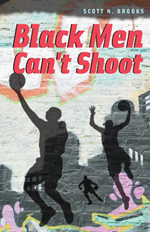

In Defense of Hoop Dreams

On Sunday night, the Los Angeles Lakers bested the Orlando Magic 99 to 86 in Game Five to become the 2009 NBA World Champions. Watching the playoffs, Scott Brooks, author of the new book Black Men Can’t Shoot—a moving coming-of-age story that counters the belief that basketball only exploits kids and lures them into following empty dreams—reflected on LeBron James, whose team, the Cleveland Cavaliers, eventually fell to the Magic in the Eastern Conference Finals. Long considered the poster boy for “hoop dreams,” James was, at the age of 18, the number one pick in the 2003 NBA draft. This season, he was named the league’s Most Valuable Player.

Here, Brooks defends James’s choice to forgo college to join the ranks of professionals and suggests the real problem isn’t black athletes’ hoop dreams but a lack of opportunity and educational inequality.

Watching LeBron James play, I’m reminded of commentary about his skipping college to make his “hoop dreams” a reality (a hoop dream is the unrealistic hope and plan for becoming a professional basketball player, typically held by poor black males and their families).

Some people think that NBA players who leave college after only a year or two or who have skipped college altogether have their priorities misplaced. These young players are considered problematic for their supposed anti-education stance.

Black kids with big dreams are not misguided or pathological for wanting a piece of the pie. We don’t hear the same commentary about puck dreams or diamond dreams or even Wimbledon dreams and the athletes in these sports are often just as young. Sport is not the savior or the curse, the real problem is the dearth of opportunity and options, the invisibility and unknown paths to other desirable careers, and educational inequality.

These young NBA players are actually getting a degree, an NBA degree, and they’ve done a very American thing by jumping to the pros. How are hoop dreams much different than dreams of becoming a lawyer or doctor? Isn’t it American to have dreams of making it, impossible dreams?

Yet, academics generally warn black men against hoop dreaming, arguing that sport exploits them. Mobility is a moving target and blacks take sports too seriously. It is a sport, not a career. Becoming a professional is highly improbable and statistically irrational. Falling short is economic suicide because there are no jobs to fall back on. It teaches no transferable skills. Sport is over-emphasized, given priority over education.

Do people rely upon statistics to choose a career or do they consider job prestige, access, networks, relative realism (what’s realistic for me may not be for you), and rewards? Is an occupation only a good possibility if the chances for earning that occupation are high? Becoming an astronaut is even more rare than an NBA player, yet who discourages kids from pursuing space flight?

As for the argument that athletics doesn’t teach transferable skills, what about black coaches, blacks in sports management, and blacks who go to college (and play) and then go professional “in something besides sports” —NCAA’s new commercial tagline? I’m not suggesting that kids choose. Kids of all races, ethnicities and ages, female and male, should have the freedom to dream and pursue what they want. At the same time, we all need to push for greater equality in outcomes—education, pay and jobs. It’s not an either/or, and most parents understand and push for their kids to do both.

There’s more than direct effects (college ball leads to pro ball) to consider. High school athletes have higher grades than nonathletes (same for college athletes), and athletes tend to be less involved in drugs and less delinquent. Success in sports requires years of practicing and playing in pressure situations. This has latent effects, too. Women athletes laud sports for leveling the playing field, empowering them physically and mentally, and giving them opportunities to achieve. Inner-city boys also claim that sports keep them off the corners, out of gangs, and out of trouble.

Last, a discussion of hoop dreams as either good or bad is trite and does the proverbial “blaming the victim.” Blacks value and encourage schooling. Blacks have sought for and pushed education for many moons—slaves were beaten for reading, and blacks later fought against segregated and unequal schools.

Hoop dreams are not the creation of poor folks. Blacks’ access to playing collegiate and professional basketball cannot be taken for granted. White franchise owners, college administrators and coaches gave opportunities to black athletes with at least two goals in mind: winning and increasing profit. Black males were actively recruited in the 1960s. It was believed that they could make a big difference and this was confirmed when the famed all-black starting five of Texas Western beat Adolph Rupp’s Kentucky white dynasty. Professional teams changed their informal and formal rules, drafted black players, and the game changed quickly. The access to college and a high paying job possibility opened up, creating the hoop dream.

LeBron James, the NBA’s Most Valuable Player for the 2008-09 season and the youngest athlete to be awarded the distinction, ultimately fell short on his quest to earn his first NBA championship. But in only five years, he has ascended to the top of his profession and is arguably the best player in the world. He spent countless hours in basketball gyms and corporate meetings. He has been inspired by Magic Johnson and Michael Jordan and aspires to be more than just a basketball player—he hosted Warren Buffett and Bill Gates this past summer at the pre-Olympic exhibition games in Las Vegas. LeBron James has clearly gained a first rate education in five years and someday may yet earn his PhD in Hardwood—a championship ring.

Read more about Brooks’s book and check out an excerpt from Black Men Can’t Shoot.