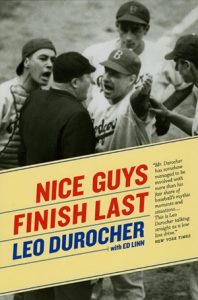

“I come to kill you”: An excerpt from Leo Durocher’s classic memoir of his years in baseball, Nice Guys Finish Last

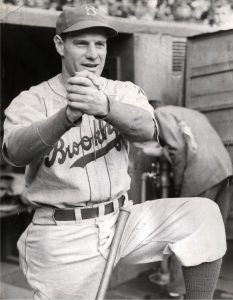

Leo Durocher (1905–1991) was one of the most colorful characters in baseball’s storied history. A playing career that ran from 1925 to 1945 saw him in the uniforms of the Yankees, Reds, Cardinals and Dodgers; he won world championships with New York and St. Louis. In the last years of his playing career, he also took up the managerial reins, winning a pennant with the Dodgers in 1941. After hanging up his spikes, he continued managing until 1973, taking the Giants to the World Series in 1951 and winning it with them in 1954. In Chicago, he’s best known for managing the 1969 Cubs, who blew a giant lead down the stretch and lost the pennant to the Miracle Mets. Through all of this, Durocher’s wit, antics, and irascible personality made him a household name—and a regular guest on radio talk shows in the medium’s heyday. In 1975, Durocher hooked up with veteran writer Ed Linn to write a memoir, “Nice Guys Finish Last.” It quickly became a baseball classic, and the University of Chicago Press was proud to issue a new edition in 2009.

Leo Durocher (1905–1991) was one of the most colorful characters in baseball’s storied history. A playing career that ran from 1925 to 1945 saw him in the uniforms of the Yankees, Reds, Cardinals and Dodgers; he won world championships with New York and St. Louis. In the last years of his playing career, he also took up the managerial reins, winning a pennant with the Dodgers in 1941. After hanging up his spikes, he continued managing until 1973, taking the Giants to the World Series in 1951 and winning it with them in 1954. In Chicago, he’s best known for managing the 1969 Cubs, who blew a giant lead down the stretch and lost the pennant to the Miracle Mets. Through all of this, Durocher’s wit, antics, and irascible personality made him a household name—and a regular guest on radio talk shows in the medium’s heyday. In 1975, Durocher hooked up with veteran writer Ed Linn to write a memoir, “Nice Guys Finish Last.” It quickly became a baseball classic, and the University of Chicago Press was proud to issue a new edition in 2009.

In this excerpt from “Nice Guys Finish Last,” Durocher explains the book’s title (perhaps his most lasting contribution to our culture) and lays out some principles for playing the game Durocher-style.

My baseball career spanned almost five decades—from 1925 to 1973, count them—and in all that time I never had a boss call me upstairs so that he could congratulate me for losing like a gentleman. “How you play the game” is for college boys. When you’re playing for money, winning is the only thing that matters. Show me a good loser in professional sports, and I’ll show you an idiot. Show me a sportsman, and I’ll show you a player I’m looking to trade to Oakland so that he can discuss his salary with that other great sportsman, Charley Finley.

I believe in rules. (Sure I do. If there weren’t any rules, how could you break them?) I also believe I have a right to test the rules by seeing how far they can be bent. If a man is sliding into second base and the ball goes into center field, what’s the matter with falling all him accidentally so that he can’t get up and go to third? If you get away with it, fine. If you don’t, what have you lost? I don’t call that cheating; I call that heads-up baseball. Win any way you can as long as you can get away with it.

In the olden days, when I was shortstop for the Gas House Gang, I used to file my belt buckle to a sharp edge. We’d get into a tight spot in the game where we needed a strikeout, and I’d go to the mound and monkey around with the ball just enough to put a little nick on it. “It’s on the bottom, buddy,” I’d tell the pitcher as I handed it to him.

I used to do it a lot with Dizzy Dean. If he wanted to leave it on the bottom, he’d throw three-quarters and the ball would sail-vroooom! If he turned it over so that the nick was on top, it would sink. Diz had so much natural ability to begin with that with that kind of an extra edge it was just no contest.

