The dragon still breathes fire

This year marks the twentieth anniversary of the face-off pitting North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms against the National Endowment for the Arts and Robert Mapplethorpe, who also died twenty years ago this month. Deeming Mapplethorpe’s photography obscene and indecent and seeking to halt an exhibition of his work, Helms helped enact a law that prevented the NEA from using government funds “to promote, disseminate, or produce materials which in the judgment of [the NEA] may be considered obscene, including but not limited to, depictions of sadomasochism, homoeroticism, the sexual exploitation of children, or individuals engaged in sex acts and which, when taken as a whole, do not have serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

Largely in response to this controversy, Dave Hickey began thinking about beauty. Helms, for all his misguided grandstanding, was right—Mapplethorpe’s powerful, disruptive art was obscene, and the art world’s defense of Mapplethorpe obfuscated the role of beauty in the power of art. Far from defending Helms’s action, Hickey, a personal friend of and fan of Mapplethorpe’s, instead sought to refocus the conversation. The result, a little book of only 64 pages, published in 1993, was championed by artists for its forceful call for a reconsideration of beauty—and savaged by more theoretically oriented critics who dismissed the very concept of beauty as naive, igniting a debate that has shown no sign of flagging.

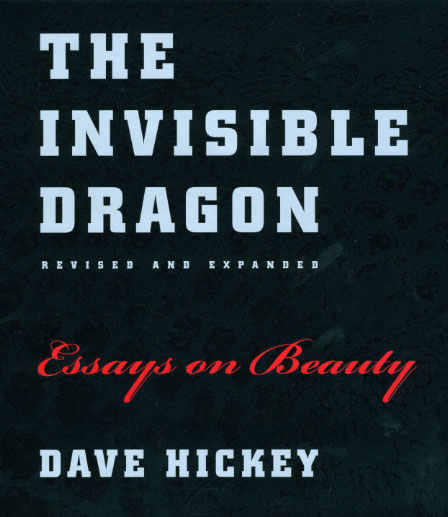

Now, The Invisible Dragon is back. Revised and expanded, Hickey’s controversial book has not mellowed with age. More manifesto than polite discussion, more call to action than criticism, The Invisible Dragon aims squarely at the hyper-institutionalism that, in Hickey’s view, denies the real pleasures that draw us to art in the first place. Deploying the artworks of Warhol, Raphael, Caravaggio, and Mapplethorpe and the writings of Ruskin, Shakespeare, Deleuze, and Foucault, Hickey takes on museum culture, arid academicism, sclerotic politics, and more—all in the service of making readers rethink the nature of art. A new introduction provides a context for earlier essays—what Hickey calls his “intellectual temper tantrums.” A new essay, “American Beauty,” concludes the volume with a historical argument that is a rousing paean to the inherently democratic nature of attention to beauty.

This week, Aimee Walleston of the New York Times interviewed Hickey on the eve of the rerelease. A highlight:

Q: Are you OK with being “the beauty guy” again, for a little while? Seems like there are worse things to be.

A: Why not? For a while, I was simultaneously the “Mapplethorpe guy” and the “Norman Rockwell guy.” I asked myself. “Who would still be a famous artist if the art world disappeared?” I came up with Robert and Rockwell. Whatever is a little off kilter, I’m your guy.

And earlier this month, Newsweek praised the reissue as “both a time capsule of a period when dirty pictures could dismantle institutions and a provocation to reignite the conversation about the purpose of art.” And of course, just as the book remains relevant and incendiary today, so too does its author. “One thing is clear: Dave Hickey still knows how to breathe fire.”