Read an Excerpt from “Deep Water” by Riley Black

What lies beneath the surface of the ocean has mystified humankind for millennia. Today, we have explored more of the surface of the Moon than we have the deep sea. What thrives in these mysterious depths, how did these life-forms evolve from ancient life, and how has this environment changed over time as our planet has developed?

Introducing us to the ancient, complex, and fascinating life forms that have evolved into the marine life we recognize today—from stromatolites, structures created by some of the earliest life billions of years ago and still found today, to yeti crabs, bioluminescent firefly squid, and giant jellyfish—Deep Water is an eye-opening journey into the world far beneath the waves. Our guide, brilliant science communicator and self-described “fossil fanatic” Riley Black, has studied marine biology and paleontology, and she brings her vast knowledge and inimitable voice to our voyage. Through text and image, Black leads us further and further into the depths to reveal how this unique and largely unexplored habitat came into being, what lives there and why, how it has evolved, and what the future will bring in this dark and mysterious environment.

Although Halloween has come and gone, our fascination with some spooky things is without season—among them, vampires and the wonderfully weird organisms of the abyss. Just one of the many creatures Black chronicles in Deep Water, the vampire squid hits all the marks. But does it deserve its fearsome moniker? And is it even a squid? Read on for an excerpt from Deep Water to find out.

In the entire history of zoology, there may not be a more evocative name than Vampyroteuthis infernalis, the “vampire squid from hell”. Even better, the title is an irony. Only a threat to small plankton, the vampire squid looks far more menacing than it truly is.

The discovery of the vampire squid came during a time when oceanography was only just beginning to come into its own as a science. In the mid-nineteenth century, some ocean experts thought that there wasn’t much life at all below 550 metres (1,804 feet). Trawls from greater depths turned up little, and so much of the ocean deep was thought to be azoic, or without life. The findings of the Challenger expedition in the 1870s changed that picture, documenting many new deep-sea organisms and inspiring naturalists such as German researcher Carl Chun to go searching for even more clues about what lived far below the waves. In 1898–99, Chun was aboard the SS Valdivia, leading an expedition of the same name off Africa, when an odd cephalopod was brought to the surface.

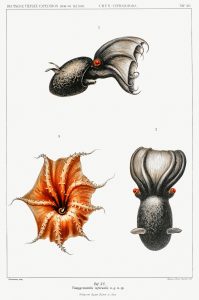

Upon closer study, the cephalopod was extremely difficult to classify. It didn’t seem to resemble any known species. In overall form, Vampyroteuthis looked like an octopus—more bulbous and less streamlined than the squid of the shallows. The cephalopod had eight arms with flexible, thorn-like projections down the middle, yet lacked the specialized feeding tentacles that would be expected of a squid. But the vampire squid doesn’t feed with its arms. Instead, in place of tentacles, Vampyroteuthis has two retractile threads covered in small filaments which help the animal detect and gather small prey and detritus that falls from above. Even though this unique creature is now recognized as being closer to octopus than to squid, it deviates so strongly from octopus anatomy that it is categorized within its own family—the Vampyroteuthidae.

As far as marine biologists know, there is only one living species of vampire squid. Once experts knew what to look for, however, they began to recognize vampire squid in the fossil record. While there is some debate, made all the more difficult by how rare well-preserved fossils of soft-bodied animals are, it seems that vampire squid have been around for at least 120 million years. One fossil, more than 23 million years old, hints that vampire squid have been in deep, oxygen-depleted environments for at least that long. The cephalopods may have become adapted to low-oxygen environments documented in the deep past, and hung on in such harsh habitats ever since.

Today, vampire squid live in the ocean dark more than 600 metres (1,968 feet) below the surface. Even more specifically, and perhaps strangely, the cephalopods prefer a part of the ocean known as an oxygen minimum zone. These oxygen-depleted layers of the ocean usually occur between 200 and 1,000 metres (656–3,280 feet), and most organisms can’t survive here. But vampire squid can. Within this zone, remote-operated vehicles have been able to document how the vampire squid feed—floating along, their feeding filaments extended to hopefully capture whatever pieces of carrion or detritus they might touch. When the squid makes contact with food, it quickly moves towards it and then starts the process all over again. The vampire squid definitely lives life in the slow lane.

Of course, there are other creatures in the deep—and some of them are predators of the vampire squid. Vampyroteuthis does not move very fast, and even its swifter movements quickly drain the animal’s stamina, so the cephalopod has two self-defence tactics. One is to use the bright photophores along the tips of its arms and at the base of each fin, setting off a disorienting light show that makes it harder to locate and catch the squid in the dark world of the deep sea. The other, which marine biologists call the pineapple posture, is to draw its arms up its body to present the predator with its exposed arms covered in spines. Those spines are soft and useless as actual defences, but they might help the squid look like too much trouble to eat.

How do vampire squid manage to procreate in such a distant habitat? What scientists expect mostly comes from other cephalopods, and might change as experts learn more. It’s probably rare for vampire squid to encounter each other so when they do and choose to mate, a male passes a cylinder of sperm called a spermatophore to the female, which she stores in a special pouch until she’s ready to fertilize her eggs and brood. When the squid hatch, they are as small as the plankton that the adults often feed on. To avoid becoming meals, the little ones go deeper to feed and grow until they can return to the waters they came from.

Riley Black is the author of numerous books, including Skeleton Keys, My Beloved Brontosaurus, and, most recently, The Last Days of the Dinosaurs. She has also written about prehistory for publications from National Geographic to Nature and is the resident paleontologist for the Jurassic World franchise. She lives in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Deep Water is available now from our website or your favorite bookseller.