UCP Best of 2012 Staff Picks

To catch the wave of year-end lists and Best of the Best citations, we thought to extend our reach beyond the books we publish here at the Press, and ask some of our scholarly tastemakers the works they’d endorse as most praiseworthy in 2012. Not every pick is new and you’ll see some selections here that may not flit across the landscape of other favorites lists—but we’ll be posting the books that made our radar blink all week long, with salutations to the authors, ideas, and publishers (large and small) that keep us coming back for more.

***

Today, we’re off and running with picks from Carol Fisher Saller, our assistant managing editor of manuscript editing at the Press, author of The Subversive Copy Editor: Advice from Chicago (Or, How to Negotiate Good Relationships with Your Writers, Your Colleagues, and Yourself), and editor of The Chicago Manual of Style Online’s Q & A + Rodney Powell, our assistant editor acquiring in film and cinema studies and all-around movie guru:

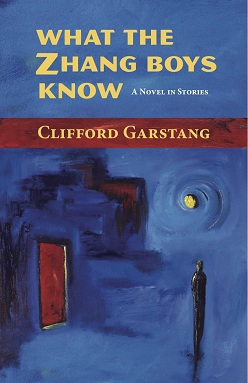

What the Zhang Boys Know, by Clifford Garstang (Press 53, 2012), is a tender look at the residents of the Nanking Mansions condos in the unevenly gentrifying Chinatown of Washington, DC. The boys are the small children of a recent widower, Zhang Feng-qi, and what they don’t know is equally to the point, as the novel’s interwoven short stories take us behind the condo doors of Feng-qi, a gay couple and their little dogs, a sculptor, a desperate and penniless young woman, and others, both to see what the other residents can’t and to view developments through yet another individual’s eyes. Garstang’s forte is the short story—most of these first appeared in literary journals—and this is his second novel in stories. His first, In an Uncharted Country (Press 53, 2009), is every bit as affecting. —Carol Fisher Saller

What the Zhang Boys Know, by Clifford Garstang (Press 53, 2012), is a tender look at the residents of the Nanking Mansions condos in the unevenly gentrifying Chinatown of Washington, DC. The boys are the small children of a recent widower, Zhang Feng-qi, and what they don’t know is equally to the point, as the novel’s interwoven short stories take us behind the condo doors of Feng-qi, a gay couple and their little dogs, a sculptor, a desperate and penniless young woman, and others, both to see what the other residents can’t and to view developments through yet another individual’s eyes. Garstang’s forte is the short story—most of these first appeared in literary journals—and this is his second novel in stories. His first, In an Uncharted Country (Press 53, 2009), is every bit as affecting. —Carol Fisher Saller

I like to circle around subjects over an extended period of time, so it’s not surprising that my favorite book of 2012, Kazan on Directing, was first published in 2009 (the centenary of Kazan’s birth). It includes excerpts from his notebooks, personal journals, and correspondence, as well as other texts, both published and unpublished—a fascinating combination of detailed comments about individual projects and general ruminations about the art of directing for both stage and screen. Go to the chapter on Death of a Salesman (Kazan’s favorite among all the plays he directed) and be engrossed by his analysis of that great work, taken from a notebook entry and script notes. Then go on to a letter he wrote to the four principal actors several months into the run after he attended a performance and found them coasting. I think you’ll be hooked, and ready to investigate the fascinating relationship with Tennessee Williams on four plays and two films—and I haven’t even mentioned the memorable collaborations with Marlon Brando from A Streetcar Named Desire to On the Waterfront. Elia Kazan, whatever his failings, was a major American artist, and Kazan on Directing helps us understand why that is so. —Rodney Powell

I like to circle around subjects over an extended period of time, so it’s not surprising that my favorite book of 2012, Kazan on Directing, was first published in 2009 (the centenary of Kazan’s birth). It includes excerpts from his notebooks, personal journals, and correspondence, as well as other texts, both published and unpublished—a fascinating combination of detailed comments about individual projects and general ruminations about the art of directing for both stage and screen. Go to the chapter on Death of a Salesman (Kazan’s favorite among all the plays he directed) and be engrossed by his analysis of that great work, taken from a notebook entry and script notes. Then go on to a letter he wrote to the four principal actors several months into the run after he attended a performance and found them coasting. I think you’ll be hooked, and ready to investigate the fascinating relationship with Tennessee Williams on four plays and two films—and I haven’t even mentioned the memorable collaborations with Marlon Brando from A Streetcar Named Desire to On the Waterfront. Elia Kazan, whatever his failings, was a major American artist, and Kazan on Directing helps us understand why that is so. —Rodney Powell

Cheers to holiday reading—stay tuned for more!