New Work from the Phoenix Poets

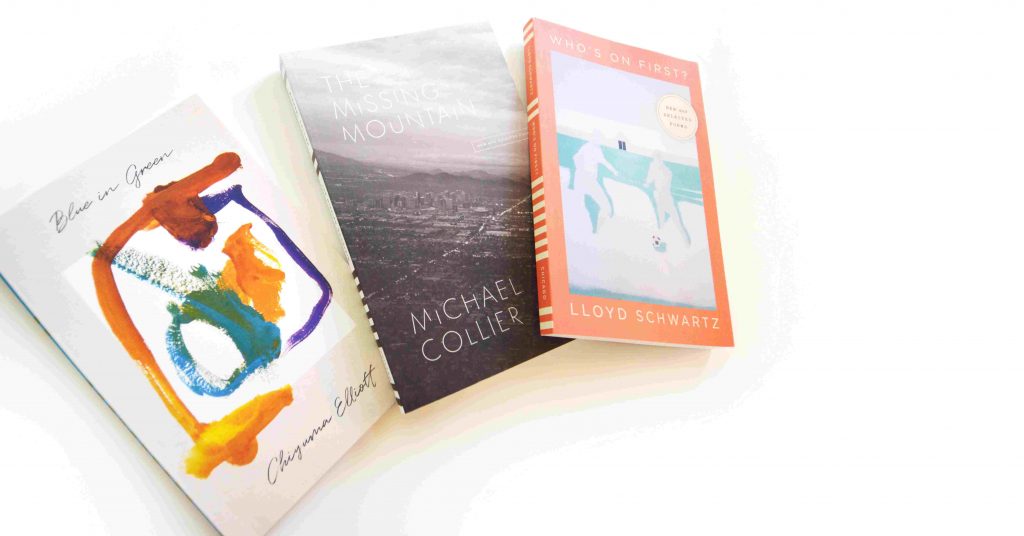

This fall, we’re delighted to be publishing three new titles in our Phoenix Poets series: The Missing Mountain by Michael Collier, Blue in Green by Chiyuma Elliott, and Who’s on First? by Lloyd Schwartz. Below, these three poets tell us a little about their new collections and highlight a poem to give us a taste of their work.

Michael Collier on The Missing Mountain

The Missing Mountain: New and Selected Poems is important to me because it provides a survey of poems I’ve published in books since 1986 as well as a big handful of more recent poems. The collection is organized in reverse chronological order because I want a reader to move backward in time through my development as a poet rather than forward, and then to finish, so to speak, with new poems.

“Len Bias, a Bouquet of Flowers, and Ms. Brooks” records a meeting I witnessed at the University of Maryland in April 1986 between Gwendolyn Brooks, who was giving a reading, and four-time All American basketball player Len Bias, who presented Brooks with a bouquet of flowers. A few months later, Bias died tragically of a drug overdose, a few days after he had been drafted by the Boston Celtics.

“Len Bias, a Bouquet of Flowers, and Ms. Brooks”

He arrives in the middle of her reading. She

has to stop and, taking the flowers he’s brought, kisses

the beautiful young man whose yellow socks are her

dowdy sweater’s antithesis. What’s said between them is killed

by applause, but not his smile, which is the smile of a boy

standing in the silence he’s created, and

not her magnified stare, which says she

understands why he’s arrived late, is

already leaving, and that he is sorry.

What sparked the poem was an invitation, in 2016, to contribute a Golden Shovel to The Golden Shovel Anthology: New Poems Honoring Gwendolyn Brooks. (A Golden Shovel is a poetic form invented by Terrance Hayes in which he used lines from Brooks’s “We Real Cool” to provide the end words to formulate his own poem.) As I began thinking about how I might write a poem honoring Brooks, the thirty-year-old memory of her encounter with Len Bias came back to me, and then, as these things happen, I was led to the lines that would be the basis of my Golden Shovel. Usually, I take an excruciatingly long time to write a poem but this one came quickly as if I’d been waiting years to get it down.

My favorite lines, of course, are the ones I happened upon for my Golden Shovel. They come from Brooks’s “The Last Quatrain from the Ballad of Emmett Till” (‘She kisses her killed boy. / And she is sorry.’) The lines with their ‘kiss,’ ‘death,’ and ‘sorrow’ seemed to uncannily and heartbreakingly link Bias’s fate to that of Emmett Till’s.

