Mike Royko: One More Time

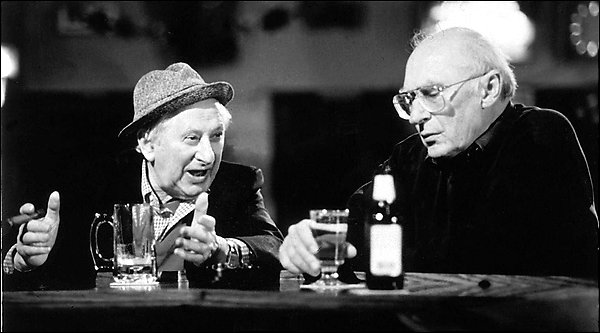

Mike Royko (right), in conversation with Studs Terkel

If you called Chicago home at some point during the second-half of the twentieth century, you probably don’t require an introduction to Mike Royko, or to the work he produced as a columnist for the Chicago Daily News, the Sun-Times, and the Tribune. If you digested these newspapers on a regular basis (you know, as people did before the “reality talkies”), you knew him as a Pulitzer Prize winner with working-class roots, sparse and specific with language, sparser still with pretension, hypocrisy, and corrupt politicking. Royko would have turned eighty-one today—we publish a solid sampling of his work including Early Royko: Up Against It in Chicago, For the Love of Mike: More of the Best of Mike Royko, Royko in Love: Mike’s Letters to Carol, and One More Time: The Best of Mike Royko, from which the excerpt below is drawn. “Ticket to the Good Life Punched with Pain” is later Royko—written just after Rodney King’s beating at the hands of the LAPD and six years before Royko’s premature death at age 64—but a classic example of the writer’s sense of justice and outrage, coupled with an everyday kind of diction that spared no humor or humility, even when framing the dark side of a radically changing America.

So, with a hat tip to Royko, the piece follows below:

March 19, 1991

Ticket to Good Life Punched with Pain

The police chief of Los Angeles is being widely condemned because of the now-famous videotaped flogging of a traffic offender.

But Chief Daryl Gates, while refusing to resign, suggests that the brutal beating might have been an uplifting act that could bring long-range positive results for the beating victim.

As the chief put it at a press conference Monday:

“We regret what took place. I hope he [Rodney King, the beating victim] gets his life straightened out. Perhaps this will be the vehicle to move him down the road to a good life instead of the life he’s been involved in for such a long time.”

I hadn’t thought of it that way, but there could be something in what Chief Gates says.

There’s no doubt that King, 25, hasn’t been an exemplary citizen, although he’s no John Dillinger. When the police stopped him for speeding, he was on parole for using a tire iron to threaten and rob a grocer.

But as Chief Gates said, the experience of being beaten, kicked, and shot with an electric stun gun might be what it takes to “move him down the road to a good life.”

Who knows, in a few years when all of this is forgotten, a reporter might drive out to a nice house in a California suburb and find a peaceful Rodney King pushing a mower across his lawn.

The reporter might ask: “Mr. King, what is it that moved you down the road to a good life?”

“That’s a good question,” Mr. King might reply, “and I’ll be glad to explain it to you. You’ll have to excuse me if I wobble and drool a bit; my face has nerve damage and my coordination hasn’t been the same since they damaged my brain.”

“Of course.”

“But to get back to your question. I think it was after L.A.’s finest hit me about fifty or fifty-five times with their clubs. As you recall, some of the fillings flew out of my teeth and one of my eye sockets sort of exploded.”

“Must have been a tad uncomfortable.”

“Yes. And at that point, I’m pretty sure that those nine skull fractures and internal injuries had already occurred, my cheekbone was fractured, one of my legs was broken, and I had this burning sensation from being zapped with that electric stun gun. I was feeling kind of low.”

“That’s to be expected.”

“Right. But as I was lying there, and they were getting in a few final kicks, and then sort of hog-tying my hands to my legs and dragging me along the ground, I said to myself: ‘Why not try to look at the bright side?'”

“And did you?”

“Yes. I thought: ‘Well, one of my legs isn’t broken; one of my eye sockets isn’t fractured; one of my cheekbones isn’t broken. And although my skull is fractured, my head remains attached to my body; and while fillings have popped out of my teeth, I still have the teeth.’ And I said to myself: ‘Half a body is better than none.'”

“Very inspiring.”

“Thank you. And I had a chance to think about why the police were treating me that way. It was their way of telling me that speeding is an act of antisocial behavior and I had been very bad, bad, bad.”

“You have unusual insight.”

“I try. And I thought that if only I had led the life of a model citizen, this wouldn’t have happened to me. Let’s face it. The L.A. police never fracture the skull of the president of the chamber of commerce, the chief antler in the Loyal Order of Moose, or the head of the PTA. No, it was my past history of antisocial behavior that brought it on.”

“But they had no way of knowing you were on parole.”

“Yes, but I’m sure they could guess just by the look of me. Be honest, I don’t look at all like the head of the PTA, do I?”

“True.”

“Then, later, when Police Chief Gates said that the beating, although regrettable, could be the vehicle that would get me on the road to the good life, everything became clear. I realized that the beating would turn my life around and be a one-way ticket to the good life.”

“The chief’s words inspired you?”

“Not exactly. To be honest Chief Gates’ words convinced me that he had to be as dumb an S.O.B. as ever opened his mouth at a press conference.”

“But you said he helped you to a good life.”

“That’s right, he did.”

“How?”

“When I took his police department to court, that jury awarded me a couple of million in damages, and I’ve been leading the good life ever since.”

“I don’t think that’s what the chief had in mind.”

“I don’t think that chief had anything in mind.”