We Are All Fluxus Artists Now: Natilee Harren on Making the Most of Mundane Tasks

As we continue to shelter at home and stay safe during the current pandemic, many of our days are occupied by the routines of cooking, cleaning, eating, and maintaining the household. During this time, Fluxus Forms author Natilee Harren looks to a peculiar group of artists, the Fluxus collective, to cast new light on our mundane daily tasks. Fluxus artists found creative value in a variety of surprising places, including the rituals of seemingly boring everyday tasks. Harren shows us how, even while staying safe at home, we can observe ourselves, become an object, and live some Fluxus art.

Museums and moviehouses continue their closures. Countless events remain canceled. As we practice enforced or voluntary forms of social distancing, we are bombarded with appeals to satisfy our cultural appetites with virtual museum tours, Instagram conversations, live-streamed concerts, and hours of content newly liberated from paywalls. But how much time per day can we really spend with our eyes fixed on digital screens, especially when so many of our work and schooling obligations have also moved online? At the same time, stuck at home and attempting to keep a virus at bay, we find ourselves spending more time than ever before on mundane, everyday tasks like cleaning and cooking. “Wash your hands and face,” I constantly remind my elder son. Instead of ordering out, we use what we have instead and simply “Make a salad.”

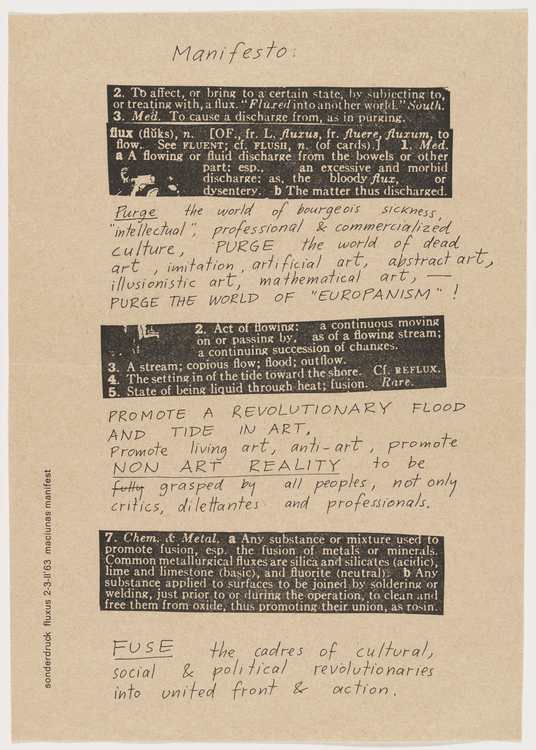

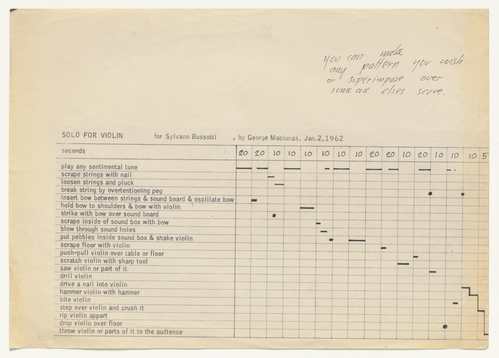

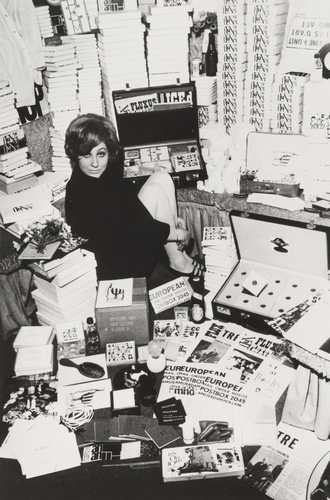

The countless daily reminders we now hear for coping with life under social distancing sound to me unmistakably like the performance instructions or “event scores” written by artists associated with Fluxus, an international avant-garde art movement founded in 1962 with outposts scattered across Europe, Japan, and the US, including a New York headquarters spearheaded by the Lithuanian emigré George Maciunas. Fluxus artists—including Benjamin Patterson, Alison Knowles, Dick Higgins, Robert Watts, Nam June Paik, and (most famously) Yoko Ono—rejected the grandiose expressions of modern painting and sculpture in favor of quotidian gestures reframed as performance art and readymade objects assembled into gamelike kits, which they sold at affordable prices. Fluxus artists sought to highlight commonplace phenomena as intrinsically aesthetically pleasing and even sometimes breathtakingly transcendent. They turned to non-virtuosic modes of creativity while circumventing mainstream museum and gallery contexts in search of sympathetic audiences. Most relevant to us now, their humble practice centered on modest, improvised rituals performed in the face of great uncertainty. They welcomed experimental processes, not always knowing what the outcome of their actions would be.

