University Press Week, World Book Night, and Young Men and Fire

This week marks the second annual University Press Week, which celebrates “the variety of ways that university and academic presses are innovating both in the formats that they publish in and the subject areas in which they find vital research to further excellence in scholarship.” Taking off on last year’s inaugural initiative, #UPWEEK features a variety of endeavors ranging from online panel discussions and a blog tour to events at national and local booksellers, the full schedule of which is accessible at the American Association of University Press’s website.

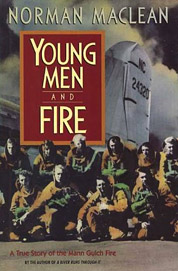

In case you missed it, and to help kick things off, we’re delighted to announce that Norman Maclean’s Young Men and Fire has been selected to participate in World Book Night 2014—the first book published by a university press chosen to do so. In addition to Young Men and Fire, we’re proud to include Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, The Norman Maclean Reader, and Custer’s Last Stand: The Unfinished Manuscript (a Chicago Short) as part of our list in literature and literary studies. The book, which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary, was published posthumously after Maclean’s death in 1990, and its chronicle of the 1949 Mann Gulch forest fire, an event that haunted Maclean for nearly forty years, took home the National Books Critic Circle Award in 1992.

If you haven’t read Norman Maclean (1902–90) before, you’re in for a discovery. In Young Men and Fire, Maclean’s seemingly humble prose belies a story about a calamitous fire and its legacy that epitomizes the human condition—the search for meaning amid monstrous tragedy and mortality and one man’s pursuit of truth as a powerful and multilayered meditation on everything from writing and religion to mystery and justice. Below follows a very brief excerpt, the full version of which can be read at the University of Chicago Press’s Maclean satellite site.

***

The world was getting faster, smaller, and louder, so much faster that for the first time there are random differences among the survivors about how far apart things were. Dodge says it wasn’t until one thousand to fifteen hundred feet after the crew had changed directions that he gave the order for the heavy tools to be dropped. Sallee says it was only two hundred yards, and Rumsey can remember. Whether they had traveled five hundred yards or two hundred yards, the new fire coming up the gulch toward them was coming faster than they had been going. Sallee says, “By the time we dropped our packs and tools the fire was probably not much over a hundred yards behind us, and it seemed to me that it was getting ahead of us both above and below.” If the fire was only a hundred yards behind now it had gained a lot of ground on them since they had reversed directions, and Rumsey says he could never remember going faster in his life than he had for the last five hundred yards.

Dodge testifies that this was the first time he had tried to communicate with his men since rejoining them at the head of the gulch, and he is reported as saying—for the second time—something about “getting out of this death trap.” When asked by the Board of Review if he had explained to the men the danger they were in, he looked at the Board in amazement, as if the Board had never been outside the city limits and wouldn’t know sawdust if they saw it in a pile. It was getting late for talk anyway. What could anybody hear? It roared from behind, below, and across, and the crew, inside it, was shut out from all but a small piece of the outside world.

They had come to the station of the cross where something you want to see and can’t shuts out the sight of everything that otherwise could be seen. Rumsey says again and again what the something was he couldn’t see. “The top of the ridge, the top of the ridge.

“I had noticed that a fire will wear out when it reaches the top of a ridge. I started putting on steam thinking if I could get to the top of the ridge I would be safe.

“I kept thinking the ridge—if I can make it. On the ridge I will be safe… I forgot to mention I could not definitely see the ridge from where we were. We kept running up since it had to be there somewhere. Might be a mile and a half or a hundred feet—I had no idea.”

The survivors say they weren’t panicked, and something like that is probably true. Smokejumpers are selected for being tough, but Dodge’s men were very young and, as he testified, none of them had been on a blowup before and they were getting exhausted and confused. The world roared at them—there was no safe place inside and there was almost no outside. By now they were short of breath from the exertion of their climbing and their lungs were being seared by the heat. A world was coming where no organ of the body had consciousness but the lungs.

Dodge’s order was to throw away just their packs and heavy tools, but to his surprise some of them had already thrown away all their equipment. On the other hand, some of them wouldn’t abandon their heavy tools, even after Dodge’s order. Diettert, one of the most intelligent of the crew, continued carrying both his tools until Rumsey caught up with him, took his shovel, and leaned it against a pine tree. Just a little farther on, Rumsey and Sallee passed the recreation guard, Jim Harrison, who, having been on the fire all afternoon, was now exhausted. He was sitting with his heavy pack on and was making no effort to take it off, and Rumsey and Sallee wondered numbly why he didn’t but no one stopped to suggest he get on his feet or gave him a hand to help him up. It was even too late to pray for him. Afterwards, his ranger wrote his mother and, struggling for something to say that would comfort her, told her that her son always attended mass when he could.

It was way over one hundred degrees. Except for some scattered timber, the slope was mostly hot rock slides and grass dried to hay.

It was becoming a world where thought that could be described as such was done largely by fixations. Thought consisted in repeating over and over something that had been said in a training course or at least by somebody older than you.

Critical distances shortened. It had been a quarter of a mile from where Dodge had rejoined his crew to where he had the crew reverse direction. From there they had gone only five hundred yards at the most before he realized the fire was gaining on them so rapidly that the men should discard whatever was heavy.

The next station of the cross was only seventy-five yards ahead. There they came to the edge of scattered timber with a grassy slope ahead. There they could see what is really not possible to see: the center of a blowup. It is really not possible to see the center of a blowup because the smoke only occasionally lifts, and when it does all that can be seen are pieces, pieces of death flying around looking for you—burning cones, branches circling on wings, a log in flight without a propeller. Below in the bottom of the gulch was a great roar without visible flames but blown with winds on fire. Now, for the first time, they could have seen to the head of the gulch if they had been looking that way. And now, for the first time, to their left the top of the ridge was visible, looking when the smoke parted to be not more than two hundred yards away.

Navon had already left the line and on his own was angling for the top. Having been at Bastogne, he thought he had come to know the deepest of secrets—how death can be avoided—and, as if he did, he had put away his camera. But if he really knew at that moment how death could be avoided, he would have had to know the answers to two questions: How could fires be burning in all directions and be burning right at you? And how could those invisible and present only by a roar all be roaring at you?

***