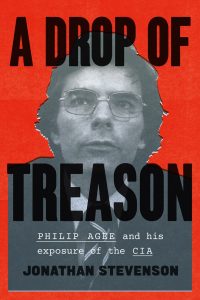

Read an Excerpt from Jonathan Stevenson’s New Spy Biography “A Drop of Treason: Philip Agee and His Exposure of the CIA”

Philip Agee’s story is the stuff of a John le Carré novel—perilous and thrilling adventures around the globe. In 1975, he became the first person to publicly betray the CIA—a pariah whose like was not seen again until Edward Snowden. For almost forty years in exile, he was a thorn in the side of his country.

The first and only biography of Agee, A Drop of Treason is a thorough portrait of this contentious, legendary man and his role in US history during the Cold War and beyond. It was published this May, and we’re pleased to share an exclusive excerpt with our readers, from Chapter 8: ‘Posterity for a Traitor’.

Literary immortalization as an antagonist’s foil is a form of political and moral validation, and Agee has secured at least that much. He stayed part of the espionage conversation for over thirty years after publishing Inside the Company on account of his intimate knowledge of the CIA’s modus operandi and his unflagging insistence on its counterproductive amorality: despite the aspersions that the agency and others cast on his character and integrity, objective observers could never be sure that he was wrong on the merits. Len Weinglass, who represented the Cuban Five, met Agee toward the end of his life and was able to take his measure as an éminence grise of the dissident community. “It must have driven the CIA crazy,” he reflected, “to try to attack the credibility of a man so eminently credible.” The CIA itself declined public comment on his death.

For all his genuineness and his unstinting dedication to his cause, Agee behaved far more objectionably than necessary or proper to make his point. Most Americans would undoubtedly contend that his treason was more than just the “drop” that Rebecca West contemplated to keep good nations true to their foundational principles. While originally writing mainly about British fascists who abetted Nazi Germany, in a later edition of her classic book The Meaning of Treason, she showed little mercy for Cold War–era turncoats. Paradoxically, though, Agee’s point might not have been so catalytic or so durable had he not lodged it in the dramatic and consequential way that he did. And he probably would not have been compelled to perpetuate his lifelong campaign against the CIA had he not burned his bridges to the establishment so irreversibly, leaving himself no honorable option besides staying the course. He was perhaps as close to an embattled antihero as he was to an outright cad.

If Agee seemed like a wasting asset as the Cold War ended, it was only because the Clandestine Service was atrophying and the CIA itself becoming a less active player in the execution of US policy. Once 9/11 effectively reempowered the agency, and it went nefarious again with renditions, black sites, and torture, his mission again became relevant to upholding true American principles. Thanks to some extent to Agee and his followers, disclosures by guilt-ridden or merely conscientious spies were less likely to condemn them to iniquity than to earn them some qualified respectability. Whatever his precise motivations, the strain of Agee’s grievance was one of the twentieth century’s successful viruses: undeniably effective and impossible to kill.

Counterintelligence analysts use the mnemonic “MICE” to identify the basic motives for betrayal: money, ideology, compromise, and ego. As US intelligence agencies have increasingly employed second- and third-generation immigrants, competing nationalism has become another key factor. On the surface, the MICE categories are objective and value-neutral, and such analysts are sophisticated enough to recognize that human behavior is complex and rarely driven by a single motive. But the very premise of the counterintelligence vocation—that someone seeking to damage vital national interests must be stopped—logically crowds out the plausibility of a valid motive, such as political justification. Nevertheless, it remains possible. However complex Agee’s psychology and however questionable his actions might have been, he made a reasonably defensible and uniquely informed argument that American foreign policy was, against the received view of the United States’ honor and nobility, in fact duplicitous and mercenary. As Christopher Moran notes, “Agee, in particular, showed that the engine of foreign policy was fuelled not by any devotion to morality or democratic values, but by a desire to make the world hospitable for globalisation, led by American multinational corporations. Renegades and whistleblowers also revealed the forgotten victims of US strategy abroad, such as the people who suffered under the authoritarian Shah of Iran, installed by the CIA (and MI6) in 1953. In sum, they held a mirror up to the face of the nation; few liked the reflection staring back.”

In a palpable way, Agee’s life and story recast the conventional American sense of those periods. He was perhaps the only CIA officer who turned against the agency for reasons that were truly and deeply political. While Marchetti, Snepp, Stockwell, and others did have cognate experiences with the agency, Agee took his political commitments beyond narrow, circumscribed attacks on analytical misrepresentation and excessive secrecy into a lifelong political struggle with the agency that firmly allied him with the social movements of the global Left from the late sixties until his death. The wholesale condemnation of the American project is the one thing the CIA cannot tolerate. The resulting fury against Agee has lingered in intelligence historiography as well as in the agency itself, leaving him the caricature of a disaffected traitor or, at best, a demonized symbol. Perhaps now he appears a more substantial and full-blooded character than that.

