It’s Independence Day! Read an Excerpt from “Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose”

In the years after the Revolutionary War, the fledgling republic of America was viewed by many Europeans as a degenerate backwater, populated by subspecies weak and feeble. Chief among these naysayers was the French Count and world-renowned naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, who wrote that the flora and fauna of America (humans included) were inferior to European specimens.

Thomas Jefferson spent years countering the French conception of American degeneracy. The American moose, which Jefferson claimed was so enormous a European reindeer could walk under it, became the cornerstone of his defense. Convinced that the sight of such a magnificent beast would cause Buffon to revise his claims, Jefferson had the remains of a seven-foot ungulate shipped first class from New Hampshire to Paris. Unfortunately, Buffon died before he could make any revisions to his Histoire Naturelle, but the legend of the moose makes for a fascinating tale about Jefferson’s passion to prove that American nature deserved prestige.

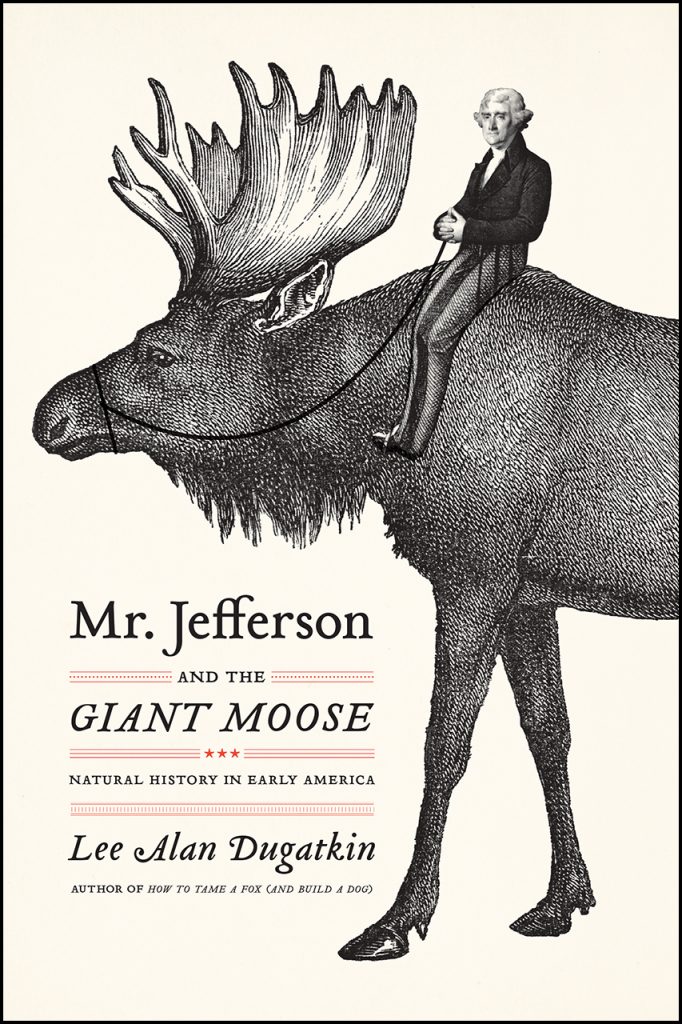

In Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose, first published in 2009 and reissued in paperback this year, Lee Alan Dugatkin vividly recreates the origin and evolution of the debates about natural history in America and, in so doing, returns the prize moose to its rightful place in American history. Read on for an excerpt from chapter six:

Enter the Moose

Though Notes on the State of Virginia was his only book, Jefferson’s writings—especially his correspondence—were prolific, and show him to be the quintessential man of ideas and thought. But Jefferson also understood that in order to convince, you sometimes need to go with the tangible—things that people can hold, touch, feel, and smell. This approach would serve him well in the argument over degeneracy.

While serving in France, Minister Plenipotentiary Jefferson planned to personally hand the great naturalist Buffon proof that American life was not inferior to that in the Old World—and that proof would come in the form of a seven-foot-tall moose. Jefferson could be only hesitantly optimistic that this strategy would work. Twice before, Buffon had been given physical evidence that his images of life in the New World were incorrect. His responses on those occasions did not bode well for Jefferson’s plan to use the giant moose to persuade the Count to recant his degeneracy hypothesis.

The first pre-moose incident occurred just before Jefferson was to sail off to his ministerial post in France. Jefferson had long suspected that Buffon had mislabeled the American panther as the cougar in Natural History. Buffon had claimed that the panther was found in Africa and the East Indies and possessed “a ferocious air, a restless eye, a cruel aspect, brisk movements . . . has a rough and very red tongue, strong and pointed teeth, hard sharp claws, a beautiful skin.” Cougars, on the other hand, which Buffon initially thought were restricted to South America, but then learned were in North America (as black cougars), were less impressive: “their skin is so tender as to be easily pierced by the simple arrows of the Indians. . . . Neither the jaguars nor cougars are absolutely ferocious. . . . They despise the assaults of dogs, whom they often seize in the very neighbourhood of houses. When pursued by such a number of dogs as obliges them to fly, they take refuge in the trees.”

