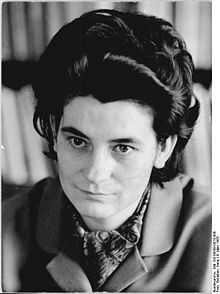

Christa Wolf (1929-2011)

Sad news from Berlin: the passing of critic, novelist, and essayist Christa Wolf. Long credited for helping to establish a distinctive East German literary voice, Wolf was the author of numerous works, including Divided Heaven, The Quest for Christa T., Patterns of Childhood, Cassandra, Medea, On the Way to Taboo, and Accident: A Day’s News. Though much of Wolf’s work engaged with issues of feminism, self-reflexivity, societal pressures, and German fascism, it was her quest for “subjective authenticity” that helped to position her literary output in vital proximity to the social and political issues of her time. In 2002, Wolf was awarded the inaugural German Book Prize for her lifetime achievement.

In her 1994 lecture “Parting from Phantoms: On Germany,” extracted here, Wolf reflects on Germany’s reckoning with its history five years after reunification. Along the way, she describes confronting “a compromising phase in my past” and the uproar that ensued when she revealed that she had worked as an informal collaborator for the East German secret police between 1959 and 1962. “Parting from Phantoms: On Germany” appears in full in Christa Wolf’s Parting from Phantoms: Selected Writings, 1990-1994, published by the University of Chicago Press.

Everything about Germany has been said. I make this claim after wearily pushing aside the stacks of recently published books, the piles of fresh newspaper articles that I have read, skimmed, or left unread. What a giant gruel Germans have been cooking up, talking and writing and analyzing and arguing and polemicizing and pontificating and lamenting, even satirizing themselves and Germany, in the past four years. We have stirred this gruel ourselves, put the pot on the fire, watched it simmer, bubble, sizzle, boil over; we have tasted it, eaten it up like good little children. But the gruel cannot be consumed, nor can it be held in check any longer. It is spilling over the stove and kitchen, out from the messy house onto the road, onto all the streets of our German cities, apparently bringing no nourishment to the homeless Germans who huddle there. And if we well-housed Germans want to be honest—and what do Germans today want more urgently than to be honest!—we must admit that we no longer like the taste of this German millet gruel. We are sick of it. We are fed up with it.

“No!” cries the German Suppenkaspar, the Boy Who Won’t Eat His Soup, who along with his friend Struwwelpeter is just this year celebrating his 150th birthday in blooming health (that is, their story is still being printed in great numbers): “O take the beastly soup away / I won’t eat any soup today!”‘ The question arises how a child raised to be antiauthoritarian can be forced to eat up the soup he has cooked himself, to swallow something he doesn’t like….

Where am I headed? I am searching for a name for a feeling. In Santa Monica, I confronted a compromising phase in my past. I learned how difficult it can be to face the past honestly and adequately when, in Germany, “overcoming the past” on the public level usually takes the form of a chronicle of scandals or a mere skimming of documents—documents that reduce people’s personal histories to simple patterns of yes or no, black or white, guilty or innocent, and provide no information beyond that. I thought then and still think that this credulous faith in files is possible only in Germany. I shall not forget, nor do I want to forget, the physical sensation of being replaced, piece by piece and limb by limb, by another person who was built to suit the media and seeing an empty place arise at the spot where I “really” was. It was an eerie sensation. I then found words for my eerie feeling: the disappearance of reality.

“Unreality” is a word Thomas Mann applied to Germany in 1934, when he was already abroad but not yet in exile. He spoke of the return to unreality. The phrase struck me and preoccupied me deeply. I would often travel up to Mann’s house in Pacific Palisades and go down Amalfi Drive, where he used to walk almost daily when he was writing Doctor Faustus, that awe-inspiring self-confrontation of the German intelligentsia in their failure against fascism. Cautioning myself inwardly not to make pat comparisons, I wondered, Have we Germans now come together in a polity that at last is proof against the temptation to think “tragically, mythically, heroically” the kind of thinking Mann attributed in 1934 to the dear compatriots of his who had succumbed to German myth? Aren’t we now thinking “economically,” “politically”—that is, realistically—at last, in what Mann said was not the German way? Yes, if thinking economically means thinking that the maximization of profit is the highest of all values and if thinking politically means putting the interests of one’s own party above everything else.

Am I being unjust? Partisan? Four and a half years of German unity, and myths and legends abound—some circulated intentionally, some necessarily arising from the way German unity is being pursued. The large-scale attempt to reduce the GDR to the status of an “unconstitutional state,” to assign it to the realm of evil and thus to block historical thinking about it, has proved useful in the equally large-scale title challenges and mass expropriation of the property of GDR citizens. But above all it has helped hide the fact—from our West German fellow citizens, among others—that history is once again sailing in the direction favored by those who have enough clout to determine which way the wind blows. . . .

Where am I headed? I think that in East and West Germany it is time to part from the phantom that each was to the other for so long and thus to part from the phantom of our own land, too. Get down to business, Germany! And why not? We know what happens to denied, repressed reality: it disappears into the blind spot in our consciousness, where it engulfs activity and creativity and generates myths, aggressiveness, delusion. The spreading sense of emptiness and disappointment also produces social maladies and anomalies in which groups of young people “suddenly” drop out of civilization, cancel what seemed abiding social con-tracts, and turn into young zombies without com-passion, even for themselves. At a secondhand bookstore in Santa Monica, I found a story by Friedrich Torberg: “Mein ist die Rache” (Vengeance is mine). The author describes the sadistic practices of a concentration-camp commandant in 1943 who drives a group of Jewish prisoners to commit suicide one after another. It is almost unbearable to read. One reader, apparently an emigre German Jew, added some bitter marginal notes after the war. On the last page this reader penciled in, “America is full of Jews who love Germany and long for it.”

The night after I read this book, a question occurred to me that has stayed on my mind ever since and that I want to pass on to you: What would we all give, each one of us, each individual German, for this not to have happened? It’s a “pan-German” question. Perhaps we will know something more about ourselves if each one of us tries to answer it individually, as honestly and above all as concretely as possible. And doesn’t it lead to three other questions that are worrying us: What was? What remains? What will be?

An English clergyman told us recently that the Germans must make up their minds about themselves, must learn to affirm themselves and the positive sides of their history; otherwise the young people would drift farther and farther away. My family thought about what we Germans could be proud of, what we have that is particularly good, and my fourteen-year-old grandson, who had just spent two weeks in the United States, said, “The bread we bake in Germany.” We laughed, and the more I thought about it, the more I was satisfied with that answer. Bread as an ancient symbol and as everyday concreteness, as the food par excellence, a sensual pleasure you never tire of, simple and at the same time delicious. It fills you, it has aroma, it has flavor, and with its color and manifold shapes it is also a feast for the eyes. Along with wine, it stimulates conversation, friendship, hospitality. What I would like to see—and it’s already happening—are Germans from different points of the compass working together, developing projects, and then sitting down around the table to talk, even to argue, and to eat, to eat in common, the soup they have cooked for themselves. To set on the table the bread they have brought from their various regions, offering it to each other and sharing it gladly and generously.

Translated by Jan van Heurck

Lecture given at the Dresden Staatsoper as part of the “Dresden Lectures” series, February 27, 1994. This translation (first published in PMLA, May 1996) ©1996 by the University of Chicago; all rights reserved.