do it.”

The movie is about . . . well, it’s about whatever you think it’s about. Two of the women, the main characters, seem to undergo a mysterious personality transfer in the film’s center, and then they fuse with the third woman to form a new personality altogether. Some viewers have found it to be an Altman statement on women’s liberation, but he doesn’t see it that way:

“For women’s lib or against? Don’t ask me. If I sat here and said the film was about X, Y, and Z, that restricts the audience to finding the film within my boundaries. I want them to go outside to bring themselves to the film. What they find there will be at least as interesting as what I did . . .

“And I kept on discovering things in the film right up to the final edit. The film begins, for example, with Sissy Spacek wandering in out of the desert and meeting Shelley Duvall and getting the job in the rehabilitation center. And when I was looking at the end of the film during the editing process, it occurred to me that when you see that final exterior shot of the house, and the dialogue asks the Sissy Spacek character to get the sewing basket—well, she could just walk right out of the house and go to California and walk in at the beginning of the movie, and it would be perfectly circular and even make sense that way. But that’s only one way to read it.”

Altman said he’s constantly amazed by the things he reads about his films in reviews. “Sometimes,” he said, “I think the critics take their lead from the statements directors themselves make about their films. There was an astonishing review in Newsweek by Jack Kroll, for example, of Fellini’s Casanova. It made no sense at all, in terms of the film itself. But then I read something Fellini had said about the film, and I think Kroll was simply finding in the film what Fellini said he put there.

“With 3 Women, now, a lot of the reviews go on and on about the supposed Jungian implications of the relationships. If you ask me to give a child’s simplified difference between Jung and Freud, I couldn’t. It’s just a field I know nothing about. But the name of Jung turns up in the production notes that were written for the press kit, and there you are.”

The problem, he said, is that people insist on getting everything straight. On having movies make sense, and on being provided with a key for unlocking complex movies.

“It’s the weirdest thing. We’re willing to accept anything, absolutely anything, in real life. But we demand order from our fantasies. Instead of just going along with them and saying, yeah, that’s right, it’s a fantasy and it doesn’t make sense. Once you figure out a fantasy, it may be more satisfying but it’s less fun.”

For reasons having something to do with that, he said, he likes to take chances on his films: “Every film should be different, and get into a different area, and have its own look. I’d hate to start repeating myself. I have this thing I call a fear quotient. The more afraid I am, going in, the better the picture is likely to be.” A pause. “And on that basis, A Wedding is going to be my best picture yet.

“I like to allow for accidents, for happy occurrences, and mistakes. That’s why I don’t plan too carefully, and why we’re going to use two cameras and shoot 500,000 feet of film on A Wedding. Sometimes you don’t know yourself what’s going to work. I think a problem with some of the younger directors, who were all but raised on film, is that their film grammar has become too rigid. Their work is inspired more by other films than by life.

“That happened to Godard, and to Friedkin it may be happening. To Bogdanovich without any doubt. He has all these millions of dollars and all these great technicians, and he tells them what he wants and they give it to him. Problem is, maybe when he gets it, it turns out he didn’t really want it after all, but he’s stuck with it.”

Altman has rarely had budgets large enough to afford such freedom, if freedom’s the word. Although he’s had only one smash hit, M*A*S*H, he keeps working and remains prolific because his films are budgeted reasonably and brought in on time. For example, 3 Women is a challenging film that may not find enormous audiences, but at $1.6 million it will likely turn a profit.

“I made a deal with the studio,” he said, “if we go over budget, I pay the difference. If we stay under, I keep the change. On that one, we came in about $100,000 under budget, which certainly wasn’t enough to meet much of the overhead of keeping this whole organization going . . . but then of course you hope the film goes into profit.”

He always makes a film believing it will be enormously profitable, he said: “When I’m finished, I can’t see any way that millions of people won’t want to see what I’ve done. With The Long Goodbye, for example, we thought we had a monster hit on our hands. With Nashville, my second biggest grossing film, we did have a hit, but it was oversold. Paramount was so convinced they were going through the sky on that film that they spent so damned much money promoting it that they may never break even. It grossed $16 million, which was very good considering its budget, but they thought it would top $40 million, and they were wrong.”

But, of course, A Wedding will be a monster hit?

“I really hope so. If things work out the way I anticipate they will, it will certainly be my funniest film. I mean really funny. But then funny things happen every day.”

The man in white came on quiet shoes, and there was another scotch and soda where the old one had been. Altman obviously had a funny example in mind.

“I had this lady interviewer following me around,” he said. “More of that in-depth crap. She was convinced that life with Altman was a never-ending round of orgies and excess. She was even snooping around in my hotel bathroom, for Christ’s sake, and she found this jar of funny white powder in the medicine cabinet. Aha! she thinks. Cocaine! So she snorts some. Unfortunately, what she didn’t know was that I’m allergic to commercial toothpaste because the dentine in it makes me break out in a rash. So my wife mixes up baking soda and salt for me, and—poor girl.”

He lifted his glass and toasted her, and Cannes, and whatever.