Jefferson was certain that the cougar that Buffon had identified in America was in fact a black panther, as panthers so often killed sheep and wreaked general havoc that bounties were offered for them and reported in newspapers such as the New York Journal, the Boston Gazette, and the Charleston Morning Post. An opportunity for Jefferson to get his hands on evidence that he could use to make the case that the panther was indeed found in America arose in May 1784, when Jefferson and his daughter Patsy stopped in Philadelphia en route to boarding a France-bound ship from Boston. As Jefferson recalled the story: “I observed an uncommonly large panther skin, at the door of a hatter’s shop. I bought it for half a Jo on the spot, determining to carry it to France to convince Mons. Buffon of his mistake with relation to this animal: which he had confounded with the Cougar.” It would take some time, however, before Jefferson would be able to present both his argument and his panther skin to Buffon. In October 1785, more than year after arriving in France, Jefferson wrote that he had “never yet seen Monsr. de Buffon,” which is not all that surprising given that Jefferson was stationed in Paris, while Buffon spent a great deal of time at his family estate back in Montbard.

At last, in the first few days of 1786, Jefferson got his chance to meet the Count in person, when Buffon offered to host a dinner for Jefferson and the Marquis de Chastellux. Jefferson had sent the panther skin to Buffon before the dinner—indeed receipt of the panther skin seems to have spurred the dinner invitation—and he talked with Buffon about this creature during his dinner visit. He remembered Buffon as “a man of extraordinary power in conversation,” and at the dinner, Jefferson presented his case for the panther. The Count was gracious, and after listening to Jefferson’s arguments, “he acknowledged his mistake.” At the same time, Buffon gave no indication of revising his general assessment of North American life, let alone his ideas on degeneracy.

On the surface, Jefferson’s wish that Buffon admit his error about the panther seems picayune—more a display of Jefferson’s interest in the minutiae of taxonomy than an issue relevant to the argument about North American degeneracy. It is true that the Count painted a more noble picture of the panther than of the cougar, but there is no evidence that Jefferson thought the panther vs. cougar argument was especially relevant to Buffon’s claims about degeneracy. What this episode demonstrated, though, was that Jefferson would go a long way to prove Buffon wrong. Voyages across the Atlantic were lengthy and arduous, and people were careful to take with them only their most valued possessions. Yet in the tumult of preparing to go from Philadelphia to Paris, Jefferson thought it important enough to take time to stop at a hatter, buy a panther skin, and carry it on board—all to make a point with Buffon.

Having Buffon admit his error was so significant an event that Jefferson was still telling the story to Daniel Webster more than forty years later. The whole affair was an attempt to demonstrate to Buffon, and others who would one day read of it in Jefferson’s correspondence, that the Count didn’t know his North American animals particularly well. And if he was wrong about panthers and cougars, then his credibility was all the lower when it came to major issues like American degeneracy.

The second pre-moose instance—wherein Jefferson encountered in Buffon a man who seemed to refuse to budge, even in the face of physical evidence—revolved around the “mammoth” discussed in Notes on the State of Virginia.

In the summer of 1705, a Dutch farmer unearthed a huge tooth weighing nearly five pounds on the grounds of Claverack Manor, near Albany, New York. The tooth was sold to Albany assemblyman Peter van Bruggen for a half a pint of rum, displayed before the assembly, and eventually given to the royal governor of New York, who shipped it off to the Royal Society in a box marked “tooth of a giant.”

More bone fragments of this giant creature were soon found around the original site, and the news spread. Congregationalist minister Edward Taylor, whose grandson Ezra Stiles would become president of Yale University and an important figure during the Revolutionary War period, had seen the bones for himself, and he believed that they were the remains of a “monster” that he judged to be above “60 or 70 feet high.” Taylor even composed a poem about the so-called “giant of Claverack:”

His Arms like limbs of trees twenty foot long,

Fingers with bones like horse shanks and as strong

His thighs do stand like two vast millposts stout.

Soon the American colonists, as well as others interested in these remains, were engaged in the first debate about the Claverack monster—were these the remains of a race of giant humans, or some giant animals?

While some prominent figures, such as Cotton Mather, held that the bones were those of the giants of the Old Testament—giants that had perished in Noah’s flood—most believed them to be the remains of some terrible animal akin to that described in Taylor’s verse. This argument continued for many years, but the point became moot in 1728 after a pair of Royal Society papers that were based on comparative anatomy demonstrated that the remains were clearly those of some giant animal—an animal that would play a role in the American degeneracy argument.

