On The Subject of Murder

From the Introduction

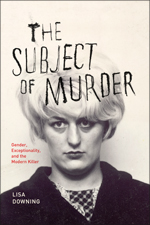

The Subject of Murder: Gender, Exceptionality, and the Modern Killer

by Lisa Downing:

“Serial killers are so glamorized . . . as to tempt other to . . . revere them as the prophets of risk and individual action, in a society overwhelmed and bogged down by the dull courtiers and ass-kissers of celebrity culture.”—(Ian Brady, The Gates of Janus, 2001)

“[Murderers] share certain characteristics of the artist; they know they are unlike other men, they experience drives and tensions that alienate them from the rest of society, they possess the courage to satisfy these drives in defiance of society. But while the artist releases his tensions in an act of imaginative creation, the Outsider–criminal releases his in an act of violence.”—(Colin Wilson, Order of Assassins, 1976)

“Jack the Ripper, along with many of his followers, has achieved legendary status. Such men have become world famous, awesomely regarded cultural figures. They are more than remembered; they are immortalized. Typically, though, their victims, the uncounted women who have been terrorized, mutilated, and murdered are rendered profoundly nameless.”—(Jane Caputi, The Age of Sex Crime, 1987)

As reflected in the epigraphs above—the first written by an incarcerated serial killer; the second by a respected writer, thinker, and murder “expert”—a pervasive idea obtains in modern culture that there is something intrinsically different, unique, and exceptional about those subjects who kill. Like artists and geniuses, murderers are considered special individuals, an ascription that serves both to render them apart from the moral majority on the one hand and, on the other, to reify, lionize, and fetishize them as “individual agents.” And, as the third epigraph by a feminist cultural critic announces, this idealization of the murdering subject needs to be understood in gendered terms. Such discourses, by highlighting the exceptionality of the “individual,” effectively silence gender-aware, class-based analyses about murder. Analyses of this kind might notice which category of person (male) may “legitimately” occupy the role of killer, and which category of person (female) is more generally relegated the role of victim in our culture. Female murderers, by extension, become doubly aberrant exceptions in this culture, unable to access the role of transcendental agency since, as Simone de Beauvoir made clear in 1949, only men are allowed to be transcendent, while women are immanent. From a feminist critical viewpoint, then, the figure of the killer described by Brady and Wilson is not out of the ordinary at all—he is merely an exaggeration, or the extreme logical endpoint, of masculine patriarchal domination, and his othering as “different” serves to exculpate less extravagant exhibitions of misogyny. The ways in which—and purposes for which—murderers are seen as an exceptional type of subject by our culture is the central problem this book seeks to address.

As reflected in the epigraphs above—the first written by an incarcerated serial killer; the second by a respected writer, thinker, and murder “expert”—a pervasive idea obtains in modern culture that there is something intrinsically different, unique, and exceptional about those subjects who kill. Like artists and geniuses, murderers are considered special individuals, an ascription that serves both to render them apart from the moral majority on the one hand and, on the other, to reify, lionize, and fetishize them as “individual agents.” And, as the third epigraph by a feminist cultural critic announces, this idealization of the murdering subject needs to be understood in gendered terms. Such discourses, by highlighting the exceptionality of the “individual,” effectively silence gender-aware, class-based analyses about murder. Analyses of this kind might notice which category of person (male) may “legitimately” occupy the role of killer, and which category of person (female) is more generally relegated the role of victim in our culture. Female murderers, by extension, become doubly aberrant exceptions in this culture, unable to access the role of transcendental agency since, as Simone de Beauvoir made clear in 1949, only men are allowed to be transcendent, while women are immanent. From a feminist critical viewpoint, then, the figure of the killer described by Brady and Wilson is not out of the ordinary at all—he is merely an exaggeration, or the extreme logical endpoint, of masculine patriarchal domination, and his othering as “different” serves to exculpate less extravagant exhibitions of misogyny. The ways in which—and purposes for which—murderers are seen as an exceptional type of subject by our culture is the central problem this book seeks to address.

In Natural Born Celebrities (2005), resonating with Brady’s observation regarding a celebrity-obsessed society to which the figure of the murderer appeals, David Schmid has compellingly described the cult of sensationalist fame enjoyed by the “idols of destruction” that are serial killers in contemporary North America. Where Schmid’s aim is to explore and account for a “specific, individuated form of celebrity” that accrues to the serial killer within that national context, my aim here will be to unpick , both historically and in contemporary culture, the terms “specificity” and “individuation,” rather than the related concept of “celebrity,” that work on and through, and that are exemplified particularly well by, the figure of the murderer. The contemporary, ambivalent idea of the murderer as a special and aberrant subject, and as an object of fascination that can lead to him (and to a lesser extent her) becoming a celebrity, has a history that predates twentieth-century North America, where it is perhaps most prevalently seen today, and that originates in paradigmatically European intellectual ideas.

The ubiquity of the idea of the murderer as a figure of fascination can be testified to by an example from the work of historian of systems of thought Michel Foucault, whose analyses of discourses of criminality and subjectivity will be central to the critical work undertaken in this book, In discussing the case of a rural parricide, Pierre Rivière, who, in 1835, murdered his mother, sister, and brother and produced a long, complex confessional account of his crimes, Foucault reports feeling, “a sort of reverence and perhaps, too, terror for a text which was to carry off four corpses along with it.” Foucault’s team of sociological researchers was drawn to the Rivière dossier as an object of study initially because it was the thickest of all the files they found, but Foucault admits that it held his attention ultimately because of “the beauty of Rivière’s memoir.” He describes the fascination he and his team experienced reading the confessions in the following way: “We fell under the spell of the parricide with the reddish-brown eyes.” This admission of having been mesmerized by the murderer’s confession—and, by extension, seduced by the figure of the murderer himself—is a surprising one for Foucault, an arch demystifier of discourses of individuality, to make. It is a perfect illustration of the widespread and pervasive nature of the problematic that this book seeks to expose and understand.

***

Read more about The Subject of Murder: Gender, Exceptionality, and the Modern Killer here.

(Images, top to bottom: Lisa Downing speaking at The Subject of Murder’s London launch at St. Bart’s Pathology Museum; simulcra-style book cakes at the event courtesy of Lucy Bolton; and Lisa Downing + cake eyes. All photographs by Keifer Taylor.)