Meet Catherine Theis, Translator of Italian poet Jolanda Insana’s “Slashing Sounds”

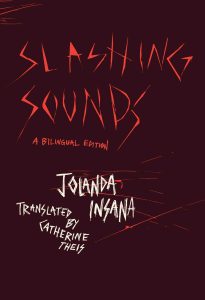

We’re excited to be publishing the first two translated collections of the relaunched Phoenix Poets series this fall! To celebrate new books in the series, we’re introducing Phoenix editors, poets, and translators through a series of short interviews. Here, we spoke with poet and translator Catherine Theis, whose new translation of Italian poet Jolanda Insana’s Slashing Sounds brings the powerful and transgressive poetry of Insana to an English-language readership for the first time.

Tell us a little about yourself and your relationship to poetry.

Poetry is very important to my life, as are ritual and song. And what is poetry if not ritual and song? I remember singing songs with my sister in my great-grandfather’s lemon orchard in a little town right outside of Catania. We’d make the annual trip to clean the graves of our ancestors in the cemetery nearby, and then afterward we’d have a picnic in the lemon groves. We’d dance around with palm fronds or lemon branches and sing in our own made-up sisterly language. As a child, I always sang songs, wrote plays and poems, and read heaps of books. Language operates like a fantastic spell for me. I think it can do anything, if I just put it in the right order and music, as I did in my book of poems, The Fraud of Good Sleep. I don’t believe that you have to be a poet to translate poetry, but I think it helps a great deal when dealing with the elliptical jumps, short circuits, flames, and other transformative moments a poem can bring.

What I try to get across to my students is that poetry requires a spirit of adventure and an appreciation of mystery, even before any meaning is constructed. When my husband and I first were getting to know one another, we’d have these marathon poetry readings at my house. We’d sit around with a lot of wine and just read our favorite poems aloud to one another until the early morning. While we don’t have the time for those kinds of readings, we still share and think about poems with one another. Three years ago, he brought home a copy of Hope Mirrlees’s Paris: A Poem, which I had never read before. Now I’m writing an essay about it. Just yesterday I helped my son’s kindergarten class write a collaborative poem about a garden. I think 90% of my body is made up of poetry.

What made you excited to work with translating this poet’s work?

I just couldn’t believe how audacious Jolanda Insana’s poetry was! I knew I wanted to translate someone with a Sicilian background, but I had no idea someone like her existed. A teacher of mine showed me her poems and the rest is history, as they say. Because I grew up speaking Italian, I felt like it was my duty or service to the arts to translate an Italian poet. My only other desire was that I wanted to translate a woman. I think I’m also contentious and tenacious in my poems like Insana, so I resonated with her language. Her poems are difficult; they require a lot of background, thinking, and feeling. Again, I value poetry that is difficult. I don’t want to be coddled and charmed. I want to work for my art, and I want to be surprised.

How would you describe the significance or role of literary translation today?

Keep the fire going! We need to read more books in translation, buy books in translation, teach books in translation. And, if it’s possible for a person to translate, even a few poems, they should totally do it. In short, we need more people translating. Not only do you learn incredible things about language, but you deepen another part of your consciousness, your being. Translation is just such a wondrous thing—you can do it collaboratively, it’s portable, you don’t need a lot of expensive equipment, it sharpens your critical thinking, it inspires new original work. My father translates Ancient Greek with a group he’s been a part of for close to ten years. Does he publish his translations? No, but he is engaged in a very important tradition of keeping literature alive. Translating keeps the mind and spirit young, I think, but it’s also a way to honor all the writers who’ve come before us.

Tell us a little about your process for translating poetry—are there aspects of the original rhythm or voice you focus on preserving, is there a particular routine or practice you work with, or are there any rules you set for yourself?

Initially, my goal was to just translate the opening poem. I wasn’t really interested in translating the entire collection. But one poem, I could do one poem. Lucky for me, Insana’s “Niente dissi” is a poem with multiple poems. It definitely wasn’t going to bore me. Not only that, but there’s Latin mixed with Italian, oddities, holes, almost no punctuation, sudden drops of a cliff. I liked those features about her work. I wanted to stay very close to her language because so much of her poetry depends upon certain words playing with words at a phoneme level. The music in Insana’s work is also something I needed to be mindful of, I wanted to keep as much “noise” in my translation as possible.

I started very slowly. I did a little bit each day. This was January 2020. Then the pandemic happened, and the world shut down. We moved out of Los Angeles to Tucson, where I got my own loft office at my mother-in-law’s house and filled those two hours after lunch when the baby was sleeping with word weighing. Some afternoons, I just held a phrase like a heavy rock, moving it from one palm to another. Translation kept me somewhat sane during that period in my life. There were lots of unknowns, but I knew if just sat down and worked I’d find contentment, sometimes pleasure.

Most of the time, I felt like I was spinning in place, like my back tires were just stuck in the mud the whole time. Then, occasionally, I found sudden traction and the car would lurch forward on the beautiful open road. I lived for those moments! This project also had me calling my mother whenever I needed to ask her about phrase or word in Sicilian. She has this beautiful pocket-sized Sicilian-to-Italian dictionary I couldn’t get in the desert even if I tried. It’s probably about fifty years old now. I consulted my father a few times, too, since he knows Latin, a little Italian, and Ancient Greek. We always joke about how my father talks like John Wayne in Italian. Translation is very much a collaborative affair in my family.

Anything else you’d like us to know?

I’m thrilled to be a part of the Phoenix Poets Series, especially alongside books like Nicolás Guillén’s The Great Zoo, translated by Aaron Coleman, and Jonathan Thirkield’s Infinity Pool.

More than anything, I’m excited for Jolanda Insana to have a readership in English.

Catherine Theis is the author of the poetry collection The Fraud of Good Sleep and the play MEDEA, an adaptation of the Euripides story. She teaches at the University of Southern California.

Slashing Sounds is now available for pre-order from our website or from your favorite bookseller.