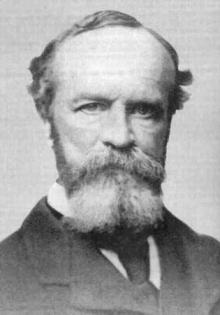

William James, 100 years gone

This Thursday, August 26th, will mark the centenary of the death of William James, and to mark that date the online literary site The Second Pass has declared this William James Week.

In an introductory post, the site’s editor, John Williams, writes,

I read The Varieties of Religious Experience for the first time about four years ago, and I quickly became a James fanatic.… I’ve found since discovering his work for myself that fellow fans share my affection for him, my sense that he is almost a real friend—a remarkable feeling to have for any author, much less one who has been gone for a century.

It’s a feeling that is far from uncommon from those who read James—in many ways he is the opposite of his brother Henry, warm where Henry is cerebral, accessible where Henry is occluded, open and even friendly where Henry is stand-offish. On a recent episode of Melvyn Bragg’s BBC show “In Our Time,” philosopher Jonathan Ree described James in similar terms:

First of all, I think William James is one of the greatest philosophers ever, and he’s untypical. Twentieth-century philosophers, I think, fall into two groups: they’re either nitpicking, pettifogging bureaucrats or else they’re egomaniacs with delusions of genius. [laughter] He wasn’t like that. He was honest, witty, modest, flexible, generous, a very creative, open-minded thinker, and he produced prose which looks as though it was a spontaneous flow of very colloquial thoughts, but is actually incredibly carefully crafted.

If there is such a thing as a lovable philosopher, William James was it.

If you’ve not yet read James, we have a great set of books to get you started. First off is The Writings of William James, a 900-page collection of James’s key writings edited by John J. McDermott. The book features selections from all of James’s major works, plus the entire text of the 1907 edition of Pragmatism. For an outside appreciation of James, it would be hard to do better than Jacques Barzun’s A Stroll with William James, in which the distinguished historian of ideas (who was born three years before James’s death and is still with us) pays what he describes as an intellectual debt to James, commenting on his ideas, his life, and his legacy.

For more on James’s life, you can consult Linda Simon’s biography, Genuine Reality, which the Chicago Tribune described as “essential reading for all soul-searchers,” while for a thorough consideration of James’s ideas, you can check out Francesca Bordogna’s William James at the Margins: Philosophy, Science, and the Geography of Knowledge, which focuses on James’s famously boundary-breaking address to the American Philosophical Association in 1906.

And once you’ve got your James library in order, you can head back over to the Second Pass, where Williams promises excerpts, reviews, and guest posts galore from James fans of all sorts (including, at some point, yours truly). It’s a great opportunity to discover (or rediscover) one of the most perennially fascinating thinkers America has produced.