Andrew Piper on the new world of electronic reading

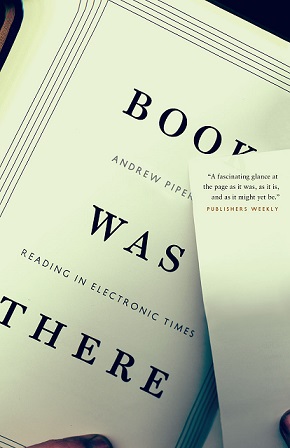

In 2012, Andrew Piper published Book Was There: Reading in Electronic Times, which expanded upon his established interest in textual circulation, embodiment, and identity (see Dreaming in Books: The Making of the Bibliographic Imagination in the Romantic Age) under the pressures of the digital. Since then, in a year that has evidenced the e-book’s continuing encroachment into the literary market share (from 20 percent in 2012 to early estimates of 30 percent in 2013), Piper has upped the stakes of his argument: we have already gone electronic, and it’s only because of our own constraints that we still make e-books look and act like printed books. If we know that “literature is data,” how can we poise ourselves to take much greater advantage of that knowledge amid semi-seismic technological shifts?

In a recent essay for World Literature Today, Piper considered the case for computational reading: a way of translating literary texts into quantifiable units—rather than simply mirroring them as the printed book’s shadow self—that can be used for purposes such as determining the authorial identity of Elizabethan authors or sussing out whether late-career works by Agatha Christie reveal symptoms comparable to those found in Alzheimer’s patients. Piper, whose own recent work explores the history of the modern novel in relationship to narratives of conversion, notes that it is the unique category of literature that has the most to offer in terms of understanding correlation, repetition, exception, and granularity in language. As he notes in the essay (shortly after comparing the e-book to a “gated community”):

Skimming, holding, sharing, annotating, and focusing—these are just some of the many ways that e-books diminish our interactions with books. And yet they remain the default way we have thought about reading in an electronic environment. E-pub or Kindle, it doesn’t really matter. We have fallen for formats that look like books without asking what we can actually do with them. Imagine if we insisted that computers had to keep looking like calculators.

Escaping this rut will require not only a better understanding of history—all the ways reading has functioned in the past that have yet to be adequately re-created in an electronic world—but also a richer imagination of what lies beyond the book, the new textual structures (or infrastructures) that will facilitate our electronic reading other than the bound, contained, and pictorial objects that we have so far made available. Instead of preserving the sanctity of the book, whether in electronic or printed form, we need to think beyond the page and into that all too often derided thing called the data set: curated collections of literary data sold by publishers and made freely available by libraries. This is the future of electronic reading.

Though provocative, it’s difficult to argue with Piper’s basic premise: as we’ve said before (and as Walter Benjamin and Marshall McLuhan have said before us), media often already contains within itself its logical replacement—such is the interrelationship between art and the development of technology under capitalism. While we are busy mourning for all that the e-book doesn’t possess—handwritten marginalia, annotation, and dog-eared pages among them—mass culture’s mediumship has already moved on to desiring other modes of communication more in kind with (i.e. generated by) the technological provisions of the present day.

This progression, whether natural or not (not an argument undertaken here), is an unavoidable future. What Piper polemicizes—that “texts aren’t static pictures”—could be interpreted as a truism similar to the realization that the landmark speeches of nineteenth-century oratory had life to offer beyond their auratic delivery at the same time as they pointed toward the burgeoning development of sound recording technology.

As Piper concludes, “Words aren’t everything. But they are too important to bury in a pretty picture.”

Read more about Book Was There here.

Read Andrew Piper on algorithmic and computer-generated writing in a recent book review here.