Passchendaele, a century on

“Why should I not write it?”

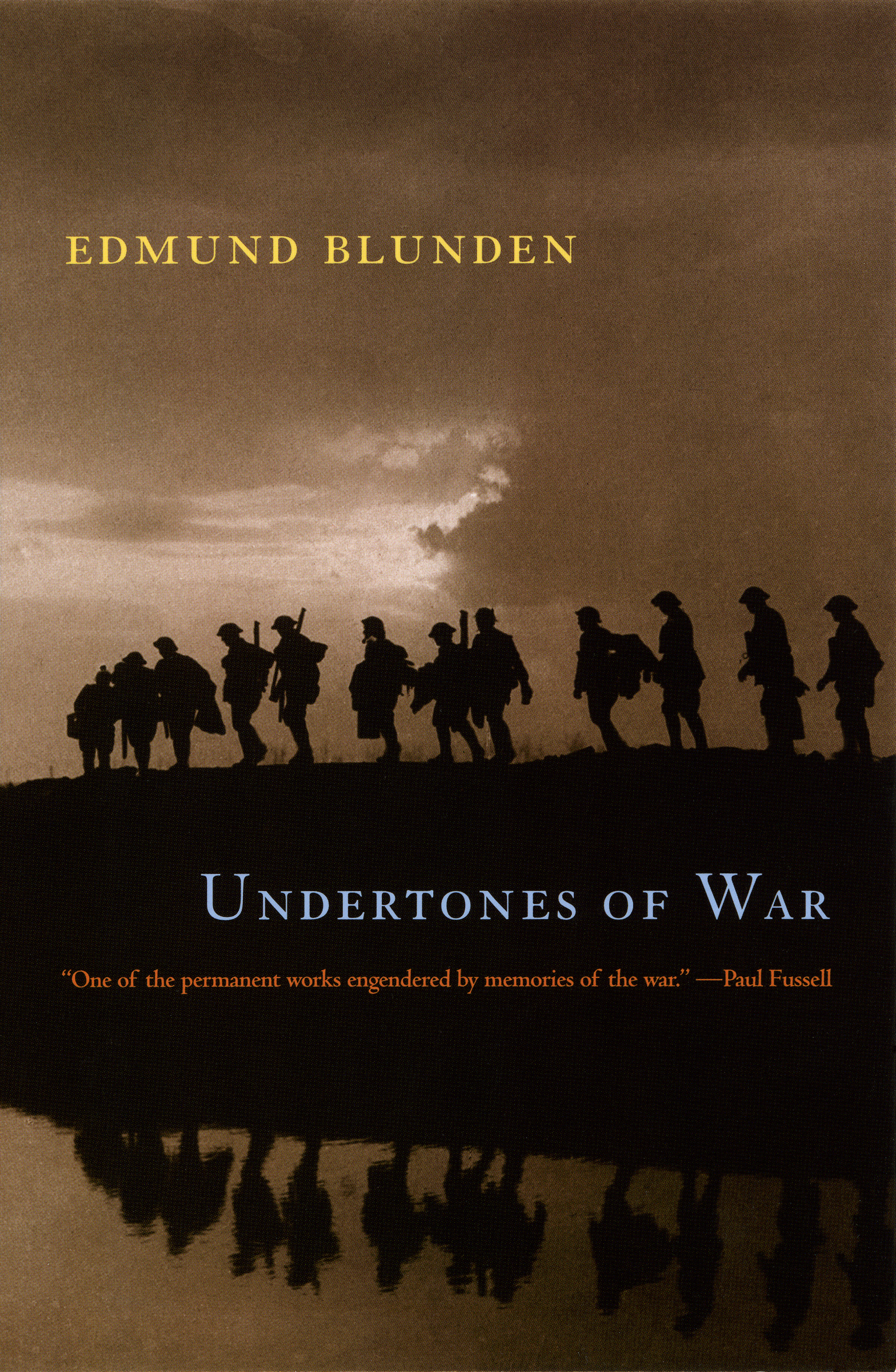

That’s Edmund Blunden, opening his now-classic memoir of World War I, Undertones of War, in 1928. Blunden, a poet, joined the Royal Sussex Regiment in 1915, and he served in a number of major battles of the war, including Passchendaele, which began July 31, 1917 and would continue–at a cost of nearly 600,000 dead–until November 10.

Blunden’s book was one of a number published a decade or so after the war that both marked and brought about a change in English opinion about the war and its legacy. William Manchester, in The Last Lion, wrote,

The most extraordinary thing about England’s disenchantment with the war is that it didn’t surface for over ten years. The reading public had been fed the self-serving memoirs of those responsible for the disaster and the thin fictional gruel of Bulldog Drummond and Richard Hannay. Those who had remained home were simply incapable of absorbing the truth. Aging Tommies told them that sixty thousand young Englishmen had fallen on the first day of the battle of the Somme without gaining a single yard. Sixty thousand! It couldn’t be true. Those who said so must be shell-shocked.

But by 1929, after the publication of Undertones, Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of an Infantry Officer, Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That, and, from the other side, Erich Garcia Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, public understanding of the war had changed, permanently, and in a way that would powerfully affect English thinking in the slow run-up to World War II.

“I must go over the ground again,” Blunden wrote. He did it for himself, and for his fellow soldiers; it affected everyone.