Carl Zimmer on the Ebolapocalypse

Carl Zimmer is one of our most recognizable—and acclaimed—popular science journalists. Not only have his long-standing New York Times column, “Matter,” and his National Geographic blog, The Loom, helped us to digest everything from the oxytocin in our bloodstream to the genetic roots of mental illness in humans and animals, they also have helped to circulate cutting-edge science and global biological concerns to broad audiences.

One of Zimmer’s areas of journalistic expertise is providing context for the latest research on virology, or, as the back cover of his book A Planet of Viruses explains: “How viruses hold sway over our lives and our biosphere, how viruses helped give rise to the first life-forms, how viruses are producing new diseases, how we can harness viruses for our own ends, and how viruses will continue to control our fate for years to come.”

It shouldn’t come as any surprise, then, that with regard to recent predictions of an Ebolapocalypse Zimmer stands ready to help us interpret and qualify risk with regard to Ebola and the biotech industry’s push for experimental medications and treatments.

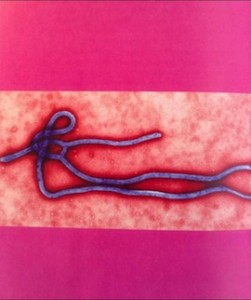

At The Loom, Zimmer shows a strand of the ebola virus as an otherworldly cul-de-sac against a dappled pink light. As he writes, we still have no antiviral treatment for some of our nastiest viruses, including this one, as, “viruses—which cause their own panoply of diseases from the common cold and the flu to AIDS and Ebola—are profoundly different from bacteria, and so they don’t present the same targets for a drug to hit.”

A Planet of Viruses takes this all a step further; in the chapter “Predicting the Next Plague: SARS and Ebola,” Zimmer advocates a cautionary—but not hysterical—approach:

There’s no reason to think that one of these new viruses will wipe out the human race. That may be the impression that movies like The Andromeda Strain give, but the biology of real viruses suggests otherwise. Ebola, for example, is a horrific virus that can cause people to bleed from all their orifices including their eyes. It can sweep from victim to victim, killing almost all its hosts along the way. And yet a typical Ebola outbreak only kills a few dozen people before coming to a halt. The virus is just too good at making people sick, and so it kills victims faster than it can find new ones. Once an Ebola outbreak ends, the virus vanishes for years.

With its profile rising daily, this most recent Ebola outbreak is primed to force us to rethink those assumptions–and to reflect the commingling of key issues at the intersection of biology, technology, and Big Pharma. As an article in today’s New York Times about a possible experimental medication points out, therapeutic treatment of the virus is already plagued by this overlap:

How quickly the drug could be made on a larger scale will depend to some extent on the tobacco company Reynolds American. It owns the facility in Owensboro, Ky., where the drug is made inside the leaves of tobacco plants. David Howard, a spokesman for Reynolds, said it would take several months to scale up.

Regardless of the course, we’ll look to Zimmer to help us digest what this means in our daily lives—whether we’re assembling a list of novels for the Ebolapocalypse like The Millions, or standing in line at CVS for a pre-emptive vaccination.

Read more about A Planet of Viruses here.