Conan, can you hear me?

“If that’s art, then I’m a Hottentot.” Oh, bless ye, former President Truman, and your reaction to Abstract Expressionism. We’ve been nursing this line for a few days, as for reasons unknown, we’ve seen a 1995 article by the Independent making the rounds of various Facebook pages and internet listservs. The gist of the reportage? That, amongst other wild revelations, modern art was a “weapon” knowingly used in our cold cultural war with the Soviet Union; that the CIA backed Stephen Spender’s influential journal Encounter; and that a strange beast going by the name the Propaganda Assets Inventory subsidized everything from the 1958 touring exhibition “New American Painting” (featuring de Kooning, Motherwell, and Pollock, in an all-star cast) to the board of directors at MOMA. The rationale of the CIA was, of course, communist-combatant. Up in arms about the appeal communism still had for many intellectuals and artists, the government agency sought to portray Socialist Realism as an outdated art movement, and as the article mentions, they moved boldly forward with that plan:

[A]t its peak [the CIA] could influence more than 800 newspapers, magazines and public information organisations. They joked that it was like a Wurlitzer jukebox: when the CIA pushed a button it could hear whatever tune it wanted playing across the world.

But the pressing question remains: if we couldn’t convince a president of the integrity and value of modern avant-garde movements, did we really convince the rest of the world? And how did the rest of America come to embrace Sunday afternoon trips to a certain midtown Museum or Ed Harris’s later star turn in a related biopic?

Television, duh.

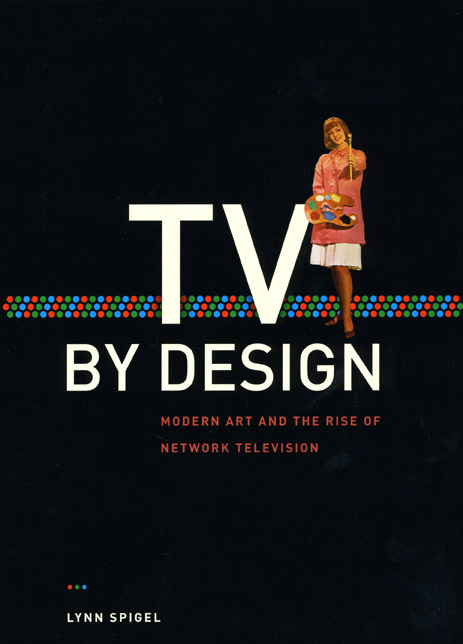

Media art historian Lynn Spiegel penned TV by Design: Modern Art and the Rise of Network Television in order to address the surprising links between the urbane world of modern art and the commercials and network programming that helped define 1950s and ’60s America. From trendy products advertised in between episodes of The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet to the works of Richard Avedon, Ben Shahn, and Ero Saarinen that graced corporate headquarters, company cufflinks, and staged living rooms, Spiegel demonstrates how art, television, and commerce merged in dynamic—and surprising—ways. To read a fascinating excerpt from the book—which tells the story of fine-arts photographer Paul Strand’s experience designing a sponsorship ad for CBS, pay a visit to the book’s UCP website here. Are you listening, Conan? Time to reconsider your sofa.

And what about that Socialist Realism? Did Soviet art movements willingly collapse, eyes a-goggle at Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)? Yes and no, well, not really—art historian, critic, and Our Literal Speed participant Matthew Jesse Jackson tells the most comprehensive story of unofficial postwar Soviet art yet to appear in any language in The Experimental Group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceptualism, Soviet Avant-Gardes. Kabakov’s art—installations, paintings, illustrations, and texts—rose to prominence just as the Soviet Union began to disintegrate and through the work of Kabakov and his Moscow Conceptual Circle peers, Jackson suggests that what emerged in the wake of Stalin is now inextricably part of a transnational art world for which the Soviet Union is largely a memory, fading fast.

Art is what you make it—and both of these books reveal vital contributions to neglected chapters in the history of twentieth-century art. With that in mind, we offer yet another perspective: check out Andy Rooney’s assessment of contemporary public art below. The buck really should stop here: