From the Earth to the Moon and back

Where were you on July 20, 1969? Newspapers all over the United States posed this question to readers over the past couple of days, generating hundreds of responses that explain how the moon landing, with its worldwide scale, also had countless much more personal dimensions.

“At that moment I had serious doubts about the relevance of our hard work and the ordering of my personal priorities,” remembers a then-student archaeologist.

“We had the technology to put a man on the moon,” a Vietnam veteran remembers thinking, “yet here I am, dirty and worn out, fighting like it was 1869.”

At the National Review Online, John Derbyshire remembers being at work as a bartender in Liverpool when “in a fragile contraption hurled by a spasm of burning gases across a quarter million miles of empty space (and built, as it happens, less than ten miles from my present home), human beings set themselves down on the surface of another world, in an alien landscape.”

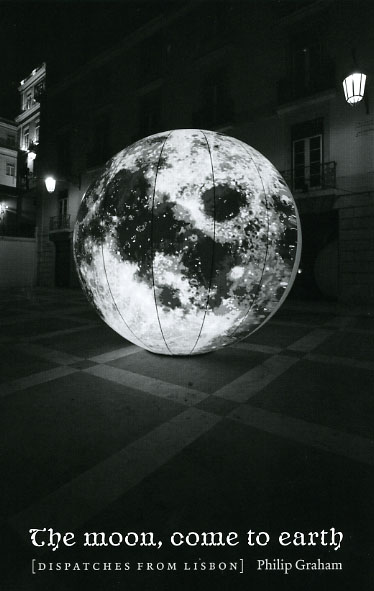

Though the unfamiliar landscape he traverses is a bit closer to home, and though the moon he writes of is artificial, Phillip Graham’s forthcoming The Moon, Come to Earth: Dispatches from Lisbon has more in common with the lunar landing than its title. In the dispatch from which the book takes its name, Graham remembers walking around the city with his daughter and finding

a huge sphere, like a moon, sitting in the corner of a recessed plaza, made of some sort of durable white canvas; it’s lit from within like a giant light bulb, and across its surface are painted stretches of lunar craters and mountain ranges. More than a few of the people passing by stage goofy poses before it, casting themselves as temporary stars of their own remake of E.T.

Perking up, Hannah murmurs, “So pretty.” The moon, it appears, has come to earth tonight, magically, just for her, and even if it has left the shifting clouds behind, Hannah radiates concentration and lines up her shots. I decide to give her all the time she needs, suspecting that my daughter must feel some kinship with this fallen moon. After all, they’re fellow travelers, taken out of context and isolated. I lean back on a stone bench and marvel at just how private public art can be.

Echoing the wonder expressed by those who thrilled to fuzzy-screened TVs forty years ago, Graham illuminates the intensely personal quality of even our most broadly shared experiences, whether they involve a moon we can reach out and touch, or the one that—except in exceptional circumstances—we can only look up at.