Get these inflammatory toponyms before they’re gone

|

|

| Squaw Peak, which overlooks Phoenix, Arizona, drew the attention of Native American activists, who sought to change the name, and place names purists, who resented the governor‘s attempt at renaming. (From the Sunnyslope, Arizona USGS topographic quadrangle map.) | |

An essay by Mark Monmonier, distinguished professor of geography at Syracuse University and the author of From Squaw Tit to Whorehouse Meadow: How Maps Name, Claim, and Inflame.

I‘m surprised few people collect twentieth-century maps, which are more readily available than earlier artifacts, less expensive to acquire, and more varied in content. In contrast to traditional themes like military maps, nautical charts, or a particular mapmaker, the collector of modern maps can easily focus on his or her ancestors, birthplace, travels, hobbies, or occupation. History buffs can concentrate on places prominent in military, diplomatic, industrial, or intellectual history—Gettysburg, Versailles, Thomas Edison‘s Menlo Park (New Jersey), and London‘s Bloomsbury district spring to mind—or on specific types of places, such as battlefields, National Parks, or even disaster sites, which afford intriguing cartographic narratives of affluence, devastation, and recovery. Collectors eager to mix history and design can concentrate on propaganda or transportation maps, while hobbyists fascinated with mapping technology can focus on aerial imagery, engraving techniques, or the effect of computers and computer modeling on map design and content. And young collectors have an excellent chance to see their collections grow in value with rising demand for increasingly rare artifacts.

Place and features names, also called toponyms, make some maps particularly collectable. As I discuss in From Squaw Tit to Whorehouse Meadow, twentieth-century American mapmakers inherited a cultural landscape with inflammatory toponyms like Jap Gulch and Nigger Hill, hidden in plain sight on government topographic maps but difficult to remove because of bureaucratic inertia. While the more offensive racial slurs were erased in the 1960s and 1970s by blanket renaming, politically incorrect or raunchy toponyms become controversial when local residents resist efforts to replace names like Squaw Peak and Whorehouse Meadow, with a recognized yet sullied history.

|

|

| Do the sermons live up to the name? (From the author‘s collection.) | |

War, decolonization, and geopolitical controversy make other maps collectable, especially where names were changed to favor the language, heroes, or whims of a new regime. Remember Bombay and Stalingrad? Geopolitics also accounts for some places having two names, for example, the Sea of Japan (known as the East Sea to Koreans) and the Persian Gulf (known as the Arabian Gulf to the water body‘s non-Iranian neighbors).

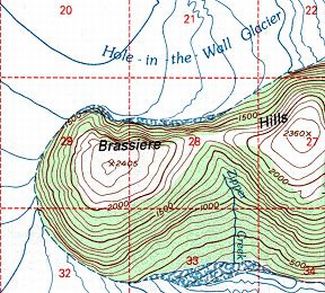

Collecting maps with quirky place names is also fun, especially when snapshots reinforce the apparent absurdity of toponyms like Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, or Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg, a lake in central Massachusetts near the Connecticut border. I took my favorite quirky-map photo in Boring, Maryland, near where I grew up. I‘m not a Methodist, but I often wondered what went on at the Boring United Methodist Church. Another favorite is the U.S. Geological Survey‘s Juneau B-1, Alaska quadrangle sheet, on which a feature named Brassiere Hills makes little sense until you see it on the map. What‘s in a name? More than most of us realize.

Brassiere Hills, as shown on the Juneau B-1, Alaska USGS topographic quadrangle map.

©2006 Mark Monmonier