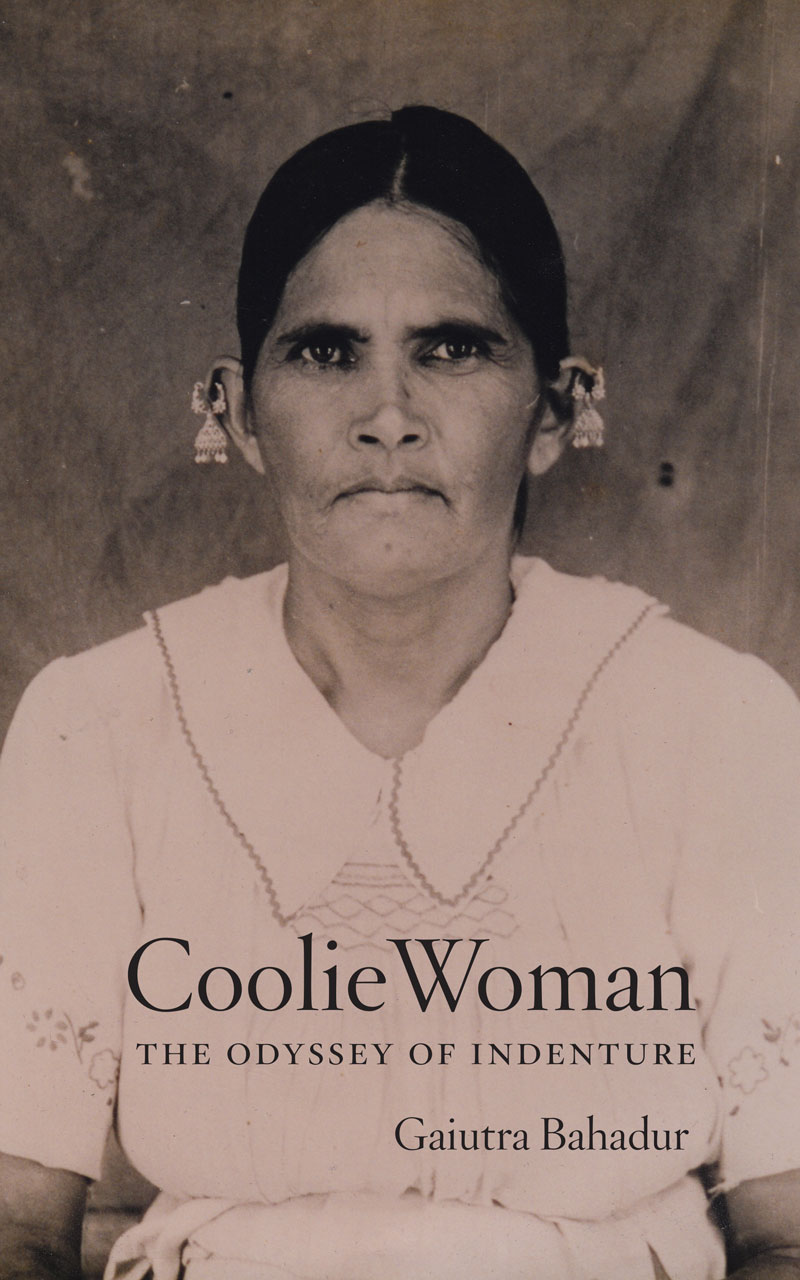

Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture

Gaiutra Bahadur’s Coolie Woman addresses the repressed history and forgotten odysseys of this marginalized group of colonial women—runaways, widows, and others who, as indentured servants, replaced newly emancipated slaves (slavery was abolished by the British Empire in 1833) on sugar plantations around the globe. Recent profiles of Bahadur discussing the book’s subject matter have appeared at the Guardian and The Writer’s “How I Write” series. For Bahadur, the story is personal; through mining the archives of these women’s stories, well as digging up her own roots, she encounters her great-grandmother’s own traumatic “middle passage” from India to Guyana in 1903.

Gaiutra Bahadur’s Coolie Woman addresses the repressed history and forgotten odysseys of this marginalized group of colonial women—runaways, widows, and others who, as indentured servants, replaced newly emancipated slaves (slavery was abolished by the British Empire in 1833) on sugar plantations around the globe. Recent profiles of Bahadur discussing the book’s subject matter have appeared at the Guardian and The Writer’s “How I Write” series. For Bahadur, the story is personal; through mining the archives of these women’s stories, well as digging up her own roots, she encounters her great-grandmother’s own traumatic “middle passage” from India to Guyana in 1903.

“I found out that her story was extraordinary but it wasn’t exceptional in that most of the women who went to West Indies as indentured laborers were like her, they were by themselves” says Bahadur. “What motivated me to write this story was to sort of rescue them from anonymity if I could. To give them names.”

For many of these women, as Bahadur conveys in her recent appearance on NPR’s Tell Me More, their journeys were only the start of life marked by widespread and blatant oppression: upon arrival, they were met with hard labor, sexual exploitation, violence, and the rescinding of basic human rights.

The title of Bahadur’s book is charged with this legacy of colonial exploitation, and like the personal histories for which it performs an advocate, it occupies a borderland between freedom and slavery, truth and slur.

From the Preface:

“Coolie” may bare a jagged edge, like a broken bottle raised in threat. But it also ricochets still down dirt lanes in the Guyanese village where I was born, in far more complicated ways, in greetings that are sometimes menacing but also often affectionate and intimate, signifying a sense of shared beginnings. Much depends on who is using the word and why. I have chosen to employ it because it is true to my subject. My great-grandmother was a high-caste Hindu. That is a fact. But she left India as a “coolie.” That is also a fact. She was one individual swept up in a particular mass movement of people, and the perceptions of those who controlled that process determined her identity at least as much as she did. The power of her colonizers to name and misname her formed a key part of her story. To them, she was a coolie woman, a stock character possessing stereotyped qualities, which shaped who she was by limiting who she could ever be. The word coolie, in keeping with one of its original meanings, carries this baggage of colonialism on its back. It bears the burdens of history.

To read more about Coolie Woman, click here.

To listen to Bahadur’s full-length interview on NPR, click here.

To read another interview with Bahadur at the New York Times, click here.