Read an excerpt from “On Close Reading” by John Guillory

What exactly is “close reading,” and where did the term come from? In On Close Reading, John Guillory takes up two puzzles. First, why did the New Critics—who supposedly made close reading central to literary study—so seldom use the term? And second, why have scholars not been better able to define close reading? In the following excerpt from the book’s preface, Guillory explains why these two puzzles are intertwined.

This small book aims to solve two large puzzles in the history of Anglo-American literary criticism. The first is the question of why the term “close reading” was so infrequently invoked in the decades after its initial mention in I. A. Richards’s Practical Criticism. In fact, the term did not achieve consensus recognition in literary studies until the later 1950s, on the threshold of New Criticism’s decline.

The second puzzle concerns the inability of scholars to define the procedure of close reading in any but the most uncertain terms, usually not much more than is implied by the spatial figure “close.” Sometimes this figure is elucidated by the notion of reading with “attention to the words on the page.” Yet it does not take much research to establish that reading with attention to the words on the page characterizes many practices of reading from antiquity to the present. How can “close reading” name a practice of such scope and duration and yet be seen as emergent during the interwar period of the twentieth century?

These two puzzles are intertwined. The premise of my argument is that the literary critics of the interwar period—both the representatives of “practical criticism” and the American New Critics—were not aiming at first to devise a method of reading at all. Following the lead of T. S. Eliot, these critics—I. A. Richards, F. R. Leavis, Cleanth Brooks, W. K. Wimsatt, and their peers—were most urgently concerned to establish the judgment of literature on more rigorous grounds than had previously obtained in criticism. In the course of forming a conception of literature that would function as the basis for judgment, they developed a corollary technique of reading that confirmed the value of the literary work of art in a universe of new media and mass forms of writing. This technique initially had no name, although it was soon recognized by contemporaries as something new, different from the procedure of the literary historians who dominated the language and literature departments at the time. Our recollection today of the technique’s importance as a methodological innovation suppresses its context in the problem of judgment—or rather, forgets this context. We look back on this moment in the history of the discipline and wonder why the literary critics of the time did not recognize what seems to us now their major achievement.

The marginality of the term “close reading” during the decades after its appearance in Richards’s Practical Criticism was correlated to the difficulty critics had in defining their new practice of reading as a precise sequence of actions. The absence of a definite procedure for close reading contrasts strikingly with the rich aesthetic vocabulary of the New Critics—their development of notions of cultural sensibility (as found in Leavis) and of an “ontology” of the literary work of art (as seen in Brooks, John Crowe Ransom, and René Wellek). It is my contention that the difficulty of defining close reading is an entailment of its nature as technique. Or more precisely, as cultural technique, a very particular kind of methodical human action. All cultural techniques resist definition of the sort that specifies the sequence and components of methodical action. Techniques must be understood as inclusive of the most universal and mundane activities, even the most basic bodily techniques, such as swimming, dancing, riding a bicycle, even tying shoelaces. These cultural techniques can be described, and they can be taught, but they cannot be specified verbally in such a way as to permit their transmission by verbal means alone. Techniques are transmitted rather by demonstration and imitation. The fact of their resistance to precise definition does not contradict their complexity as human actions. Techniques can be described in minimal terms, but they are not necessarily simple. No cultural technique exhibits this paradoxical aspect more than reading, the genus of human action to which close reading belongs as a species, a specialization.

At the core of literary study, then, is a technique with a history, but no precise verbal formula for performance. The technique of close reading can be described but not prescribed. By means of this technique, literary study established its identity as a discipline, despite efforts to repudiate the technique early in its history as mechanical or pseudoscientific, and later to reject it as mired in the social and ideological conditions of its emergence. The history of Anglo-American literary study records the long effort of scholars to come to terms with the muteness of their discipline’s core technique.

