April’s free ebook: Alice Kaplan’s French Lessons

In 2009, writer and former freelance journalist Ben Yagoda published Memoir: A History. Amid praise for the book is this tidy distillation of its reach by New York Times critic Judith Shulevitz:

[Yagoda] begins with Julius Caesar’s descriptions of the Gallic Wars and proceeds book by book to the present. He gives us the greats—St. Augustine and Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Benjamin Franklin and Frederick Douglass and Helen Keller—but also a 17th-century spiritualizing grifter named Clarkson who preached and seduced his way through England’s radical sects; Mary Jemison of Pennsylvania, whose wildly popular “as told to” reconfigured the classic Indian-captivity narrative into an early-19th-century “Dances With Wolves” (she chose to stay with the Indians); and other figures from what Preston Sturges once called the “cockeyed caravan” of life.

—————————-

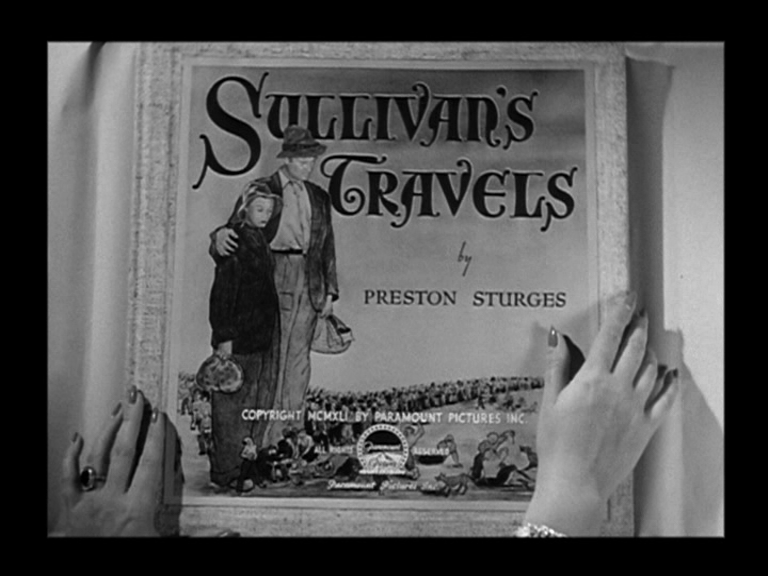

The Sturges quotation is from the movie Sullivan’s Travels, a 1941 Hollywood satire that later served as the inspiration for Joel and Ethan Coen’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? (the Coen Brothers film takes its name from Sturges’s picture-within-a-picture). In it, Sullivan bemoans the (often comic) failures of the would-be socially conscious film he aspires to make, before acknowledging that comedy is really what opens the common man’s heart:

“There’s a lot to be said for making people laugh. Did you know that’s all some people have? It isn’t much … but it’s better than nothing in this cockeyed caravan.”

—————————-

All that said, Alice Kaplan’s French Lessons: A Memoir is the high-soprano’d oboe, delivering its mid-timbered range somewhere in that caravan’s human pageant. The oboe, after all, is French (prior to 1770, it was called the hautbois). Except Kaplan doesn’t mix her metaphors. She will make you laugh, though, in the same eloquent, honest, insightful tone that made her book a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. You can download your gratis copy of French Lessons all April long, as part of our montly free ebook program. All of this, of course, comes on the heels of Kaplan’s latest nonfiction memoir Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag, and Angela Davis (just released today!), which has already accrued rave reviews in Salon, Slate, Publishers Weekly, and the Christian Science Monitor (where it was heralded as the “Number 1” nonfiction book to watch for this spring).

Come for French Lessons; stay for the tour-de-force cultural history.

Brilliantly uniting the personal and the critical, French Lessons is a powerful autobiographical experiment. It tells the story of an American woman escaping into the French language and of a scholar and teacher coming to grips with her history of learning. Kaplan begins with a distinctly American quest for an imaginary France of the intelligence. But soon her infatuation with all things French comes up against the dark, unimagined recesses of French political and cultural life.

The daughter of a Jewish lawyer who prosecuted Nazi war criminals at Nuremburg, Kaplan grew up in the 1960s in the Midwest. After her father’s death when she was seven, French became her way of “leaving home” and finding herself in another language and culture. In spare, midwestern prose, by turns intimate and wry, Kaplan describes how, as a student in a Swiss boarding school and later in a junior year abroad in Bordeaux, she passionately sought the French “r,” attentively honed her accent, and learned the idioms of her French lover.

When, as a graduate student, her passion for French culture turned to the elegance and sophistication of its intellectual life, she found herself drawn to the language and style of the novelist Louis-Ferdinand Celine. At the same time she was repulsed by his anti-Semitism. At Yale in the late 70s, during the heyday of deconstruction she chose to transgress its apolitical purity and work on a subject “that made history impossible to ignore:” French fascist intellectuals. Kaplan’s discussion of the “de Man affair” — the discovery that her brilliant and charismatic Yale professor had written compromising articles for the pro-Nazi Belgian press—and her personal account of the paradoxes of deconstruction are among the most compelling available on this subject.

French Lessons belongs in the company of Sartre’s Words and the memoirs of Nathalie Sarraute, Annie Ernaux, and Eva Hoffman. No book so engrossingly conveys both the excitement of learning and the moral dilemmas of the intellectual life.