Q & A with Peggy Shinner

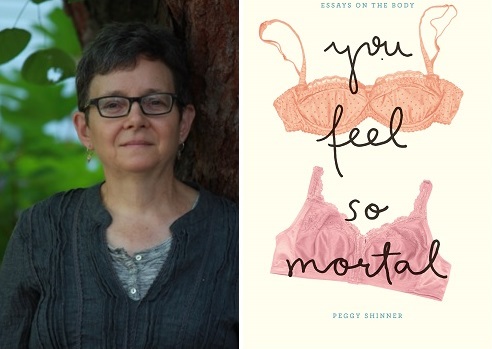

Peggy Shinner is a lifelong Chicagoan and author of the forthcoming collection You Feel So Mortal: Essays on the Body. A Q & A about bodies, the book, and Shinner’s process follows below.

***

What led you to write a collection of essays about the body?

The first piece I wrote was about knives. At the time I was a practicing martial artist, and we trained with them in class. We called them practice knives; they were fake—rubber or wood. “Go get a knife,” the teacher would say. And so there we were, a room full of students stabbing and slashing each other. The purpose, of course, was to learn to defend ourselves against them. But I found the whole thing odd and disconcerting. Here I was learning to stab someone. From knives I went on to autopsies. I’d authorized one for my father, and for a long time after I’d been uncomfortable with that decision. Knives, autopsies. It didn’t take long for me to see that I was on to something, and from there the essays seemed to emerge.

You reveal very personal things about yourself in your essays. How is your collection of essays different from a memoir?

It’s true that I start off with personal material but that’s never what interests me, at least not in and of itself. For a long time, for instance, I’d wanted to write something about posture. I myself have bad posture. But so what? What was I going to say? Poor me, I have bad posture? That doesn’t interest me and I don’t think it would interest anyone else.

What fascinates me is the framework I can build around this material. How do we understand slumping in a historical context? Why did slumping, embodied by the debutante slouch—a posture taken on by women in the early twentieth century—become a form of social rebellion? Why, in some quarters, was slumping seen as an indicator of moral depravity? It’s questions like these that drive the work, and if I can’t always answer them, I can dive in and explore them. I’m interested in that place where my personal experience collides with the larger world.

Martial arts has had a profound influence on your life. Has it also influenced your writing and what you choose to write about?

In a sense, my martial arts practice provided a backdrop for these essays. I wrote most of the book while I was studying and teaching karate, and when you’re punching and kicking on a daily basis you have a heightened awareness of your body. There’s a certain kind of body check-in that you do, conscious and unconscious. As a martial artist, you have a corporeal experience of the world. That awareness undoubtedly filtered into the book. There’s also something about the methodology of the martial arts that translates to writing. Karate is a highly repetitious practice. You do the same techniques over and over again. A hundred backfists in a single class. There’s discipline and there’s drudgery. Your love of the martial arts derives from the dialectic of those two attributes. And I think the same thing is true of writing. It requires a studied discipline, out of which comes both dreariness and delight. Put the comma in, take the comma out, as Flaubert so famously said. This is how you develop a “writer’s callus.”

Objects seem to hold particular weight in your essays. In one, writing about a letter “thrill kill” murderer Nathan Leopold sent to your mother, you say, “The letter was an artifact, like her wallet, wristwatch, keychain, Social Security card, also put away in a drawer—a memento of my mother.” In another you focus on your father’s death certificate, “a document brimming with possibilities.” Can you talk about the importance of these artifacts?

I think about the essays in terms of an archaeological expedition or excavation. And one of the tools is memory; but memory, of course, can only dig up so much, and often incompletely. So these artifacts become stand-ins, things I can turn over and subject to interrogation. The letter, the Social Security card, the death certificate—what can they tell me about my parents, the bodies I came from? I try to squeeze information out of them. Take them apart and perhaps put them back together in a slightly different configuration. Do they fill in the gaps? No. But they allow me to speculate about my parents and myself and our place in the world and perhaps get to know them a little better.

Can you talk about the title of your book You Feel So Mortal?

Well, what is the body but a mass of skin and bone and muscle and sinew and systems. The whole enterprise is tough, amazing, fragile, and transitory. There are so many things, over the course of a lifetime, we do to the body—decorate, alter, arouse, feed, exert, nurse, curse, cut, sew, and abuse it. It’s how we meet and apprehend the world. And then the whole adventure’s over, and we leave it behind. The phrase itself, “you feel so mortal,” came from a line I’ve since discarded in one of essays. The title is what remains.

To read more about You Feel So Mortal, click here.