Joanna Kempner on Oliver Sacks and migraines

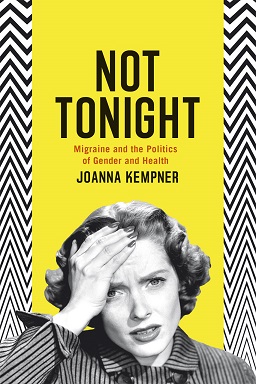

Joanna Kempner’s Not Tonight: Migraine and the Politics of Gender and Health confronts our tendency to dismiss the migraine as an ailment de la femme, subject to the gendered constraints surrounding how we talk about—as well as legislate and alleviate—pain. In the book, Kempner traces the symptoms of headache-like disorders, which often deliver no set of objective symptoms but instead a mix of visual and somatic sensitivities, to the nineteenth-century origins of the migraine, its reputation in the 1940s for soliciting the “migraine personality” (code for so-called uptight neurotic women), forward to present-day sufferers. A couple of weeks ago, following the death of neurologist and writer Oliver Sacks, Kempner published a piece at the Migraine blog on Sacks’s lesser-known first book: called Migraine, it drew upon Sacks’s experience working at Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, the nation’s first headache clinic, and reflected on the neuropsychological effects of migraines.

From Kempner’s post:

The book itself was a tour de force. The backbone of the text is a thorough and eloquent overview of the various forms of migraine (as they were understood in 1970), peppered throughout with case studies from Sacks’ clinical practice. But what made Migraine different from other texts on the subject were Sacks’ unique observations about the disorder, within which he saw “an entire encyclopedia of neurology.” Foreshadowing his future interests in hallucinations and the nature of consciousness, Sacks devoted a large portion of the text to migraine auras, describing in detail both the variety of visual and sensory disturbances that may be experienced and the affective changes that can accompany aura: déjà vu, existential dread, anxiety, or delirium. That he illustrated these discussions with what might have been the first collection of “migraine art” made the book particularly unusual and innovative. Paintings drawn by people who had experienced migraine aura enabled Sacks to visually describe what aura felt like.

Migraine, however, is a book that ought to be read and understood as a product of its time. In 1970, when it was published, psychosomatic medicine ruled headache medicine. It was a time when some headache specialists thought it was perfectly acceptable to attribute migraine solely to rage or personality flaws of the patient. Sacks, importantly, took the position that migraine was always physiological in nature and he steadfastly rejected the “migraine personality”—an idea popular at the time that held that people with migraine were obsessive, Type-A characters. However, Sacks had not given up the psychological completely. He argued that migraine served important psychological functions, for example providing respite for patients. He also warned that, although the migraine personality may be myth, people with migraine had many other problematic personality types that had to be dealt with at the clinic. So, although Sacks was a progressive physician in many ways, reading Migraine now can sometimes be a jarring experience.

One thing is for sure. Sacks’ trademark empathy and compassion for patients shines throughout his work on migraine.

To read more about Not Tonight, click here.

To read an excerpt from the book, click here.