David Wojnarowicz: The Real Real Thing

We try to start off on the positive side of the street: with congrats to Press authors Matthew Jesse Jackson and Tom Vanderbilt for their Warhol Foundation / Creative Capital Arts Writers grants, which will spear a variety of projects, from art-curio blogging to short-form cultural criticism.

And then we cross—

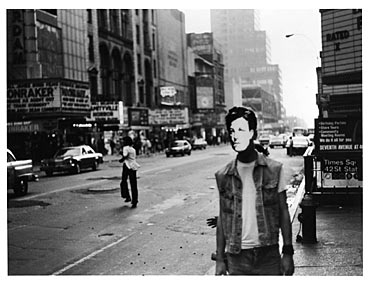

A combination of sources broke the news yesterday about the exhibit “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture,” which opened on October 30th at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. The exhibit, the first at a major museum to focus on “sexual difference in the making of modern American portraiture,” drew some gnarling critique from the Catholic League and conservative politicians, aimed at the late artist David Wojnarowicz’s A Fire in My Belly. Wojnarowicz, a multidisciplinary artist, performer, and activist who died of AIDS-related complications in 1992, is known for work that mixed death and longing, simplicity and pathos. The work in question includes video footage of ants crawling on a crucifix, an image representative of the AIDS crisis. Soon to be Speaker of the House, Rep. John Boehner issued a statement that reads, in part, “American families have a right to expect better from recipients of taxpayer funds.”

The Smithsonian took down the work.

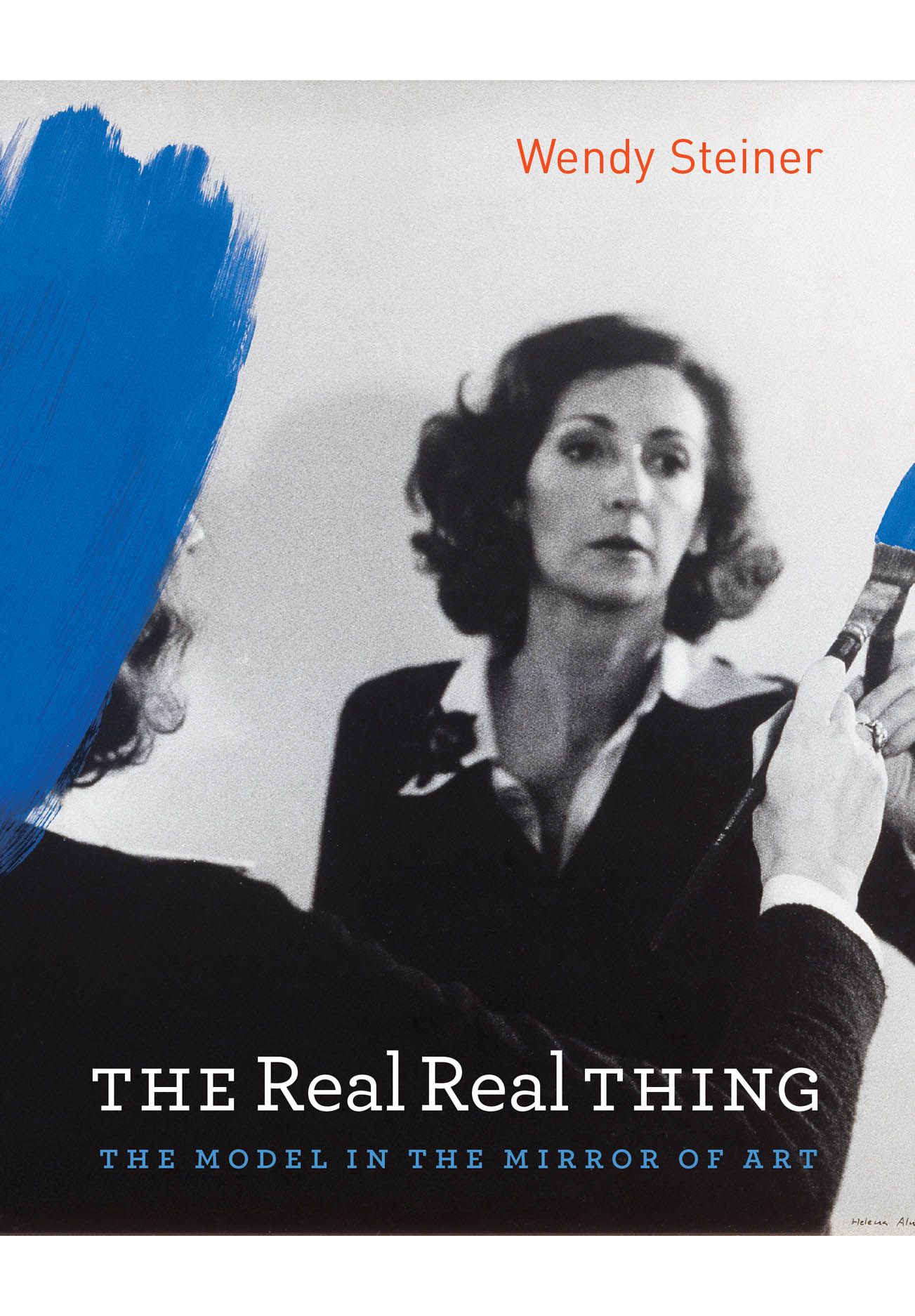

Back to the middle: the explanation. Critic and theorist Wendy Steiner wrote The Scandal of Pleasure: Art in an Age of Fundamentalism in 1995, less than a decade after a fatwa was issue for Salman Rushdie’s death and twenty-five years after Robert Mapplethorpe began snapping his first polaroids. In it, she surveys a wealth of cultural controversies, demonstrating that the fear and outrage they inspire is really the result of an imperiled misunderstanding about the complicated relationship between art and life.

Steiner has always been compelled by these issues and her most recent book The Real Real Thing: The Model in the Mirror of Art is no different. Here she situates our contemporary culture, simultaneously fixated on artifice and the real thing, caught in a media-saturated, real-virtual divide that relies on the arts to etch out a new ethical potential: through the “figure” of the model-protagonist.

In part, it seems like that’s what the Smithsonian curators wanted to do: to draw attention to the difference—imperceptible or obvious—that is all too real. In an excerpt from The Real Real Thing, available on the book’s UCP site here, Steiner describes the changing mores of an almost contemporary society on the cusp of media saturation and anticipates recent events:

A realm of mirrors, of fantasy and feint, the arts have always presented a conundrum in terms of their real-world efficacy. ‘Poetry makes nothing happen,’ declares W. H. Auden in a poem that simultaneously derides that claim. True and not true, the assertion of artistic impotence has been a valid defense against the censor, the bowdlerizer, the book-burner. Do not worry, we assure them: aesthetics and ethics are separate spheres. What ‘happens’ in art is not happening in reality, and so it is quite safe to let anything ‘happen’ there. The changes that take place through art are changes of mind, and democracies recognize the value of entertaining any and all such virtual revolutions.

This position we abandon at our peril, Steiner finishes, before situating modeling—in all of its facets and well, faces—as our best exemplar between reality and representation.

Back to the other side—