Baboons in mind

Writing for the May 15 New York Review of Books A.C. Grayling begins his review of several books on primatology with a brief retrospective of the work of Dr. Jane Goodall. Along with several of her contemporaries—Grayling cites paleoanthropologist Louis Leaky, and zoologist Dian Fossey among others—Goodall’s research on primate’s social behavior helped to shed light on the connections between humanity and our nearest living ancestors. And since her groundbreaking study at Tanzania’s Gombe National Park, many other scientists have continued in the same vein, gaining further insights into primates social lives and, in turn, giving us new and deeper insights into our own. As a worthy example Grayling cites Robert M. Seyfarth and Dorothy L. Cheney’s most recent book Baboon Metaphysics: The Evolution of a Social Mind. Grayling writes:

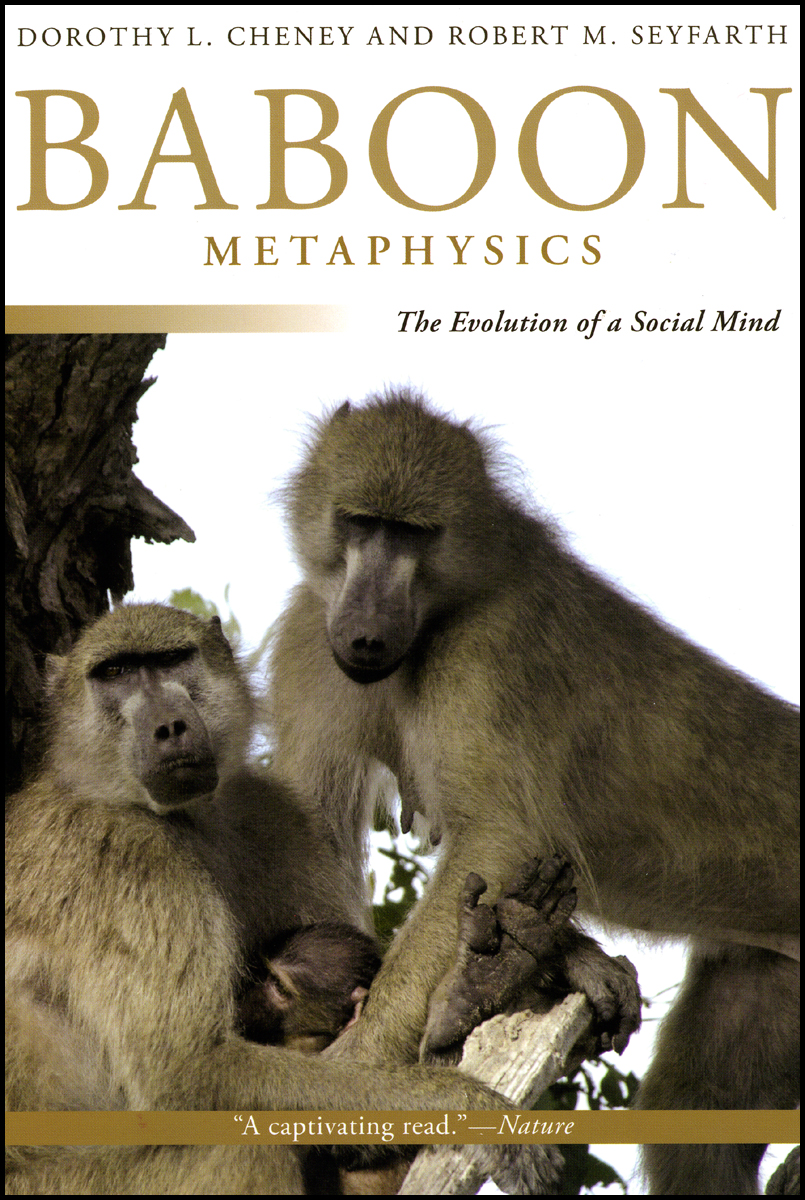

Baboon Metaphysics, by Dorothy Cheney and Robert Seyfarth, shows how far ethology has come since Jane Goodall’s early years at Gombe. An account of Cheney’s and Seyfarth’s field research into the social interactions of baboons, this is an impressive story, not just because of the care that went into the observations and experiments they record, but also in the philosophical sophistication of their thinking about the mental life of baboons.

Cheney and Seyfarth cite a remark from one of Darwin’s notebooks as the starting point for their work: “He who understands baboon would do more towards metaphysics than Locke.” By “baboon” Darwin undoubtedly meant the language, or at least the system of communication, of baboons, and by “metaphysics” he did not mean quite what this word now denotes (namely, inquiry into the fundamental nature of reality) but philosophy in general—especially ethics and the nature and sources of knowledge.… Reconstructing the intention of Darwin’s remark, we see what he had in mind: now that religious explanations will no longer do, the significance and value of things human must be understood by placing mankind squarely in nature, and learning as much as possible from mankind’s closest relatives about how we came to be what we are. Thus understood, Darwinian metaphysics is sociobiology as applied to human beings.

For Cheney and Seyfarth the implication of Darwin’s dictum is that ethological study of monkeys and apes can yield clues to the nature of the mind.…

The review ends on a provocative note:

One thing is clear: whereas human self-importance once placed human beings outside nature, everything that has followed from research of the kind done by Jane Goodall and Cheney and Seyfarth makes it impossible to think in such terms any longer. This point should by now be a mere commonplace; yet there are many millions of people whose faith-based ways of viewing the world lead them to think otherwise.

Read the rest of the review on the New York Review of Books website.

Also read an excerpt from the book.