Working for Peace in Israel and Palestine

The NYT published a story today about a new sign of hope for the peaceful co-habitation of the West Bank coming from a group of ultra-Orthodox Haredi Jews living in the outlying communities of Modiin Illit and Beitar Illit. According to the Times, though the rapidly growing populations of their settlements along disputed territories account for much of the Israeli government’s claims for the need to expand into Palestinian territory, “these ultra-Orthodox inhabitants often express contempt for the settler movement, with its vows never to move.”

The people here, who shun most aspects of modernity, came for three reasons: they needed affordable housing no longer available in and around Jerusalem or Tel Aviv; they were rejected by other Israeli cities as too cult-like; and officials wanted their presence to broaden Israel’s narrow border.… Yet they are lumped with everyone else.

With an unsurpassed ideological commitment to their religion, but not to the hardline Zionist movements with which ultra-Orthodox communities are sometimes associated, their desire to divorce themselves from the broader nationalist movement brings new hope for a deal with the Palestinians over many existing land disputes and the possibility of a future in which both groups can co-exist peacefully.

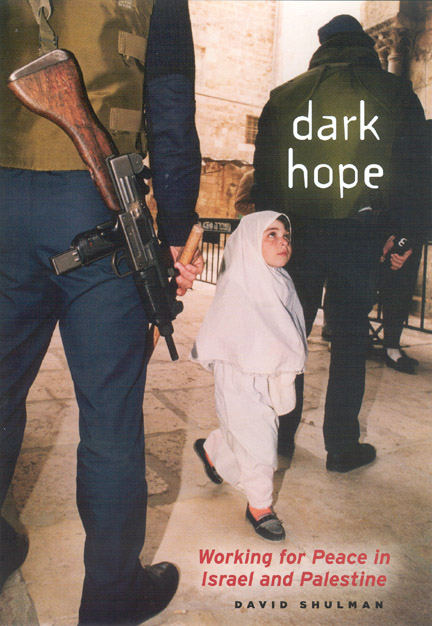

In the summer of 2007 the press also published a book documenting a similar ray of hope for a resolution to the decades long conflict between Israel and Palestine in Dark Hope: Working for Peace in Israel and Palestine—an eye-opening chronicle of the author David Shulman’s work as a member of the peace group Ta’ayush, which takes its name from the Arabic for “living together.” Comprised of both Israeli and Palestinian activists working side by side, Shulman’s book documents the group’s dogged efforts to pass through Israeli checkpoints to deliver aid, rebuild houses, and physically block the progress of the dividing wall. As they face off against police, soldiers, and hostile Israeli settlers, anger mixes with compassion, moments of kinship alternate with confrontation, and, throughout, Shulman wrestles with his duty to fight the cruelty enabled by “that dependable and devastating human failure to feel.”

Offering humanizing accounts of the reality of a people struggling to overcome one of the most complicated conflicts of our era, both the Times article and Shulman’s book make for essential reading on the topic.

For more read the complete NYT article or read an excerpt from Shulman’s book.