Arthur Koestler’s Dialogue with Death

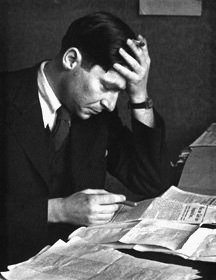

Yesterday marked the twenty-eighth anniversary of the death of Arthur Koestler (1905-83), one of the twentieth century’s more complicated—and controversial—figures: a former Communist Party member and anti-totalitarian scribe; a university dropout, born in Budapest to a mother who was once a patient of Freud, who later renounced his citizenship; a pioneer of science studies with an intrepid interest in the paranormal; and a man frequently preoccupied with death and uncertainty who committed suicide.

Among his numerous biographies, novels, and essays is the work Dialogue with Death: The Journal of a Prisoner of the Fascists in the Spanish Civil War, which chronicles the fall of Málaga in 1937, when Koestler was a German exile writing for a British newspaper. Arrested by Nationalist forces, Koestler spent the next three months in a prison cell in Seville, watching fellow prisoners meet their execution without notice and living in constant fear that his life could end at any moment.

The result is a mix of Doestoevskian insight and journalistic observation. Part journal and part reconstruction, Dialogue with Death is Koestler’s conversation with himself, filled with moments of eerily “Olympian calm” and “colorless disappointment.” Koestler reads Nerval, Bunin, Stevenson, Tolstoy, Plato, St. Simeon, and others, speaks broken Spanish, and considers the anniversary of the Republic, all while ripping strips off of his shirt to stuff into his ears so as not to hear the cries of those shot during the night.

But the candor and extreme self-analysis that carry through this type of experience can often alter perspective. What kind of narrative journalist is Koestler? And what type of biographical writing does the book become? In his Introduction to the new University of Chicago Press edition, Louis Menand makes mention of one salient fact:

There is no reason to doubt anything in the account Koestler gives in Dialogue with Death of his arrest and his ninety-four days in captivity, but there is one major elision. As he made clear in the preface he wrote for the 1967 reprinting of the book, contrary to what William Randolph Heart, the fifty-six MPs, and the League of Nations may have believed, Koestler was not really a journalist when he went to Spain. He was exactly what Franco suspected him of being: a Communist agent. And so he genuinely was, for those three months, at every moment on the verge of being shot. Oddly, this elision (or evasion) is what gives this nonfiction book a kind of literary permanence.

It’s just this sort of detail that makes Koestler the memoir writer as complicated as Koestler the man. As Menand continues:

It is not likely that Koestler was embarrassed about his Communist past. He would write openly about it just a few years later, in The God that Failed; and, in any case, he seems a man who was embarrassed by nothing. He must have seen that the reasons for finding himself in the situation he describes in Dialogue with Death are not important. Between 1933 and 1945, millions of Europeans, the grand and the ordinary, the infamous and the insignificant, found themselves confronted with the knock on the door, with an imminent threat of annihilation. Dialogue with Death is the story of a man who escaped, and only by a hair, his own knock on the door.