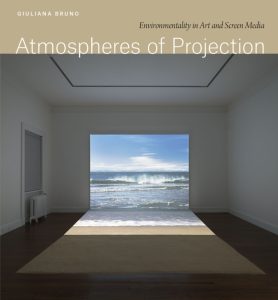

Read an Excerpt from “Atmospheres of Projection” by Guiliana Bruno

In her new book, Atmospheres of Projection: Environmentality in Art and Screen Media, Giuliana Bruno brings together cultural history, visual studies, and media archaeology to consider the interrelations of projection, atmosphere, and environment. Looking deep into our fascination with projection and atmosphere, Bruno traverses psychoanalysis, environmental philosophy, architecture, the history of science, visual art, and moving image culture to see how projective mechanisms and their environments have developed over time. In this excerpt, she offers a look at the production of “atmospheric thinking” and traces how some of our ideas about atmosphere and ambiance came into being.

IN LIGHT OF THE INVENTION OF ATMOSPHERE

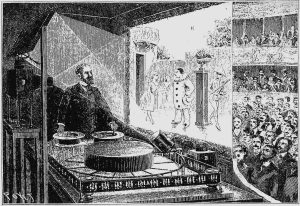

“The whole marvelous panorama of life that spreads over the surface of our globe is, in the last analysis, transformed sunlight.”—Ernst Haeckel

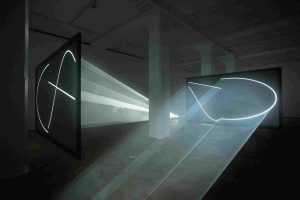

This modern, fluctuating, transformative wave of atmospheric imagination, which was produced in experimental projective geometries and in the scientific exploration of light, developed concurrently with the imaginative ambiance and fluid space of the art of projection. The luminiferous atmosphere of cine-projection is equally modern born as it was out of the rays of modernity—that is, in its very light. And in light of this “atmospheric thinking,” we should note another historical conjunction that emerged around the notion of ambiance, which further supports a more expansive, environmental, energetic view of the “projective imagination.” Cine-projection developed at the same time that the term ambiance was established as a noun, appearing in French dictionaries in 1896. This factor is relevant in our archaeological mapping of the energy of the cultural context that surrounded the emergence of projection.

Let us follow, then, the semantics of ambiance and the course of its subtle passages and contaminations. Before the noun, the adjective ambient was used in mostly scientific contexts to mean “what goes around“ in space, having developed from the Latin verb ambire, which defined ambulatory activities as well as the kind of encircling that we have said is proper to an atmospheric embrace. The modern term ambiance was used predominantly in relation to artistic matters but also in philosophical, sociopolitical, and anthropological discourse, in part as a synonym for the more positivist notion of milieu. But it also came to carry different, multiple inferences and associations, referring, as one art critic recaps, “to light, brightness, air, limpidity, mixed with the dynamic sense of a fluid matter enveloping and embracing people and things.” Milieu maintained more empirical connotations; it developed, as the philosopher of science Georges Canguilhem explains, from the mechanics of physics, moved to biology as a behavioral notion, and ended up encompassing sociological implications in defining an anthropological and geographic setting or surrounding. Ambiance would expand the meaning of milieu, understood as a mid-place, medium, or in-between, as well as its connotation of environment, or Umwelt, as developed by Jakob von Uexkull. This biophilosopher resisted the more deterministic aspect of milieu and, as film theorist Inga Pollmann suggests in a study of vitalism, was also interested in the technical medium of chronophotography, which captured motion through multiple images. His Umwelt defines the character of the world surrounding organisms as being subjective as well as objective, with correspondences between the two. Uexkull even sought to expose the more subjective environment that encompasses every living form and being.

This expanded notion of surroundings builds on the idea of the existence of an ambient element first formulated by the ancient Greeks and subsequently reprised by modern science to define “what goes around.” Such motility refers in particular to the (im)material consistencies of fluids or air, that is, to the space surrounding and encircling living bodies and the bodies of things. Ambiance, then, further develops that notion of “ambient medium” discussed by Spitzer, via Newton, as a field of forces, connoting the fluid movement of the sensible world. And so it goes that, by the end of the nineteenth century, the connotations of ambiance shift from the biosociological sphere to a realm closer to that of atmosphere, with its affecting elements, or to “climate,” arriving finally to be understood as “an air,” even in the spiritual sense. In other words, with modernity, the era in which the technical reproducibility of media creates atmospheres of projection, ambiance itself becomes more atmospheric. It takes on the character of a more elemental, ecological, evanescent, and affective “technical medium.”

The term atmosphere, as understood in the scientific realm, likewise emerged at a particular historical moment. Combining the ancient Greek words for vapor and sphere, the idea of atmosphere made its appearance in early modernity, at the beginning of the seventeenth century. A concept of natural philosophy, it spread rapidly from astronomy and mathematics to multiple areas of research, ranging from meteorology to cosmology, medicine to botany. Discussions arose in various fields about the aerial region—the pneuma or vapor—surrounding the earth, and especially about the composition of the substances that permeate the earth’s surface and extend all the way to the stars, often described as blankets of air, effluvia, exhalations, or emanations. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, even climates were widely spoken of as circumfusa, that which sheathes and flows around organisms. The idea was to grasp an ethereal form of circumnavigation that, as Eva Horn puts it, “engulfs and transports the bodies of living beings, be they plants, animals, or human beings, in an ever-moving, ever-changing medium.”

As for the sciences proper, these discussions also involved light, as historian Craig Martin shows in his study of “the invention of atmosphere,” especially the quality of twilight and the refraction of sunlight. Because luminous refraction requires light to pass through a substance, atmosphere was engaged, analyzed, and mathematically measured. Interestingly, it did not emerge as ethereal, nor as pure air, diaphanous or transparent. It was rather assigned degrees of limpidity and deemed opaque, turbid, or even gloomy, in more affective terms. And, with this material consistency, in the middle of the seventeenth century, the concept of atmosphere changed in scientific circles, in even more fluid ways, with the advent of the pneumatic experiments of Pierre Gassendi, Walter Charleton, and Robert Boyle. The atmosphere of the mathematicians was transformed, with added characteristics not only of weight and gravity but also of pliability and fluidity. The nature of vacuity and the possibility of assigning weight to air or its particles created disputes about the borders and extent of the atmosphere, and its capability for expansion, seen as curling in waves. Its density or rarity, qualities implicated in its capacity to refract light, suggested a morphing matter of condensed air or gases.

In other words, with modernity, the era in which the technical reproducibility of media creates atmospheres of projection, ambiance itself becomes more atmospheric.

By the rise of modernity, then, the earth was seen to possess an encompassing, layered atmosphere, which surrounded and moved around everything, including flora and fauna, other planets, and everything solid. The concept resulted in the idea of an elastic blanket, a pliant, “fluid substance made of corpuscles and effluvia.” Thus comprised of fluid bodies and layers that are not fixed but rather unstable, atmosphere became defined by flux and movement. In such a way, it became more closely connected to ambiance—the space in which we breathe and move.

Giuliana Bruno is the Emmet Blakeney Gleason Professor of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University. She is the author of several books, including Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture and Film, winner of the Kraszna-Krausz prize for best Moving Image Book; Streetwalking on a Ruined Map, winner of the Society for Cinema and Media Studies book award; Public Intimacy: Architecture and the Visual Arts; and Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality, and Media.

Atmospheres of Projection is available now from our website or your favorite bookseller.