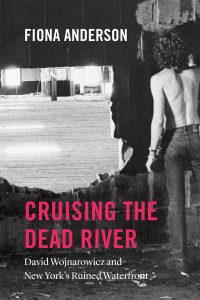

Read an Excerpt from “Cruising the Dead River: David Wojnarowicz and New York’s Ruined Waterfront”

Polymath artist David Wojnarowicz blazed a singular trail through the New York avant-garde from the 1970s until his untimely death in 1992. His incendiary and deeply personal work—often physically and spiritually rooted in the desolation of the Manhattan waterfront—roamed freely between painting, photography, film, and music to confront mainstream inaction on the AIDS epidemic. With the new documentary Wojnarowicz screening now in virtual cinemas, it’s the perfect time to revisit Fiona Anderson’s Cruising the Dead River: David Wojnarowicz and New York’s Ruined Waterfront, which Attitude Magazine called “a fascinating journey in cruising, sex, and the art scene of Manhattan’s dilapidated waterfront in the 1970s and 1980s.”

Detailed descriptions of sex at the West Side piers appear in David Wojnarowicz’s personal journals from the summer of 1977. Walking “through Soho and over to Christopher Street” that September, he found himself in the dilapidated districts he had spent time in as a hustling teenager, by “the big pier past the old truck lines and the Silver Dollar Café/Restaurant.” There, he wrote, “away from the blatant exhibitionist energies of the NYC music scenes gay scenes,” he felt “uncontrollably sane.” In journal entries, poetry, memoir essays, photographs, short films, and drawings, he depicted the derelict piers of the pre–HIV/AIDS era as busy “sexual hunting grounds,” and the ruined waterfront as a liminal space “as far away from civilization as I could walk.” In an interview with the curator Barry Blinderman in 1990, years after many of the dilapidated structures had been torn down, Wojnarowicz recalled the pull of these “extraordinary warehouses where a lot of sexual activity occurred, where a lot of homosexual men would roam the hundreds of rooms of those abandoned shipping structures and engage in open sex.” The gargantuan buildings were, he wrote, like some kind of museum with vast numbers of tourists rolling in off the streets in crowds—gliding through the hallways and rooms, picking their way over trash and fire charred heaps. Upstairs they filled every room, half the ceiling fallen in and they stopped carefully around charred beams and rusted metal and glass—a guy here or there with shorts down around ankles playing with his hard cock or getting fucked by someone else.

In Wojnarowicz’s writing from the late 1970s, as in that of Edmund White, Andrew Holleran, and John Rechy, the decaying form and dangerous character of the warehouses and piers assume an erotic role in the cruising that takes place there. The ruined piers are rendered in fleshy, bodily terms. John Rechy, in the opening chapter of his novel Rushes (1979), wrote of “haunted male figures lurk[ing] for nightsex in the burnt-out rooms, among the rubble of cinder, wood, clawing cans, broken metal pipes, tangled wire like dry veins.” Decay was both mourned and celebrated, in what Holleran characterized as a “nostalgia for the mud.” There were “slight traces” in the warehouses, Wojnarowicz observed, of “déja-vu, filled with old senses of desire,” with erotic remnants of the harbor’s maritime history. In a journal entry from June 1979 he wrote of “the semblance of memory and the associations” invoked as he cruised the West Side piers, reminded “of oceans, of sailors, of distant ports and the discreet sense of self among them, unknown and coasting.”

In The Power of Place, Dolores Hayden argues for a history of place focused on the “traces of time embedded in the urban landscape in every city,” for they “offer opportunities for reconnecting fragments of the American urban story.” The recording of history in the urban context, she asserts, should be a collaborative, multitemporal process that “engages social, historical, and aesthetic imagination to locate where narratives of cultural history” are “em- bedded in the historic urban landscape.”

In a similar way, “restless walks” through Manhattan to the West Side piers left Wojnarowicz “filled with coasting images of sights and sounds . . . like some secret earphone connecting [him] to the creakings of the living city” and the erotic traces “embedded” therein. The waterfront was filled with traces of his own youthful experiences as a street hustler, as well as, in more general terms, its earlier sexual appropriations by sailors and stevedores when New York’s harbor was still an active port. In a later essay, “Losing the Form in Darkness,” he wrote of the industrial paraphernalia that littered the warehouses: “paper from old shipping lines scattered all around like bomb blasts among wrecked piece of furniture; three-legged desks, a naugahyde couch of mint-green turned upside down.” In the same essay, he reflected on “the sense of age” in this “familiar place”:

The streets were familiar more because of the faraway past than the recent past—streets that I walked in those odd times when in the company of deaf mutes and times square pederasts. These streets are seen through the same eyes but each time with periods of time separating it: each time belonging to yet an older boy until the body smooths out and lines are etched until it is a young man recalling the movements of a complicated past.

Wojnarowicz’s nostalgic cruising sensibility, his sense of these “traces” of cruising pasts rooted in the derelict warehouses of the waterfront, of a “secret earphone,” offers a point of entry into an alternate history of Manhattan’s queer fringes and its erotic former uses that, through his conflation of the waterfront’s erotic pasts and present, reflects the complex, multilayered rela- tions between the cruising cultures of the trucks, the bathhouses, the piers, and the men who cruised there.

In Backward Glances, Mark Turner traces a history of urban cruising that begins with the Industrial Revolution and the development of the modern metropolis in the mid- to late nineteenth century. Cruising in both New York and London was and is, he writes, “an act of mutual recognition amid the otherwise alienating effects of the anonymous crowd.” It is, he argues, “a practice that exploits the fluidity and multiplicity of the modern city to its advantage,” a “process of counter movement” that “necessarily resists totalizing ways” of narrating the temporal and spatial character of cruising. Cruising is, Turner emphasizes, “the stuff of fleeting, ephemeral moments not intended to be captured.” Tim Dean offers a similar account in Unlimited Intimacy, his book on contemporary barebacking cultures. “Since cruising is a practice of the ephemeral and the contingent,” Dean argues, echoing Charles Baudelaire’s paradigmatic definition of the experience of modernity, and Turner’s evocation of it in Backward Glances, “it is all the more remarkable that it has given rise to such a voluminous archive.”

Cruising, then, even as it exploits urban anonymity and is structurally dependent on movement and ephemerality, has a queer historical orientation that is both imaginative and material, as is perceptible in the erotic use of ruined buildings along the Manhattan waterfront in the late 1970s.

Fiona Anderson is a senior lecturer in art history in the Fine Art Department at Newcastle University.

Cruising the Dead River: David Wojnarowicz and New York’s Ruined Waterfront is now available from our website or your favorite local bookseller.