The Bourgeois Virtues of Mario Vargas Llosa

Writing a pithy sentence about winning the Nobel Prize in literature is an exhaustive experience—what more can be said about this accolade of accolades whose booty (ten million Swedish kroner, or roughly 1.4 million dollars) could alter the life of even the most penniless penner of tales? The background story is well told: nineteenth-century arms manufacturer Alfred Nobel, for whom the prize is named, had the opportunity to read his own obituary, the unfortunately titled “The Merchant of Death is Dead,” eight years before his own death (the piece was meant for his deceased brother Ludvig). This transformative experience of embracing one’s own remembrance spurred Nobel to bequeath his assets via a series of prizes to those organizations and persons “who confer the greatest benefit on mankind.”

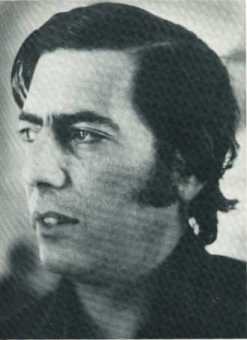

One hundred and ten years later, here we are. This morning, the Swedish Academy awarded the Nobel Prize in literature to Mario Vargas Llosa (odds embraced by L Magazine), Peruvian novelist, journalist, and statesman whose playful approach and political engagement helped him to become one of Latin America’s most acclaimed modernist-realist writers. In recent decades, Vargas Llosa was perhaps most noted for his staunch neoliberal views, including a run for the Peruvian presidency in 1990. Plus, how many writers can claim they gave Gabriel García Márquez a black eye?

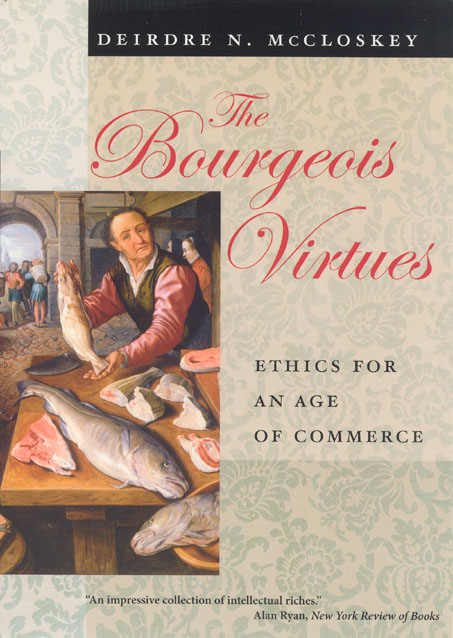

Taking a note from that page, Deirdre N. McCloskey, sage of the history of capitalism, opens The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce by exploring Vargas Llosa’s thoughts on globalization:

Globalization extends radically to all citizens of this planet the possibility to construct their individual cultural identities through voluntary action, according to their preferences and intimate motivations. Now, citizens are not always obligated, as in the past and in many places in the present, to respect an identity that traps them in a concentration camp from which there is no escape—the identity that is imposed on them through the language, nation, church, and customs of the place where they were born.

McCloskey’s sweeping, humorous survey of ethical thought and economic realities takes on more than just Vargas Llosa, spanning from Kant to Bill Murray and back to American economics in a surprising page-turner. While waiting for the sequel Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World to appear from the University of Chicago Press this fall, be sure to check out an excerpt (including nods to Vargas Llosa, Alfred Tennyson, and Chicago-style pizza) from The Bourgeois Virtues online. And no matter your thoughts on the history of capitalism, for more information on Vargas Llosa and his Epic Adumbrations, have a look at a chapter of the same name in Alfred J. Mac Adam’s Textual Confrontations: Comparative Readings in Latin American Literature, which, alongside Vargas Llosa, explores the work of some of Latin America’s most noted writers, including Borges, Neruda, and Arenas.