By Way of Beginning: Read an Excerpt from “Dark Lens” by Françoise Meltzer

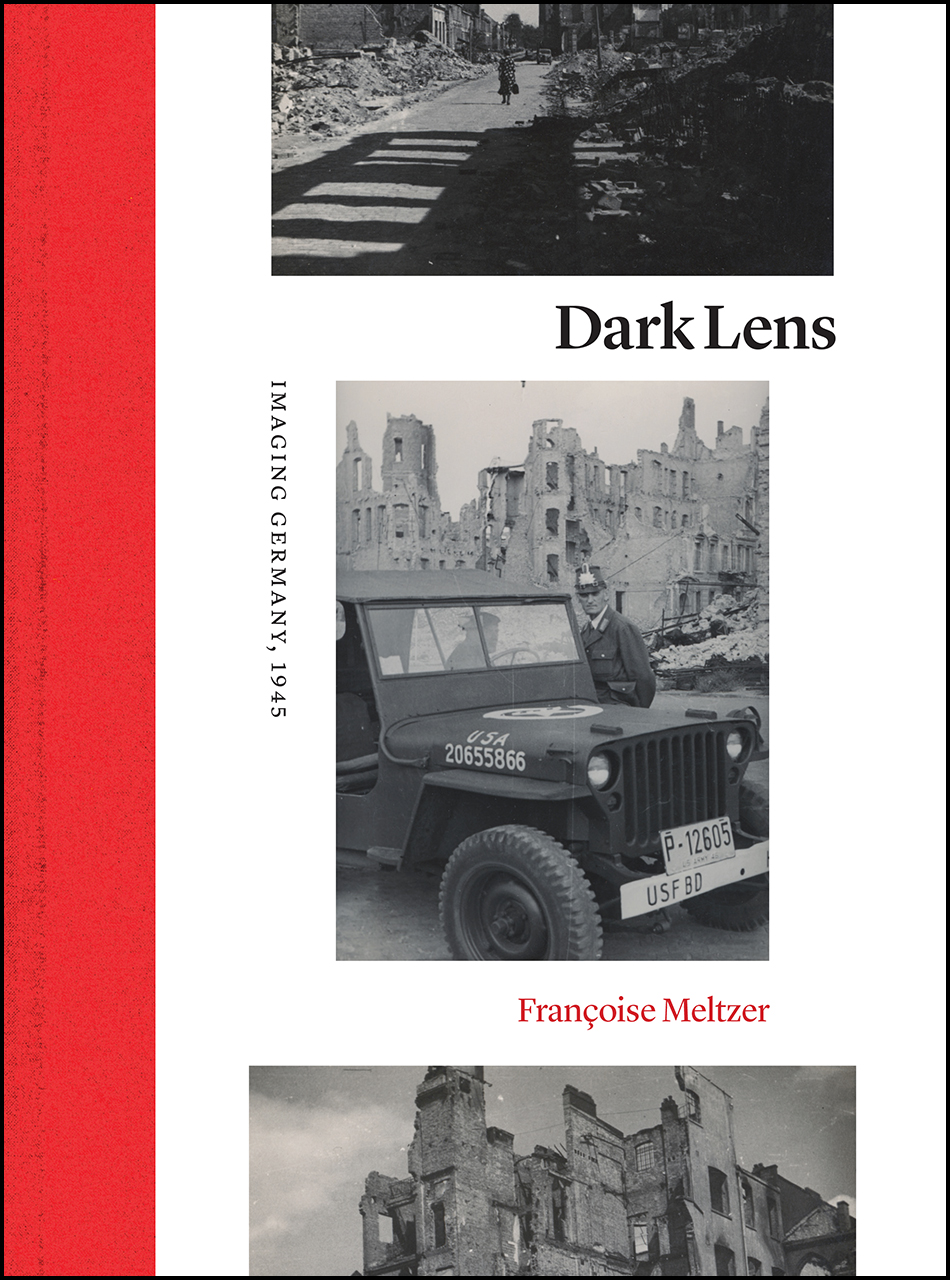

The year 2020 will mark seventy-five years since the Second World War came to an end. In her new book, Dark Lens: Imaging Germany, 1945, Françoise Meltzer draws on her childhood memories of post-war Germany to consider how we construct our memories of war. Analyzing a collection of photographs taken by her mother, Jeanne Dumilieu, Meltzer confronts the ruins, wreckage, and ghosts that the war left behind.

