Neil Verma and War of the Worlds

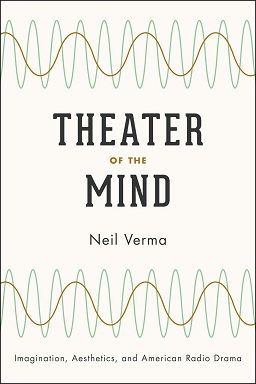

Neil Verma’s work examines idiosyncratic and affective spaces in media history, often those whose eccentricity hinges on particularly interdisciplinary cultural turns. In Theater of the Mind: Imagination, Aesthetics, and American Radio Drama, Verma engages with an archive of over six-thousand radio play recordings—including those penned by Norman Corwin, Wyllis Cooper, and Lucille Fletcher—in order to build a case for the radio drama as one of the most defining forms of mid-twentieth-century genre fiction.

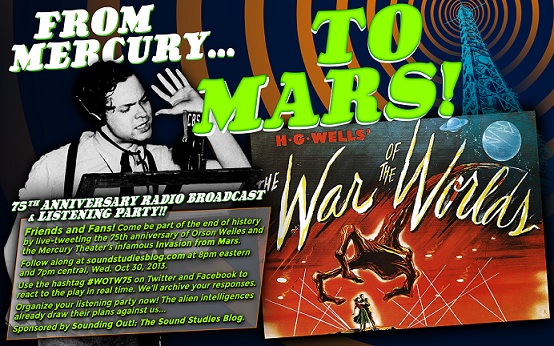

Most recently, Verma has been curating a series of web-based essays on the radio plays of Orson Welles at the Sound Studies blog, which will run until January 2014.

October 30, 2013, marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of “The War of the Worlds,” initially aired by Welles as an episode of The Mercury Theatre on the Air. To commemorate this, Verma will deliver a lecture and slideshow at the Music Box’s 35mm screening of Byron Haskin’s film War of the Worlds (1953) on October 27th and again at an airing of Welles’s original broadcast at Doc Films on October 29th.

On top of this, Verma will helm a nationwide (!) stream and response via social media (hashtag: #WOTW75) to the original recording, in addition to a re-airing and documentary broadcast out of WHRW (Binghampon, NY), on October 30th.

***

And, finally, in anticipation of these upcoming events, we fielded a brief Q & A with the author:

How does someone your age become interested in old-time radio?

It might be because I learn better by listening than by reading. My earliest memory of being in a classroom is from a second-grade class in which our teacher would read to us each afternoon. I have a very clear memory of her reading Mordecai Richler’s Jacob Two-Two Meets the Hooded Fang. The great radio writer Norman Corwin once told me that he would run into people on flights who remembered detailed sequences from his radio plays, sometimes thirty or forty years after they aired.

I got in to classic radio thanks to a series of dusty editions of The Shadow released by Radio Spirits, which I stumbled upon in the lower shelves of a local bookstore ten years ago. I was amazed to discover that no one had really written an intensive study of the form that theorizes how radio plays work. For two decades or so in the 20th century, radio drama was arguably the most consumed form of fiction in the United States, and I was fascinated by the challenge of writing something that could explain its dynamics from an aesthetic point of view. It just became an obsession from there, like most academic projects.

I don’t think there’s anything strange about getting interested in radio plays, any more than there is getting into Giotto or 18th century textiles. There’s just something compelling about these broadcasts. And many people retain a cultural memory of classic radio today. When I first met my wife and told her what I studied, she replied with the famous line from The Shadow—”Ah, ‘Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men,’ right?” I replied, “Well, I suppose I do.” A terrible line!

What are some of your favorite radio plays or dramas?

My favorite all-around program is Wyllis Cooper’s Quiet Please, a strange fiction series from the late 1940s. For people just getting in to radio, Suspense is a rich and important program. Broadway is my Beat is an interesting case of a crime show; so is Gangbusters. For anthology programs, Studio One and the Columbia Workshop are both ambitious and well crafted. I find Orson Welles’s “A Passenger to Bali” and “Hell on Ice” extremely powerful as individual plays. I think Lucille Fletcher’s plays are very clever, particularly “The Hitch-hiker,” and I like much of what Arch Oboler did on Lights Out. For a limited serial, I Love a Mystery is a great choice. All of Norman Corwin’s plays are fascinating.

When did you first hear about War of the Worlds, and which did you discover first: the book, the broadcast, or the film?

I’m sure I saw the 1953 version on late night TV some time as a child. But the thing about the WOTW episode is that everyone has heard about it before they actually heard it. It’s kind of a folk tale. Even if you haven’t heard it, you feel like you did—it’s part of the texture of modern culture.

I’m not sure when I first heard the radio play, but I remember that I did most of my listening to Welles’s plays during a summer I spent in Vancouver in 2005. It was interesting to listen to it along with hundreds of his other radio plays—versions of The 39 Steps, A Tale of Two Cities, Dracula, Heart of Darkness, It Happened One Night, Rebecca, The Glass Key, and many more.

What fascinated you about WOTW the most?

Everything. The opening monologue; the way the first act is structured like a newscast; the performance of Frank Readick as Carl Phillips; the dive-bombing sequence; the character of the stranger bent on dominating the future in the second act; the sound of the martian cylinder opening, which was created by Ora Nichols with a cast iron pot and lid.

Above all, the five or six seconds of silence after the end of the first act—the airtime subsequent to the “end of the world.” It’s a fascinating stretch of silence, really one of the great pauses in all auditory artwork of any kind. Most great radio plays cunningly convince you that you are only projecting your own imagination; in this case, given an unmodulated carrier wave, you project a void. There’s an appel du vide quality to that, you’re staring down over a cliff and feeling the urge to jump.

For generations, most writers on WOTW have concentrated on the panic following it, most of them wishing the latter was more serious and widespread than it really was. I think we’ve arrived at a point in history at which people are starting to realize that the play itself is more interesting than the public’s reaction to it.

What do you make of the public outcry after the radio broadcast in 1938? Do you think the broadcast was dishonest?

No one knows for sure, but I think it was all a mistake, one that was blown wildly out of proportion by the press. Only later in life did the principle figures begin to say they planned it all this way. And only a small fraction of the population panicked. People did weird things—fleeing into the night, driving like mad, swearing they could see fires where there were none. Some were treated for shock, and telephone switchboards lit up with complaints. But no one died, had a heart attack, or miscarried, contrary to popular memory.

It was the press, more than anyone else, that created the idea of the panic, and historians and scholars who sustained it. But that’s not to say the myth of the panic ought to be discarded. Far from it. It’s important to recognize what’s behind our own wish to believe in the event. In doing so we learn a lot about our fantasies and anxieties about vulnerability toward mediation.

Theater of the Mind mostly focuses on mid-twentieth-century radio. Do you tune into radio programs of today? Which are your favorites?

Yes, I still love the practice, although nothing exists quite like golden age broadcasts. I’m a fan of work on BBC Four, and have been following many of their CD releases—these days it’s easy to get hold of everything from Tom Stoppard’s radio plays to dramatizations of John Le Carre. Sound artists have been increasingly getting interested in the radio play format, I’m working these days on exciting speculative fiction pieces by Anna Friz and Emmanuel Madan. I’m also getting more interested in podcast formats. I like the monologues in Welcome to Night Vale a lot and I’m a fan of a New York-based radio drama group called The Truth, which I’d recommend to everyone. The podcast is already the future of the radio play.

***

For more information about Verma’s Theater of Mind: Imagination, Aesthetics, and American Radio Drama click here.