In fact, “Please wash your face” is an event score composed by Benjamin Patterson. Classically trained as a double-bass player, beginning in the early ‘60s Patterson adopted experimental approaches to music that embraced non-musical sounds and visual theater. Like many Fluxus peers, he was influenced by the genre-busting practices of composer John Cage and the French Dadaist Marcel Duchamp. And “Make a salad” (Proposition No. 2, 1962) stands among the most famous works of Alison Knowles, whose scores often revolve around routine activities of caregiving. (Throughout her career, Knowles has maintained a particular affinity for the newly in-demand vegetable protein, the bean.) In 2008, Knowles’s salad was spectacularly staged at the Tate Modern with tarps and sterilized lawn rakes and more recently revived at the High Line, Walker Art Center, and LA Phil. True to the Fluxus way, however, the salad you might make yourself today is just as good, if not better. Likewise, the next time you wash your hands you might consider the act a realization of George Brecht’s Drip Music (Drip Event) (1959-1962): “A source of dripping water and an empty vessel are arranged so that the water falls into the vessel.” No need for performance anxiety, since it is just as well if you as the performer are also the work’s sole audience. As Brecht once said, “No catastrophes are possible.”

As frames for heightened attention, Fluxus event scores raised contemplative awareness to an art form, anticipating the contemporary resurgence of mindfulness practices. Eminently transportable and do-it-yourself, the format was also a facile tool for connecting like-minded artists internationally, as proven by Japanese Fluxus affiliate Mieko Shiomi’s Spatial Poems. Between 1965 and 1975, Shiomi sent out instructions to her global network, whose responses she collected, documented, and recirculated while continuing to meet her obligations as a stay-at-home caregiver. She reflected, “After one had run around giving concerts and attending other people’s concerts and performances, it was frustrating to be physically restrained to one place at a time. I felt that art should be alive everywhere all the time, and at any time anybody wanted it.” In light of works such as Shiomi’s, French artist Robert Filliou considered Fluxus to be part of an Eternal Network of artists who were conceptually close despite being separated by vast physical distances.

I think often of these historic Fluxus examples as I appreciate the poetic resourcefulness of artists who are now sharing the moments of beauty and joy they have discovered or made in our current dramatically constrained circumstances. David Horvitz is sharing the daily lessons he’s invented for his school-aged daughter as they imagine alternative systems of measurement, consider where our water comes from, and plant scavenged seeds in their tiny Los Angeles garden. Matthias Merkel Hess has been posting the colorful pancakes he has whipped up for his kids: landscapes, abstracts, and geometric designs that quote his practice as a ceramic sculptor. In Houston, the family art collaborative Hillerbrand+Magsamen has assembled junk drawer items into hilarious devices imagined to fix intractable social problems, and Lisa E. Harris tended to an improvised installation of found chairs for the benefit of her immediate neighbors. Pablo Helguera will sing you a telegram, 2Fik is filming tiny dances in drag, and Felicity Allen is sharing images of objects from her home that remind her of friends and loved ones who are also in physical isolation, far away.

Of course, the point of Fluxus is that you can do their pieces too. Wash your face. Make a salad. Play some Drip Music. Or, if need be, perform Dick Higgins’s Danger Music No. 17 (1962)(“Scream!! Scream!! Scream!! Scream!! Scream!! Scream!!”) Once you get the hang of these scores, compose your own daily instructions to perform as the artists I’ve mentioned above have done. Now is the time to discover or reinvent your personal rituals and reframe them as art. In the philosophy of Fluxus, everyone’s an artist and everyone can do it. In any case, this is what I do when I don’t know what to do: Pay attention to artists. They know not just how to survive, but how to live—with creativity, wit, compassion, dignity, and grace.

Natilee Harren is the author of Fluxus Forms: Scores, Multiples, and the Eternal Network, now available from our website or your favorite bookseller. She is assistant professor of modern and contemporary art history at the University of Houston.