Greg Grandin has pointed out that, although “on one level the Cold War was a struggle over mass utopias—ideological visions of how to organize society and its accoutrements—what gave that struggle its transcendental force was the politicization and internationalization of everyday life and familiar encounters.” Agee was the kind of public figure who, for better or worse, embodied exactly that in airing his grievances in Europe and taking them to Central America as part of the Solidarity Movement. In so doing, he helped demonstrate that, as Nick Witham has observed, “in order to be effective, peace activism needed to be fundamentally transnational in scope.”66 Beyond that lesson, the proposition—posed by the sheer durability and persistence of Agee’s convictions—that an American traitor’s conduct may be politically justified has become more salient since the end of the Cold War, perhaps because the geopolitical stakes have not seemed as high. Even Snepp, who has always taken pains to distinguish himself as a tortured patriot in contrast to Agee’s abject “turncoat,” conceded Agee’s philosophical genuineness, in 1999 characterizing him as a Catholic who had experienced an “inversion of faith” and a “true believer.” Americans have taken a far more nuanced and sympathetic view of Edward Snowden than they did of Agee: in an August 2018 Rasmussen Report poll, while 29% considered Snowden a traitor and 14% regarded him as a hero, a large plurality—48%—saw him as a more complicated and ambivalent figure.

The possibility of a principled and acceptable rejection of the US government seems to loom especially large in the age of Donald Trump. Trump’s grim ascent would have appalled and depressed Agee all over again. Certainly he would have seen the Trump administration as confirmation that the entire US government (not just the CIA) was an agent of and a front for American corporate interests and capitalism, cloaked in toxic populist nativism. And he would have read the Trump administration’s bureaucratic beleaguerment of the CIA as the systematic suppression of its only possible legitimate function: providing objective analyses of collected intelligence. It may be tempting to think that, in light of Trump’s distrust of the CIA, Agee might have found himself rooting for his old agency and nemesis as the lesser of two evils. More likely, though, he would have considered his own comprehensive rejection of US policy and national security institutions as pyrrhically vindicated by Trump’s transmogrification of American government and governance. So emboldened, he might have pointed out that the integrity and loyalty of an intelligence service ultimately depends on its officers’ pride in and respect for the country they serve.

That pride and respect can survive, and have survived, episodic and even epochal lapses. In this respect, Agee was unusually thin-skinned. At the same time, his life itself exemplified the brittleness of the American vision. His detractors might say he just got mildly disenchanted with CIA work; tried to take the quiet, nontreasonous way out; got frustrated; was seduced by a couple of lefty women; felt the allure of dissident celebrity; and only then became a real dissenter. On the known facts, that’s a gross oversimplification: Agee paid for his proclaimed beliefs with lifelong anxiety and displacement. But even if the more dismissive account of Agee’s turn were accurate, the accidents and coincidences that produced Agee’s turn wouldn’t make it any less genuine or durable.

No president before Trump has assaulted the country’s constitutional and ethical pillars so savagely or frontally. As he refused to recognize his loss to Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election and sought to subvert American democracy altogether, ultimately inciting violence, a wholesale loss of faith in the American project seemed a salient possibility. The extraordinary jeopardy that Trump poses to the United States’ constitutional democracy reinforces what would surely have been Agee’s view: that disloyalty, in the first instance, is not a matter of moral or psychological weakness but rather is acutely contingent on particular circumstances. If they are dire enough to stay planted in moral memory, disloyalty becomes a habit of mind—that’s the giddy line—and then a compulsion to act. Especially in ethically testing conditions, the boundary between loyalty and betrayal is inherently unstable to those who are truthful to themselves. What Pico Iyer said of Graham Greene applies equally to Agee: “Always there was a dance in him between evasion and an almost ruthless candor.” So he got used to walking that giddy line, and stayed, if barely, on his feet. This was not an entirely masochistic dispensation, of course. Iyer also said that Greene, and by extension Agee, “seemed to feast on confrontation, perverse of paradoxical positions, as if he would take any stance so long as it kept him apart from the crowd.”

His turn, ever public, afforded Agee the psychological satisfaction of being unique. Perhaps several dozen disgruntled intelligence officers have followed his lead, but few if any of them have equaled his level of commitment or so obstructed the system they had once sustained. How many more, girded by Agee’s survival and circulation as a turncoat and disillusioned by a fallen America, might now emulate him?

Jonathan Stevenson is senior fellow for US defense and managing editor of Survival at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. He was previously professor of strategic studies at the US Naval War College, and he has served as director for political-military affairs, Middle East and North Africa, on the National Security Council.

A Drop of Treason is available now from our website or your favorite bookseller.