In giving an account of this history, I have had occasion to reflect on the question: What is a “technical” term? Literary study is replete with such terms, but for some reason, “close reading” has for the most part fallen out of the discipline’s technical lexicon. The concept of “technique,” which I draw from the work of anthropologists such as Marcel Mauss and employ as a means of understanding modes of reading as transmissible human actions, offers a way forward with this problem. Close reading, as a technique without concept (to invoke Kant’s analogous effort to understand aesthetic perception), constitutes the infrastructure for all disciplinary modes of interpretation, from the formalism of the New Critics to deconstruction, New Historicism, and even, I will argue, what has come to be known as “distant reading.” Finally, I aim to bring the technique of close reading into relation to the long history of writing and reading as cultural techniques, among the most important techniques in the history of human culture, perhaps exceeded only by the gift of Prometheus.

Excerpted from On Close Reading by John Guillory, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2025 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.

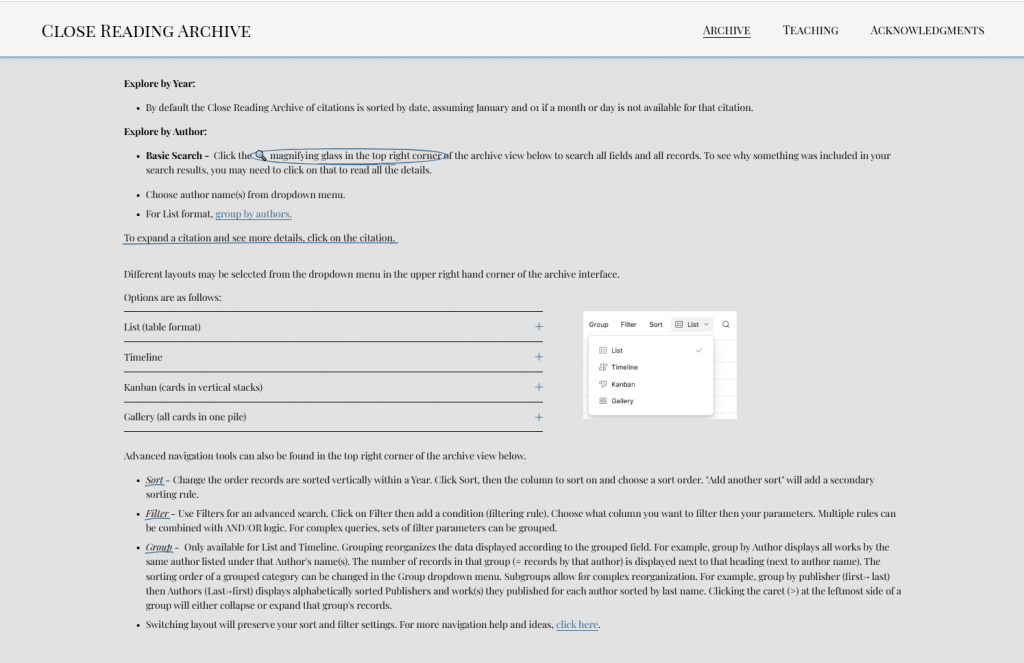

On Close Reading features an annotated bibliography, curated by Scott Newstok, that provides a guide to key documents in the history of close reading along with valuable suggestions for further research. This print bibliography is accompanied by an expanded online resource, the Close Reading Archive:

“As you explore the archive, you might find yourself surprised by the sheer volume of writing on this topic, which has steadily increased since the 1970s, apparently unaffected by shifting disciplinary tides. Patterns begin to emerge: early comments about close reading tend to stem from outside the university, while contemporary scholars increasingly attempt to establish the genealogy of the practice.

Searching permits you to gather your own harvest—whether of one critic’s discussions of “close reading,” an anthology of poems, or even a painting. Perhaps those who survey the archive will assemble their own alternative accounts—so much the better.”—Scott Newstok

John Guillory is the Julius Silver Professor of English at New York University. He is the author of Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon Formation and Professing Criticism: Essays on the Organization of Literary Study, both published by the University of Chicago Press.

Scott Newstok is professor of English and executive director of the Spence Wilson Center for Interdisciplinary Humanities at Rhodes College. He is the author of How to Think like Shakespeare and the editor of several books, including the forthcoming How to Teach Children, a volume of Montaigne’s essays on education.

On Close Reading is available now from our website or from your favorite bookseller. Use the code UCPNEW at checkout on our site for 30% off the book.