The modern afterlives of the bodies in the bog

According to Wikipedia, recorded discoveries of bog bodies—human bodies which have been found remarkably preserved by the unique conditions of the sphagnum bogs in which they are found—go back as far as the 18th century. The mystery surrounding the significance of these bodies and the nature of their demise has for centuries provoked a macabre fascination in the public mind, but until the mid-twentieth century, no one even knew how long the bodies had lain in their muddy graves. As Philip Hoare notes in a recent book review in the Telegraph, it was not until Danish archaeologist PV Glob’s 1969 book The Bog People, that many of these bodies were revealed to be human sacrifices dating back to the early iron age. As Hoare writes “sentenced to death for worldly crimes but slain to propitiate the terrible deities, they were strangled with leather nooses or were pinned face down with wooden struts to drown in the mud.”

Hoare continues:

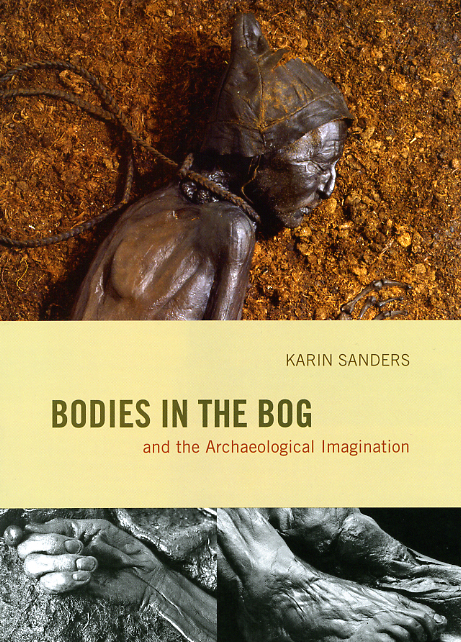

As a young girl in Copenhagen, Karin Sanders, [author of the new book on the subject Bodies in the Bog and the Archaeological Imagination], was also a fan of Glob’s book. But hers is a decidedly post-modern account, one which seeks to show how the bog bodies took their place in our culture, out of theirs, ‘estranged from us even as they mirror us’. She deftly teases out the paradoxes: born of neither land nor water but something in between, the bodies are an uncanny link between the pagan beliefs that prompted their deaths and our own supposedly rational world.

Demonstrating the profound impact these discoveries have made on modern western society, Sanders shows how these eerily preserved remains came alive in art and science as material metaphors for such concepts as trauma, nostalgia, and identity. Sigmund Freud, Joseph Beuys, Serge Vandercam, Seamus Heaney, and other major figures have used them to reconsider fundamental philosophical, literary, aesthetic, and scientific concerns. Sanders contends that the power of bog bodies to provoke such a wide range of responses is rooted in their unique status as both archeological artifacts and human beings. They emerge as corporeal time capsules that transcend archaeology to challenge our assumptions about what we can know about the past.

To find out more read the complete review in the Telegraph.