Studs Terkel: A Centenary Remembrance

“I love thee, infamous city!”

Baudelaire’s perverse ode to Paris is reflected in Nelson Algren’s bardic salute to Chicago. No matter how you read it, aloud or to yourself, it is indubitably a love song. It sings, Chicago style: a haunting, split-hearted ballad.

Perhaps Ross Macdonald said it best: “Algren’s hell burns with a passion for heaven.” In this slender classic, first published in 1951 and, ever since, bounced around like a ping-pong ball, Algren tells us all we need to know about passion, heaven, hell. And a city.

He recognized Chicago as Hustler Town from its first prairie morning as the city’s fathers hustled the Pottawattomies down to their last moccasin. He recognized it, too, as another place: North Star to Jane Addams as to Al Capone, to John Peter Altgeld as to Richard J. Daley, to Clarence Darrow as to Julius Hoffman. He saw it not so much as Janus-faced but as the carny freak show’s two-headed boy, one noggin Neanderthal, the other noble-browed. You see, Nelson Algren was a street-corner comic as well as a poet.

He may have been the funniest man around. Which is another way of saying he may have been the most serious. At a time when pimpery, licksplittery and picking the poor man’s pocket have become the order of the day—indeed, officially proclaimed as virtue—the poet must play the madcap to keep his balance. And ours.

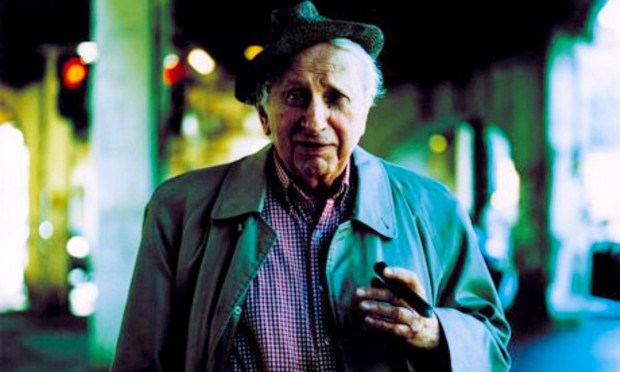

Unlike Father William, Algren did not stand on his head. Nor did he balance an eel on his nose. He just shuffled along, tap dancing now and then. His appearance was that of a horse player who had just heard the news: he had bet her across the board and she’d come in a strong fourth. Yet, strangely, his was not a mournful mien. He was forever chuckling to himself and you wondered. You’d think he was the blue-eyed winner rather than the brown-eyed loser. That’s what was so funny about him. He did win.

A hunch: his writings may be read, aloud and to yourself, long after acclaimed works of Academe’s darlings, yellowed on coffee tables, have been replaced by acclaimed works of other Academe’s darlings. To call on a Lillian Hellman phrase, he was not a “a kid of the moment.” For in the spirit of a Zola or a Villon, he has captured a piece of that life behind the billboards. Some comic, that man.

At a time when our values are unprecedentedly upside-down—when Bob Hope, a humorless millionaire, is regarded as a funny man while a genuinely funny man, a tent show Toby, is regarded as our president—Algren may be remembered as something of a Gavroche, the gamin who saw through it all, with an admixture of innocence and wisdom. And indignation.

—excerpted from Terkel’s Introduction (originally penned in 1982) to the Sixtieth-Anniversary Edition of Nelson Algren’s Chicago: City on the Make

**

It’s impossible to pick a representative interview from the hundreds conducted by Terkel in his lifetime, but this clip from 1961 with James Baldwin, and its opening—Bessie Smith’s Back Water Blues, which Baldwin remarks inspired his “forthcoming novel” (Another Country)—is good enough to take your breath away: