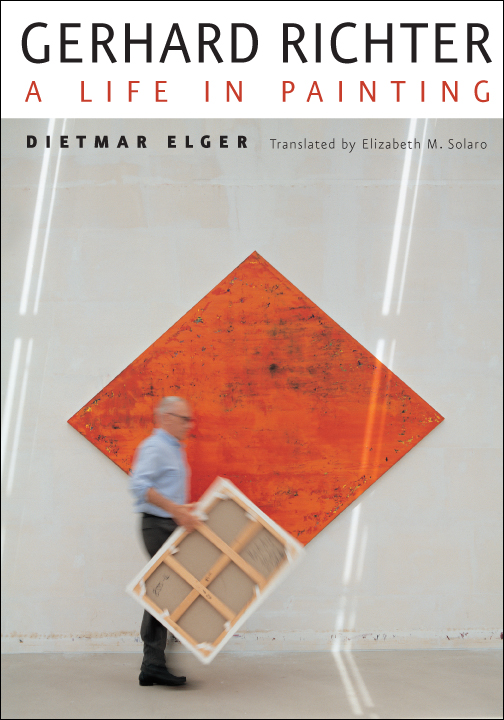

Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting

Gerhard Richter has been known in the United States for some time, especially for the photo-paintings he made during the 1960s that rely on images culled from mass media and pop culture. But as demonstrated by the successful retrospective of his work on display at the MoMA in 2001, Richter’s oeuvre incorporates a highly diverse stylistic range—from the muted tones of the “blurred figurative paintings” produced in the 60s, to the “seductive abstract paintings” of his later work—and has since attracted much attention from audiences and critics alike. Yet despite the artist’s popularity there has been no definitive biographical account of his life, until now.

As a recent review that ran in the February 11th edition of the Financial Times notes with his new book Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting Dietmar Elger offers for the first time insight into this fascinating artist’s life and work. From the review:

Among the many triumphs of Dietmar Elger’s landmark first biography of the artist, Gerhard Richter: A Life in Painting, written with full access to his archives, is to show how Richter’s apparently neutral tones are part of a long, complicated fight against traditional German emotionalism. Born in Dresden a year before the Nazis came to power, Richter had, by the time he fled west to Düsseldorf in 1961, lived under two totalitarian regimes and was passionate above all in his non-commitment to any ideals or absolutes. Hence his refusal to adhere to a single style, alternating figuration, gestural abstraction and geometric minimalism with equal virtuosity.

Yet Elger illustrates from the start that none of Richter’s early subjects, picked from newspaper or family snapshots, was random or innocent: “Onkel Rudi” (killed in the war), “Tante Marianne” (exterminated by the Nazis), “Frau Marlow” (murdered with a poisoned praline), “Teresa Andeska” (a refugee from east to west Germany) are all sinisterly banal images carrying hidden narratives of trauma and tragedy.

Continue reading on the Financial Times website or read this excerpt from the book.