Interest in the remains of this giant Claverack creature grew when news that prisoners who had been exiled to Siberia by Peter the Great had uncovered similar fossil remains thousands of miles away. The Russians spoke of these remains as those of a “mammut” or mammoth. Soon the colonists were using this term to describe their findings as well, although many referred to the mysterious creature whose bones had been uncovered as the incognitum—a term derived from the Latin for “unknown.”

More and more bones of the incognitum were uncovered in the years following. Perhaps the most important of these were the 1739 remains uncovered at a salt lick—called the “Big Bone Lick”—in what would eventually become the Commonwealth of Kentucky. This salt-lick site became the major source of mammoth bones in the colonies—Benjamin Franklin had four ivory tusks, a molar, and three vertebrae from the site—with bones being unearthed there well past the American Revolution. So many fossil remains were uncovered at what soon became known as “Big Bone,” that a sample of mammoth bones was eventually shipped to Paris—bones that became the focus of another argument between Buffon and Jefferson.

As the number of fossil remains grew, so too did the legend of the incognitum. Its sheer size, and the very notion that something that big roamed North America, led many colonists to believe that this was a fierce creature, and that image carried immense power. Eventually the mammoth was painted as a killer of enormous proportion, capable of apocalyptic actions: “Forests were laid waste at a meal, the groans of expiring animals were everywhere heard,” read one description, “and whole villages, inhabited by men, were destroyed in a moment. “Although that depiction did not appear until 1801, Thomas Jefferson understood the power that the incognitum represented twenty years earlier, both when writing Notes on the State of Virginia, and during his time in Paris. Such a creature could play a role in debunking the degeneracy claim. If Buffon accepted that the mammoth—the largest terrestrial creature ever described at the time—had roamed North America, how could its existence be squared with his degeneracy argument?

The bones from the Big Bone Lick that were sent to Paris became part of Buffon’s Royal Cabinet of Natural History, and the Count himself examined these samples. He first mentioned both the American and Siberian samples in a rather unexpected place—toward the end of his 1761 description of lions and tigers in volume 9 of Natural History. There Buffon wrote of his “astonishment” at these creatures that dwarfed the elephant, but which “no longer exist.” Buffon’s views—both of a new species, distinct from the elephant, and of the extinction of this species—would vacillate over time. But, at that moment, Buffon argued not only that the mammoth was extinct, but that extinction might be common: “How many smaller, weaker, and less remarkable species must likewise have perished, without leaving any evidence of their past existence?”

Buffon’s collaborator, the world-famous anatomist Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, examined the remains of the mammoth sometime after the Count’s reference to its extinction. By comparing the Big Bone Lick bones (as well as the bones of the Siberian mammoth) with those of the elephant, he found no significant differences, and concluded that the mammoth was nothing more than a large—albeit very large—elephant. Daubenton, however, recognized one flaw in his theory. While the bones matched those of the elephant, the teeth from the lick did not neatly match an elephant’s “grinders.” He concluded that the teeth (grinders) were those of a hippopotamus that had died in the same area, and were incorrectly lumped in with the elephant bones. Such a mistake would be easy for Daubenton to imagine, as it was well known that many of the bones at Big Bone Lick were collected by Indians, and the theory of degeneracy would suggest that with such savages doing the collecting, errors were bound to occur.

Buffon next took up Daubenton’s position and made it explicit in his 1764 Natural History (volume 11) entry on the elephant. From Daubenton’s observations, Buffon noted, “we cannot doubt that those tusks and bones we have already noticed for their prodigious size, actually belonged to the elephant. . . . Daubenton is the first who has proved them unquestionable by exact measures and comparisons, and reasons founded on the great knowledge that he has acquired in the science of anatomy.” So while Buffon made it clear that America presently had no elephants, he accepted that they had once roamed that land. Then, in a second turnabout, in 1778, Buffon used his Epochs of Nature to return to his original position on extinction. New evidence on jaw and tooth structure led Buffon to claim that the American and Siberian bones represented two different species, distinct from the elephant, and both extinct. He named the American species the American mastodon. Indeed, George Gaylord Simpson, one of the twentieth century’s leading experts on fossils, has argued that the whole debate around the bones of the mammoth and mastodon marked the birth of some of the tenets of modern paleontological thinking.

Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose is available now! Find it on our website, online at any major booksellers, or at your local bookstore.

Lee Alan Dugatkin is an animal behaviorist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science in the Department of Biology at the University of Louisville. He is the author of more than a 150 papers and author or coauthor of many books, including, most recently, How To Tame a Fox (and Build a Dog), also published by the University of Chicago Press.