Frankie Frisch, our manager and second-baseman, had his own favorite trick. Frank chewed tobacco. All he had to do was spit in his hand, scoop up a little dirt, and twist the ball in his hand just enough to work a little smear of mud into the seam. Same thing. My nick built up wind resistance on one spot; his smear roughed up a spot along the stitches, and the ball would sail like a bird.

We used to do everything in the old days to try to win, but so did the other clubs. Everybody was looking for an edge. If they got away with it I’d admire them. After the game was over. In a week or two. When Eddie Stanky kicked the bail out of Phil Rizzuto’s hand in the opening game of the 1951 World Series I thought it was the greatest thing I’d ever seen. Not because it was the first time I’d seen ‘it done but because it was my man who was doing it. Before the 1934 World Series began, the St. Louis scouting report warned us that Jo-Jo White of the Detroit Tigers was such a master at it that he would sometimes go all around the bases kicking the bail out of the fielders’ hands. Sure enough, the first chance he had, he kicked the bail out of Frankie Frisch’s glove and practically tore his uniform in half. A couple of innings later, Jo-Jo was on first again. “I got him,” I told Frank.

“No you don’t,” Frisch said. “He’s mine. I’ll get him; you step on him.”

White came into second, and while Frank was rattling the ball against his upper incisors I was dancing a fandango all over his lower chest. I guess Jo-Jo was no aficionado of the Spanish dance because he did nothing at all during the rest of the Series to encourage an encore. Or maybe he just didn’t like the idea of having to make an appointment with his dentist every time he slid into second base.

When my man Stanky does it, he’s helping me to win. When their man White does it, he’s helping them. I can’t be any more explicit about it than to say that you can be my roommate today and if I’m traded tonight to another club I never saw you before if I’m playing against you tomorrow. You are no longer wearing the uniform that has the same name on it that my uniform has, and that makes you my mortal enemy. When the game is over I’ll take you to dinner, you can have my money and we’ll have some fun. Tomorrow, you are my enemy again. T

The Nice Guys Finish Last line came about because of Eddie Stanky too. And wholly by accident. I’m not going to back away from it though. It has got me into Bartlett’s Quotations—page 1059, between John Betjeman and Wystan Hugh Auden-and will be remembered long after I have been forgotten. Just who the hell were Betjeman and Auden anyway?

It came about during batting practice at the Polo Grounds, while I was managing the Dodgers. I was sitting in the dugout with Frank Graham of the old Journal-American, and several other newspapermen, having one of those freewheeling bull sessions. Frankie pointed to Eddie Stanky in the batting cage and said, very quietly, “Leo, what makes you like this fellow so much? Why are you so crazy about this fellow?”

I started by quoting the famous Rickey statement: “He can’t hit, he can’t run, he can’t field, he can’t throw. He can’t do a goddam thing, Frank-but beat you.” He might not have as much ability as some of the other players, I said, but every day you got 100 percent from him and he was trying to give you 125 percent. “Sure, they call him the Brat and the Mobile Muskrat and all of that,” I was saying, and just14 Nice Guys Finish Last at that point, the Giants, led by Mel Ott, began to come out of their dugout to take their warm-up. Without missing a beat, I said, “Take a look at that Number Four there. A nicer guy never drew breath than that man there.” I called off his players’ names as they came marching up the steps behind him, “Walker Cooper, Mize, Marshall, Kerr, Gordon, Thomson. Take a look at them. All nice guys. They’ll finish last. Nice guys. Finish last.”

I said, “They lose a ball game, they go home, they have a nice dinner, they put their heads down on the pillow and go to sleep. Poor Mel Ott, he can’t sleep at night. He wants to win, he’s got a job to do for the owner of the ball club. But that doesn’t concern the players, they’re all getting good money.” I said, “y 011 surround yourself with this type of player, they’re real nice guys, sure—’Howarya, Howarya’—and you’re going to finish down in the cellar with them. Because they think they’re giving you one hundred percent on the ball field and they’re not. Give me some scratching, diving, hungry ballplayers who come to kill you. Now, Stanky’s the nicest gentleman who ever drew breath, but when the bell rings you’re his mortal enemy. That’s the kind of a guy I want playing for me.”

That was the context. To explain why Eddie Stanky was so valuable to me by comparing him to a group of far more talented players who were-in fact-in last place. Frankie Graham did write it up that way. In that respect, Graham was the most remarkable reporter I ever met. He would sit there and never take a note, and then you’d pick up the paper and find yourself quoted word for word. But the other writers who picked it up ran two sentences together to make it sound as if I were saying that you couldn’t be a decent person and succeed.

