In conversation: Molly Haskell and Matt Zoller Seitz

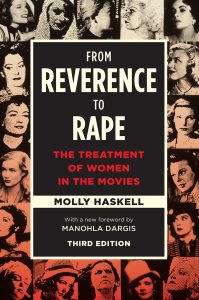

Molly Haskell’s From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies is now in its third edition (accompanied by Manohla Dargis’s new foreword)—and the classic work of feminist criticism remains as urgent as when it was first released, crucially analyzing not only images of women in movies, but also the relationship between these images and the status of women in society, the stars who fit these images or defied them, and the attitudes of their directors. Below follows an excerpt from an interview between Haskell and critic Matt Zoller Seitz, wherein the two revisit the book.

***

MZS: One of the things that fascinates me about From Reverence to Rape is that, in addition to being about what it’s about—the image and treatment of women throughout movie history—the book is also about what’s shown and what’s withheld, what’s said and what’s unspoken, and what effect that all has on the viewer. At times it seems as if you think that a bit of repression can be good for movies.

MH: I do. Well … it’s really plus and minus.

Last night I was watching “North by Northwest” and I thought, “That can’t be done anymore.” They can’t make films that have that kind of subtext, and I guess it’s because we don’t have the veneer of normalcy that that sort of movie depends on, or the veneer of oppression and everything else. But those scenes with Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint are so erotic, and also when he’s hating her. Do you remember the film?

Vividly.

OK, so after he’s almost been killed by the crop duster and he comes to her room, and he doesn’t tell her that he knows she’s behind it, it’s all there. But it’s—so full of hate and the hate is so close to eros that it’s just indistinguishable! So amazing! I don’t think there’s anything like that today.

I did a Q&A with Ed Sorel, who’s done this book on Mary Astor, with his cartoon drawings and everything, it’s just fabulous. Well, we were talking about “Dodsworth” and how sophisticated it is. It’s such an adult movie, because you know Ruth Chatterton is having affairs with all these people, but the movie doesn’t spell it all out. You see her go to her room, and you know it. And people were amazed by that because they knew how strong the Production Code was at that time in the Hays Office.

Ed said that was what was wrong with the movie of “The Maltese Falcon,” you needed to know that Humphrey Bogart and Mary Astor had gone to bed together. Do you think they went to bed together?

Oh, sure. I saw the movie for the first time before I read the novel and I just assumed they’d had sex. I think there’s something in the way they behave. Don’t you?

Oh yeah, absolutely.

Although now that you mention it, I guess the movie never comes right out and says they had sex.

It doesn’t, but you infer it. In that scene in “North by Northwest” with Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint in the train compartment, you know they’re going to do it for sure because they’re actually together in the same room, so there’s more of a lead-in to it. But you infer that, too.

You know, Andrew [Sarris] didn’t like the Code, he thought it was stifling in so many ways, and that it was ridiculous with all the happy endings and so forth. But there were ways in which movies made under the Code were more imaginative about relations between men and women.

Well, then, I want to read something to you. This is a passage that survived all the different editions of From Reverence to Rape, and it discusses this idea that movies became more “sophisticated” in the 60s and 70s: “We’re lost in our freedom, longing to feel urgency and necessity, the preciousness of time and love and light, the irrecoverableness of a decision. But when anything is possible, nothing is special.” And then you write:

“Women have grounds for protest, and film is a rich field for mining the female stereotype. At the same time, there is a danger of going too far the other way, of grafting a modern sensibility onto the past so that all film history becomes grist in the mills of outraged feminism. If we see stereotypes in films, it is because stereotypes exist in society. Too often we look at roles from the past in light of liberated positions that have only recently become thinkable.”

Well that’s more true today, I think.

Orson Welles and all these people said they didn’t like sex scenes because it absolutely broke the illusion or atmosphere or line about whatever’s going on. Character stops, plot stops, and you’re looking at bodies.

***

To read more about From Reverence to Rape, click here.