Chiyuma Elliott on Blue in Green

There’s always a governing question for the books I write. When I find the question, that’s when the book starts to cohere. Blue in Green is about collaboration, and its governing question is, “What do we owe one another?” When I wrote the book, I was staring down the barrel of an early cervical cancer diagnosis—and even though there’s such good treatment for it, I was really scared. Probably because I took care of my mom-in-law, Ginny, during her terminal lung cancer fight, so the bodily realities of a “collaboration” with metastasis felt utterly vivid to me. I pushed hard to finish the book because I knew I wanted to dedicate it to my friend Katie, my wing-woman in all important things. I was reading my colleague Tina Sacks’s research on racial bias in medicine and thinking about loyalty and betrayal (both societal and interpersonal) and feeling this weird mix of fear and anger and wonder and gratitude. So that’s what went into the poems.

I think the title poem captures a bunch of things I tried to pull together: the connections between music and poetry, the intimacy and mystery of close human relationships, and the natural and social and political backdrops against which art and companionship happen. It was also the hardest poem to finish! My big goal was to describe the famous jazz song. So I put Miles Davis on repeat while I wrote (which really annoyed my dogs). Then I’d put the poem away for a couple of weeks and try again. The euphorbia in the poem are real; they grow along the Montclair Railroad Trail by my old house in Oakland. I like the toggle between uncertainty and certainty in the poem: “maybe” “of course” “what happened?” Euphorbia seem utterly certain to me, and their weird acid green felt clarifying when I was trying to make this poem come together.

“Blue in Green”

Stop working against the world, I counseled myself. Love the one you’re with.

Love the color green.

—Maggie Nelson, Bluets

I imagined mornings: two plates, a worn table.

Nights a composite of the same small things.

I chronicled the history of segregated boardwalks.

I stirred my coffee with improbable plastic straws.

I imagined falling on a slick surface. No,

you held fast. Or maybe you stood on tiptoe

and blew smoke out the high bedroom window.

Maybe we were arguing about paintings.

Maybe I just imagined the digressions. Your letter read

Dear Day in Mid-to-Late October,

of course I concluded there was never any ballast.

The clocks fell back.

The euphorbia argued their case in simple terms.

What happened? I watched the sky; I stood on tiptoe.

I downplayed the mystery; I carried it

in a compartment of my purse.

Lloyd Schwartz on Who’s on First?

I hope my title Who’s on First? suggests some of the central qualities of my poems. I like poems with a sense of humor or at least a sense of irony. And I prefer poems that ask questions rather than give answers. James Merrill once called the poems in my first book “Chapliniana.” That was exactly what I hoped—that my poems might be both comic and touching, like Charlie Chaplin, and very much in the vernacular. I know I could never write like the great poets of the past (and I suspect no one alive today should), but I also believe that plain-spoken language can also have real eloquence. I think I became my own poet once I stopped trying to write like the poets who first made me love poetry.

This collection includes not only new poems but also a selection of my earlier poems. The very earliest poems are the ones in which I first turned toward something less “poetic” and more “dramatic”: i.e., monologues and dialogues, in which characters reveal themselves through what they say and how they speak. My poem “Six Words” is a kind of quintessential dialogue—the most pared-down version of the kind of poem I’d begun writing in my first book.

“Six Words”

yes

no

maybe

sometimes

always

never

Never?

Yes.

Always?

No.

Sometimes?

Maybe—

maybe

never

sometimes.

Yes—

no

always:

always

maybe.

No—

never

yes.

Sometimes,

sometimes

(always)

yes.

Maybe

never . . .

No,

no—

sometimes.

Never.

Always?

Maybe.

Yes—

yes no

maybe sometimes

always never.

A fundamental quality of poetry is repetition. In my poetry workshops, I want my students to learn the fundamentals by experimenting with some complicated traditional forms. Like the sestina, which forces you to keep its required repetitions interesting and surprising. One student asked me if I had ever written a sestina, and I had to admit that I had never been able to finish one. I was embarrassed enough to try again. And since the first great sestina in English—by Sir Phillip Sidney—was a dialogue (right up my alley), I thought maybe my own sestina could be a dialogue too. And since sestinas are long (39 lines), and too many of them seem too long, I wanted to write the shortest one possible, with only one word per line. I knew fairly quickly what my six repeating words would be—pairs of simple contradictions, in some ways a condensed version of the couple arguing in my title poem. “Six Words” took me about ten minutes to “compose,” but months to punctuate, because the real challenge here was to make these six ordinary words not only meaningful but also full of innuendo. It’s one of my favorite poems to read aloud, and I’m especially happy that a composer I especially admire chose to set it to music. A duet, of course.

All three books are available from our website or your favorite bookseller.