And so, whenever someone like Ara Parseghian wins a championship you are sure to read, “Ara Parseghian has proved that you can be a nice guy and win.” I’ve seen it a thousand times. They don’t even have to write “Despite what Leo Durocher says” any more.

But, do you know, I don’t think it would have been picked up like that if it hadn’t struck a chord. Because as a general proposition, it’s true. Or are you going to tell me that you’ve never said to yourself, “The trouble with me is I’m too nice. Well, never again.”

That’s what I meant. I know this will come as a shock to a lot of people but I have dined in the homes of the rich and the mighty and I have never once kicked dirt on my hostess. Put me on the ball field, and I’m a different man. If you’re in professional sports, buddy, and you don’t care whether you win or lose, you are going to finish last. Because that’s where those guys finish, they finish last. Last.

I never did anything I didn’t try to beat you at. If I pitch pennies I want to beat you. If I’m spitting at a crack in the sidewalk I want to beat you. I would make the loser’s trip to the opposing dressing room to congratulate the other manager because that was the proper thing to do. But I’m honest enough to say that I didn’t like it. You think I liked it when I had to go to see Mr. Stengel and say, “Congratulations, Casey, you played great”? I’d have liked to stick a knife in his chest and twist it inside him.

I come to play! I come to beat you! I come to kill you! That’s the way Miller Huggins, my first manager, brought me up, and that’s the way it has always beel with me.

I’m just a little smarter than you are, buddy, and so why the hell aren’t you over here congratulating me?

After the Dodgers had lost the final playoff game to San Francisco in 1962, I couldn’t even bring myself to do that. And I wasn’t even the manager, I was only the coach. Still, I should have been the second Dodger over there, right behind Walter Alston. Alvin Dark, the Giants’ manager, was one of my boys. He had played for me and he had been my captain. Many of the Giants players were close friends, and there was Willie Mays, who is as close to being a son as it is possible to be without being the blood of my blood and the flesh of my flesh.

But, damnit, we had gone into the ninth inning leading by two runs. With the ball club we had, we should have run away with the pennant. All right, that’s baseball. I could remember that Jackie Robinson, whom I had been feuding with all year, had been the second Dodger player in our locker room in 1951 after we had beaten them on Bobby Thomson’s home run. I knew Jackie was bleeding inside. I knew he’d rather have been congratulating anybody in the world but me. And still Jackie had come in smiling.

But I sat there without taking off my spikes, and I just couldn’t do it. We had lost with one of the best teams I had ever been associated with. My kind of team. This was the year Maury Wills stole 104 bases and won the Most Valuable Player award. Tommy Davis, who hadn’t broken his ankle yet, had the most incredible year in modern baseball. (Would you believe .346, 230 base hits and 153 rbi?) Plus 27 home runs. Willie Davis, who could outrun the world, had 21 home runs and 85 rbi. Frank Howard was giving us the long ball, 31 home runs and 119 rbi. And good pitching. Don Drysdale was having the best year of 11is life, 25 victories and the Cy Young award. Sandy Koufax had been going even better until he was knocked out by a circulatory blockage in his finger shortly after the All Star game. And still Koufax led the league in Earned Run Average. Ed Roebuck was having a fabulous veal’ in relief.

Seven key players having the best seasons of their career, and we couldn’t shake the Giants.

___________________

I have a philosophy, such as it is, about trouble and adversity. Everything that has ever happened to me has, I believe, happened for the best. I would change nothing. Laraine and I came under fire? It brought us closer together. Chandler picked me out to become his private whipping boy? It only helped him to lose his job and rally people around us. The Giants fans refused to accept me? I didn’t say, “To hell with them; let ’em eat cake.” I stiffened my neck and vowed that, like me or not, I was going to give them a ball club so exciting to watch that they’d come out in spite of me and in spite of themselves.

I had to fight Horace Stoneham to get ‘my kind of team’? That only made the ultimate victory sweeter. And in three years, we won the pennant by tying the Dodgers with the greatest stretch fun in the history of baseball-36 wins in our final 43 games-and ending the playoff series with the most dramatic single moment in the history of sports—Bobby Thomson’s home run.