My mother, who was French, had been in the Resistance in Paris during the war. I never learned this from her (I found out from her friends, and by accident, in my late twenties); nor did she speak much about the occupation of Paris. The only thing she talked about was how hungry she and the Parisian population were throughout the war. When I asked her why she had never told me that she was in the Resistance, she retorted with some contained anger, “Today, everybody was in the Resistance. I have nothing to say about it.” But it must be said that this was a particularly tight-lipped generation: my father never spoke of having been in the London Blitzkrieg, nor my uncle of surviving Buchenwald, nor my aunt of having hidden my mother, and thus having put my aunt’s own life in jeopardy. I found out after my mother’s death that she hid from the Gestapo for six weeks in a cellar. My cousin Jean-Claude, only eight years old in 1943, left for school every day with a package. He was instructed, with no explanation given, to drop the package, without stopping, in the window well of the cellar where (unbeknownst to him) my mother was hiding. He never learned until years later what he had been delivering nor why; it was food and water.

My mother married my father, an American, in 1945. He was in the State Department and serving in France. But upon marrying, he had to leave that country, given that his wife was a French national and thus posed a security risk—she might be a spy. He was thus transferred to Germany. My mother consequently found herself living in Berlin amid a population and in a country that she detested. Moreover, State Department rules stipulated that the wives (there were, after all, no State Department husbands then) were not permitted to work. Unhappy at being forbidden to work (she had had a successful career as a business woman in France), she told me that she began taking photographs to keep herself busy, and because the ruins were so portentous a presence, everywhere around her. She also said this: that the entire time she photographed the ruins, she was constantly torn between a feeling of “Serves you right, bastards!” and a profound humanitarian response to the suffering of which the ruins were stark witnesses. Photographing the devastation, she said, was completely exhausting, precisely because of these extreme, conflicting responses.

Though I was born several years after the war, I, too, along with many other German children, grew up playing among the ruins. Like Joel Agee,2 I remember seeing the remnants of staircases, different wallpaper for various (and now open) rooms, lighter patches on the wallpaper where a picture had hung, ripped-apart plumbing, hanging wires, and broken pieces of furniture. The ruins were for me an enticing playground, though I remember once seeing a dead man who had hanged himself, with a handwritten sign pinned to his chest. An older boy, who could read, told me it said, “I am hanging here because I could not feed my wife and children.” Another man was removing the dead man’s shoes, and then put them on his own feet. The “playground” could be sinister indeed.

Ruins were thus the scenery, as it were, of my childhood. When we landed in New York Harbor in 1956, the first question I asked my mother was, “Where are the ruins?” I could not imagine a world without them. The present study on the description of such ruins, then, is deeply embedded in my personal history. It is a book I came to realize that I had to write—no doubt to come to terms with these stark images of my childhood, which have never receded. My hope is that the issues this study raises, however, triggered though they have been by my past, transcend the personal and begin to probe the question of how to image catastrophe, and what it means to target civilians in war—any civilians. Clearly, this is a particularly pertinent question in our present era of drones, suicide bombers, smart bombs, rockets, terrorist attacks, nuclear missiles, and any number of other highly sophisticated devices and undertakings intended for the specific purpose of killing civilians.

I have remarked here that my mother’s generation was tight-lipped—most of them did not talk much about their war experience. Some of my readers, when this book was still in manuscript, noted an uncharacteristic stylistic reticence of my own. I have come to realize that such reticence on my part is symptomatic of what Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok call “transgenerational haunting.” I am indeed haunted by the generation that witnessed these events—the events on all fronts of World War II—of which this book examines only a very partial aspect; and I seem here to have inherited some of that generation’s reserve.

I have tried to overcome this discomfort, or restraint, by including a few childhood memories at the outset of this study. But my point in producing these is not primarily autobiographical; rather, it is to convey the atmosphere of a devastated Germany, as experienced by a child. There was much that I did not understand, but also much that I continue to carry with me. I have tried to choose memories that tell at least as much about the time, about the feel of Germany in the late 1940s, as they do about me personally and my parents. If I am still haunted by my memories, I am further haunted by the attempts to record the horrific results of bombings—in texts, paintings, and photographs. I have to admit that I hope that this haunting is contagious, and that the reader will thus join me in witnessing images of catastrophe.

2 Joel Agee, Twelve Years: An American Boyhood in East Germany (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 30.

Françoise Meltzer is the Edward Carson Waller Distinguished Service Professor in the Humanities, professor in the Divinity School and the College, and chair of comparative literature at the University of Chicago. She is the author of five books, most recently Seeing Double: Baudelaire’s Modernity, and is a co-editor of the journal Critical Inquiry.

Upcoming book events:

December 12, 2019, Paris: The University of Chicago Center in Paris

March 12, 2020, Chicago: Seminary Co-op Bookstore, with W. J. T. Mitchell

Dark Lens is available now from our website or your local bookseller.